“The word “vocation” makes students afraid; 12-year-old kids, even 16-year-olds, don’t know what they want to do in the future at all. It is a period of doubt. I would banish the word vocation and tell them to look for their aspirations. We must help them not to discard science too soon, since it can be a very good travel buddy, regardless of what they end up doing in the future. Scientific knowledge will help them be happier”.

This is how Digna Couso, the director of the Research Centre for Scientific and Mathematical Education (CRECIM) in the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), started her presentation at the 100tífiques meeting.

The meeting, which took place in the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB) last january 30th, consisted of a training session for the more than 180 female researchers who would go on to 100 Catalan schools to give science talks on the following February 11, International Day of Women and Girls in Science. In this session, the researchers were provided with the necessary tools to carry out these talks.

The 100tífiques initiative, organized by the Catalan Foundation for Research and Innovation (FCRI) and the Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology (BIST), is already in its second edition, and it aims not only to bring science closer to students, but to do so with a gender and diversity perspective. Science is made by people and these people are very different from each other. Thus, when giving talks and carrying out other outreach activities, it is necessary that this diversity is being well represented, because it’s hard for someone to aspire to be like those he or she does not identify with.

Why do we give science talks to students?

Among the many different questions that promoted the debate throughout the meeting, Couso said: why do we go to give science talks to schools?

On the one hand, the CRECIM director stressed that, rather than trying to improve the scientific literacy of the youth by sharing updated scientific knowledge, what we should do is sharing comprehensible scientifi knowledge with them. It is not so important that we share cutting-edge knowledge, but rather that what we share is understandable.

On the other hand, Couso talked about the importance of making different professional careers within the scientific path visible, such as scientific journalism. However, she highlighted the need of not becoming obsessed with the idea of the whole world working in science-related careers, but rather with anyone being able to enjoy a scientific documentary, show critical thinking and the ability to pick out real news from fake ones thanks to their knowledge in science.

“The goal should be that anyone could enjoy a scientific documentary, have critical thinking and pick out real news from fake ones thanks to their knowledge in science”

“The students are a critical and demanding audience that does not always get the image we try to transmit”, Couso said. In fact, when we want to transmit this image, there are two very dangerous ideas we need to avoid:

- The culture of excellence: no student between 10 and 14 years old consider themselves excellent in any subject.

- The culture of sacrifice and effort: it must be replaced by the culture of professionalism.

“Students tend to have a more solid position towards the scientific-technological path once they get older than 10-14 years old”

The positioning towards the scientific-technological field, that is, the way in which a person thinks, feels, speaks and acts in relation to this area, is made up of different variables:

- Interests

- Identity

- Capacity

- Aspirations

- Capacity perception

What does research tell us about the variables that affect positioning in the scientific-technological field?

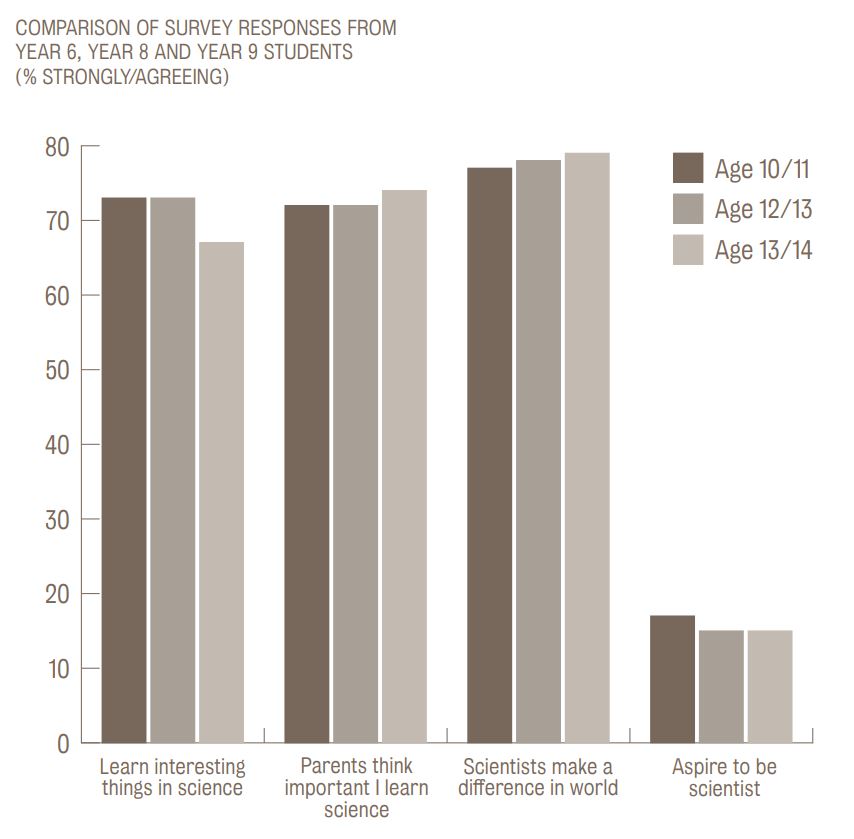

According to the ASPIRES project, aspiration has more influence than interest and is created before the age of 10, being very stable in 10-14 year-olds. In addition, people who aspire to become a scientist have a very specific profile: male student, high socio-cultural level, good grades in science and a family member connected to the scientific-technological field.

On the other hand, and closely related to aspirations, the results of the 2015 PISA study tell us that girls and boys at a social disadvantage have a much lower perception of their own efficacy (self-efficacy). That is, they believe less in their own abilities to execute the necessary actions in a given situation.

“Self-efficacy is very much related to effectiveness: if you don’t think you are capable of doing something, you will probably not do it”

Students want to know what motivated the researcher to become a scientist

Couso finished her presentation showing the aspects for which students show more interest when a scientist goes to their school to give a talk.

After asking 84 students, it was concluded that the youth want to know what motivated the researcher to become a scientist; they are not so interested in the scientific content. This interest is closely related to the identity variable since, as we have already mentioned above: we will never want to be like those by whom we do not feel represented.