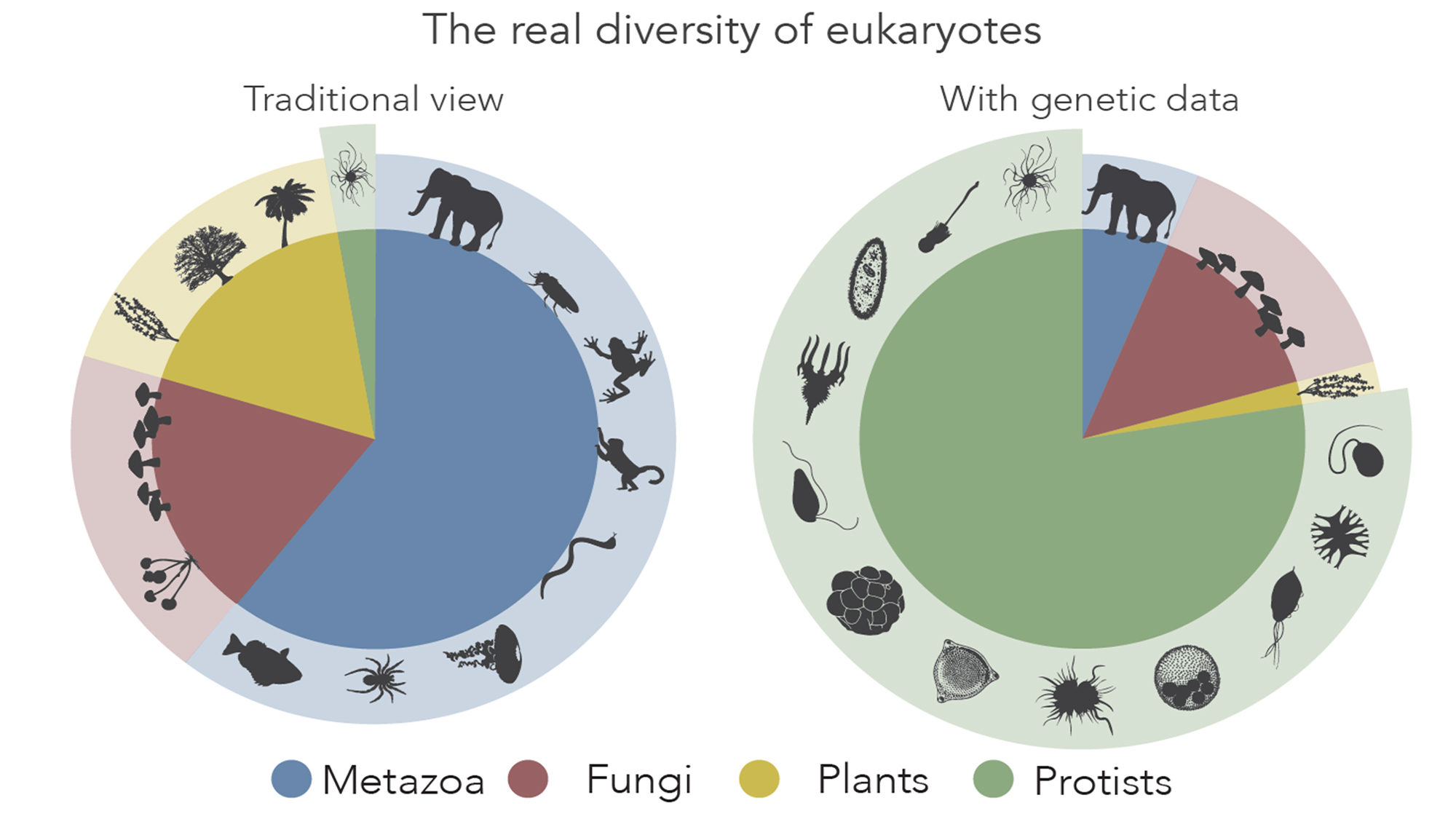

According to the traditional catalogue of species, 97% of eukaryotes, in other words, organisms with nucleated cells, are multicellular, mainly animals, plants and fungi. The remaining 3% are unicellular eukaryotes, called protists.

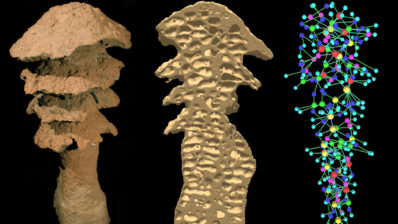

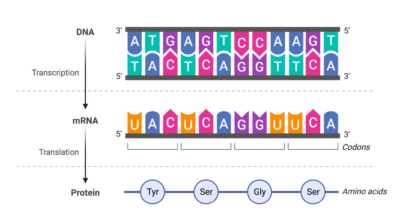

However, if we extracted DNA from a sea water sample and sequenced the 18S ribosomal gene, found in all eukaryotic cells and used to identify them, our findings would reveal a completely different panorama: three quarters of the genetic material would belong to protists, not multicellular organisms. Genomics has, therefore, switched our traditional view of eukaryotic organisms and highlighted the fact that our view of eukaryotes is partial and biased.

The reason is simple. Research has typically focused on humans and on what affects them, such as plants and fungi, because we eat them or they harm us, and certain animals like cats, dogs, and apes, because we like them. As for unicellular organisms, the most well-studied are human parasites. However, the unknown biodiversity of protists may be hiding potential discoveries and applications that could radically change our society.

Genome sequencing is a powerful tool that helps us understand the complexity of eukaryotes and their evolutionary history. This is relevant to basic research, as it can enable us to understand who we share this planet with, and to applied research, as it can potentially lead to disease treatments. Filling out the eukaryotic tree at the genomic level, based on phylogenetic diversity, should therefore be a priority for the scientific community. Because, in the end, how can we say we know what a eukaryote is, when the majority of species are still undescribed?

This text was written by Àngels Codina-Relat and Maria Ferrer Bonet.