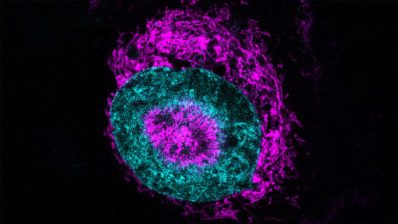

Our own immune system may be our best ally in cancer treatment, and this is something that the scientific community has known and has been studying for a long time. A biological therapy that stimulates the body’s natural defenses to stop or decrease the growth of cancer cells, even destroying them. This is the great potential of immunotherapy and, given its importance, the Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (IMIM) held, on October 30, the 3rd edition of the Optimizing Immunotherapy: New Approaches, Biomarkers, Sequences and Combinations course in the Auditorium of the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB).

Immunotherapy stimulates the body’s natural defenses to stop or decrease the growth of cancer cells, even destroying them

Several researchers and experts in the field shared their latest studies at this annual meeting. Among them were the oncologist and clinical researcher at the Vall de Hebrón Hospital, Guillem Argilés, and the ICREA researcher, Núria López-Bigas, group leader at the Biomedical Genomics group of the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) – formerly at the Research Programme on Biomedical Informatics (GRIB, IMIM-UPF).

Argilés talked about the influence of the human microbiome, that is, the genetic material of our microbiota, on our immune system. On the other hand, López-Bigas focused on the usefulness of genomic data analysis when applying immunotherapies.

The microbiome as a predictor of benefit and toxicity

Our microbiome is made up of different types of microorganisms: from bacteria to protozoa. If we focus on the bacterial microbiome, specifically in the gut microbiome, we can confirm that it not only intervenes in local diseases of the colon, but can also influence the appearance of certain systemic, mental and brain diseases. This relationship of the microbiota with some diseases would be a consequence, in part, of intestinal secretions, which could affect our hormonal homeostasis, even at the cerebral level. And, as Argilés confirms in his presentation, “almost 80% of our immune system is located in our gut, so that there is a close relationship between our microbiota and the body’s natural defense system. Consequently, the local immune responses induced at an intestinal level may end up spreading at the systemic level”.

To better understand this relationship Argilés explains that, using mice treated with immunotherapy and comparing some previously treated with antibiotics with other not treated, they observed the following results:

- Antibacterial treatment and, therefore, the elimination of certain bacteria, considerably decreases the immune response induced by immunotherapy.

- It is the richness of our intestinal microbiota which really facilitates the antitumor immune response.

However, by overstimulating the immune system, toxicity appears as a side effect so that cancer patients with greater immune response and, therefore, those who obtain better results when applying immunotherapy, are also those who suffer the most toxicity.

Almost 80% of our immune system is located in our gut, so that there is a close relationship between our microbiota and the body’s natural defense system.

At the same time, it has been observed that modifying the microbiota of patients can help obtain better results when applying immunotherapy treatment. However, it has been shown that the administration of probiotics is not a solution. In fact, taking probiotics is highly negative in cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy since, in some of them, a reactive response is induced based on a local inflammation — at the level of the intestinal epithelium — that eliminates these probiotics.

So:

- A healthy microbiota promotes a healthy body.

- Anti-microbiota immune responses help maintain a basal activation of our immune system which, in turn, helps promote the efficacy of immunotherapy.

- The manipulation of the microbiota through the administration of probiotics does not improve patients outcome.

How to analyze genomic data in the application of immunotherapy

Exposure to certain external agents leads us to accumulate somatic mutations. However, thanks to cell repair pathways, our body can reverse the vast majority of these genetic errors. Those not repaired become mutations and, depending on the external factor that has induced them (exposure to UV rays, tobacco, DNA replication errors…), they can be classified within a mutational signature or another. Mutational signatures in cancer are the mutation processes that occur in our genetic material that follow a certain pattern.

López-Bigas explained in her talk that the aim of her latest study is to understand what the mutational signature of chemotherapy is, since it is known that this therapeutic technique used in the treatment of cancer induces long-term negative effects, among which we can find secondary neoplasms. These effects are associated with the mutations that cancer patients treated with chemotherapy accumulate in their body.

“Chemotherapy causes 100 times more mutations per month than the natural aging process”

Thus, the main goal of the ICREA researcher is to identify and quantify the mutational signatures induced by chemotherapy. To do this, she and her team have studied patients who, after 2-3 years of receiving chemotherapy treatment, eventually developed metastasis. The advantage of working with these patients is that, since chemotherapy induces different mutations in every single cell — and it would be necessary to carry out an individual cell sequencing in order to study them —, the clonal expansion of metastasis facilitates the analysis of the mutational signatures.

When they finished the study, they observed that many of these mutational signatures were not associated with chemotherapy. However, some mutational patterns were related to certain cancer treatments, such as capecitabine.

It was also found that treatment-related mutations appeared late in time (compared to those related to smoking, for example) and were subclonal (that is to say, they appeared in some cells and as a result of other mutations), as expected.

The combination of immunotherapy with other treatments: the key topic of the day

The novelty of this year’s meeting was the combination of immunotherapy with other treatments, such as chemotherapy, in types of cancer that were not contemplated until now. “In fact, Hans Hammers, one of the speakers, has developed one of the latest advances in kidney cancer”, highlights Joaquim Bellmunt, former IMIM‘s director.