Cancer causes nearly 13% of the total deaths in the world – about 9.6 million people only in 2018.

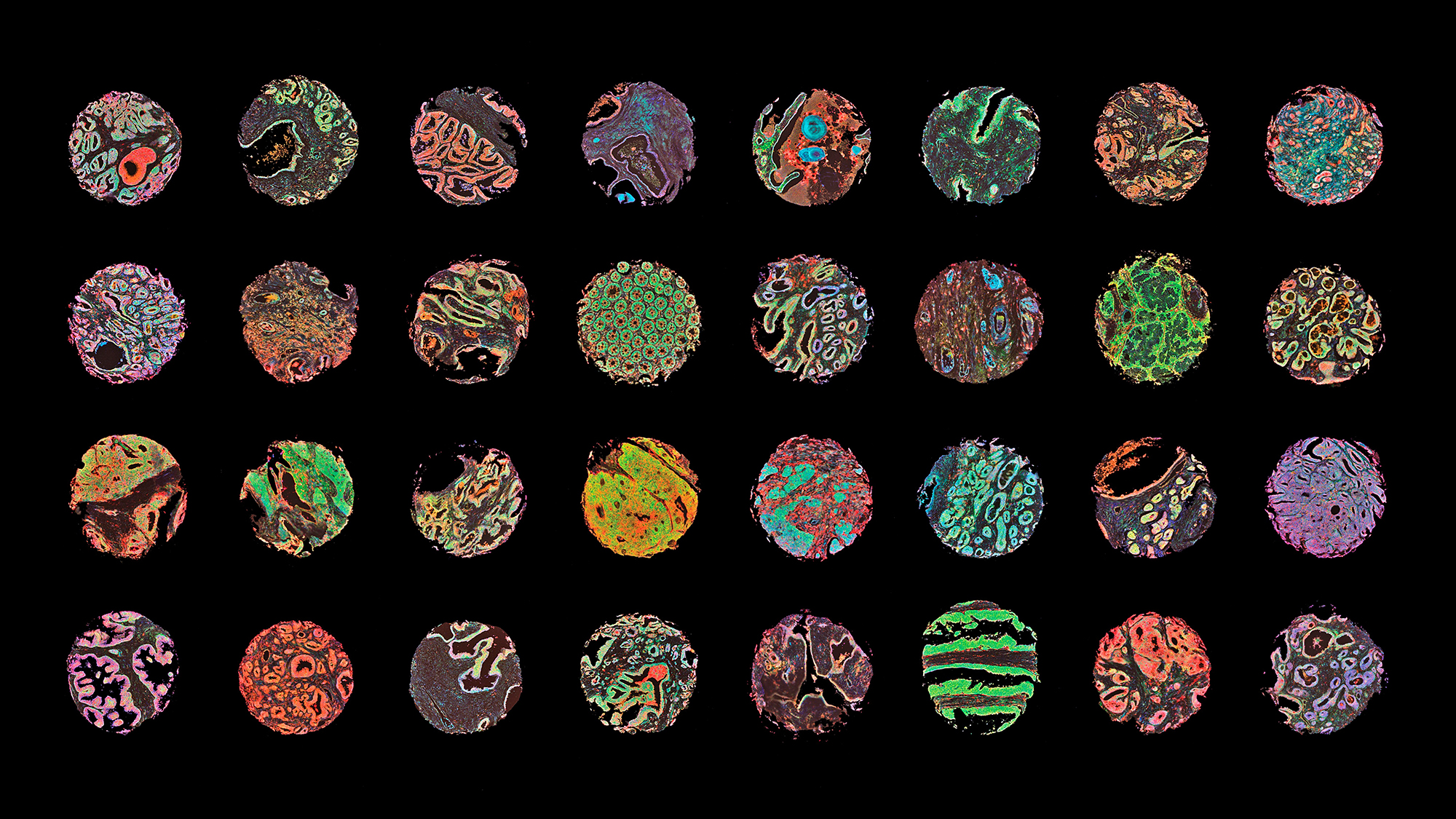

It is often said that it is not just one disease, but several. Not only there are about 100 different types of cancer, according to which tissue they affect, but there are also many different causes that can lead to this disease.

There are two types of genes implied in cancer:

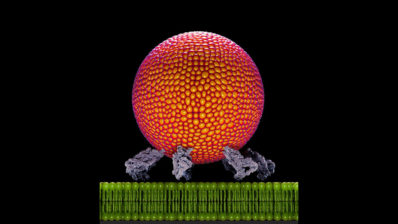

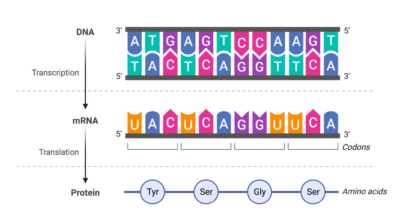

- Oncogenes are those genes that, when expressed more than needed, could cause cancer. In normal conditions these genes are ‘accelerators’: they make the cell advance in its cycle and divide. But if they are hyperactivated, the cell reproduces without control.

- The tumour suppressor genes, on the other hand, are the ‘brakes’ of the cell. They are the genes that under normal conditions regulate the cell division cycle, repair the anomalies of the DNA and, if the cell has an unsolvable problem, kill the cell. Indeed, if there is a defect in the duplication of DNA that cannot be corrected, the tumour suppressor genes stop the cell, leading to apoptosis or programmed cell death. If these genes are mutated, however, the cell is unable to commit suicide for the sake of the organism, and it continues dividing.

Cancer is a condition in which our own cells divide without control: the ‘accelerators’ accelerate too much, and the ‘brakes’ stop working.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are two examples of tumour suppressors involved in breast cancer that in normal conditions participate in DNA repair. If they are mutated, they cannot do their function correctly, and DNA accumulates more and more mutations, which can lead to an uncontrolled growth of the cell and to cancer. Hence, having a mutation in one of these genes implies a higher risk of developing the disease.

Breast cancer is therefore a tumour with a hereditary component, but many others are not. They are just due to the accumulation of mutations during life.

In both cases, though, for a cancer to form there must be several genes mutated in the same cell. This is because the cell has several parallel control systems so that, if one fails, the other can maintain the order. For a cancer to appear, all the control systems must fail at the same time. At first sight this seems very unlikely. But it is not so strange, taking into account that our cells accumulate milions of mutations per day– although most of them don’t have any harmful effects. These mutations can be caused by the environment or by simple errors of the cell’s DNA duplication machinery.

For cancer to appear, all the control systems must fail at the same time.

In summary, cancer is a condition in which our own cells lose control: the ‘accelerators’ accelerate too much, and the ‘brakes’ stop working. Therefore, in order to understand and fight cancer, we need to know how cells work in normal conditions and how and why they lose control.