In Catalonia, 614 people committed suicide in 2022, 38 more than the previous year, according to the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE). This cause of death is affecting more and more people, both those who take their own lives and those who survive suicide, as well as the people around them. The health system and various associations are working to combat the stigma attached to this act, to improve prevention systems and to provide better care and follow-up for those at risk.

In this direction, the European consortium PERMANENS is developing software based on artificial intelligence (AI) that can improve the care of people at risk of suicide or self-harm when they visit the hospital emergency department. Its design involves experts in clinical research, medicine, biostatistics and bioinformatics, as well as patients and people around them. The associations ‘Després del suïcidi’ and the Catalan Association for the Prevention of Suicide are also collaborating. The two women who chair them, Cecília Borràs and Clara Rubio, also participate as individuals.

“With today’s artificial intelligence techniques, we can tailor treatment to each patient’s risk profile. The idea is that we can help find the most appropriate intervention for each person”

Philippe Mortier, Hospital del Mar Research Institute

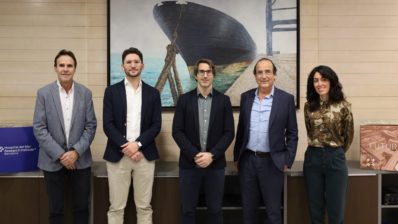

It is a project carried out by five research groups from four European countries. Working in Catalonia are Philippe Mortier, from the Hospital del Mar Research Institute and coordinator of the project, and Manuel Pastor, from the Biomedical Informatics Research Unit (GRIB), in the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences (MELIS-UPF). Other partners include the University of Oslo (Norway), the Karolinska Institute (Sweden) and the University College Cork-National Suicide Research Foundation (Ireland).

The PERMANENS project is in its first year of development and is funded by the ‘Instituto de Salud Carlos III’ and the European Union. Mortier also leads the CARES project, funded by the Fundació la Marató de TV3, which aims to improve the detection of suicide risk among patients seeking help in the emergency department for non-psychiatric reasons.

Challenges in suicide prevention

There are several factors that make suicide prevention difficult. The stigma associated with suicide may mean that people at risk do not receive adequate care from the social or medical environment. In the healthcare setting, emergency clinicians have many factors to consider when caring for someone in crisis.

It is not easy to assess the risk of suicide or self-harm, which depends on the characteristics of the individual patient. Doctors, even specially trained psychiatrists, can be overwhelmed and find it difficult to provide personalised care to such patients. “With today’s artificial intelligence techniques, we can tailor treatment to each patient’s risk profile. The idea is that we can help find the most appropriate intervention for each person”, explains Mortier.

The experience of people going to hospital emergencies in crisis can be very different. In some cases, after attending and resolving the crisis, patients do not attend follow-up appointments, which often are some time later due to waiting lists. This can lead to further crises in the future and a subsequent return to the emergency department.

To address this problem, in 2014 the Catalan government’s Department of Health launched the Codi Risc Suicidi (CRS) programme, a protocol for the care and prevention of suicidal behaviour. Since 2016, the CRS has covered the whole of Catalonia. It improves the follow-up of patients by referring them to the Adult Mental Health Centre (CSMA) and following up by telephone.

How AI can help improve the care of at-risk patients

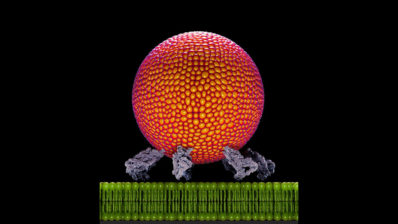

The new PERMANENS consortium project takes this a step further by developing an AI tool that can improve the care of people who go to emergency departments at risk of suicide. The AI will help doctors provide personalised care, taking into account each patient’s risk profile. It will access patient records and calculate risk scores for suicide, self-harm or disengagement from the healthcare system. It will also suggest questions to the clinician to assess the patient and the most appropriate intervention. It is expected to provide confidence to healthcare staff and help standardise responses. It can also be used as a training tool.

The data that feed this learning model come from clinical registries in each country. In the case of Catalonia, they come from the PADRIS data analysis programme for health research and innovation and from the CRS programme. “Innovative suicide prevention programmes have been implemented in Catalonia, and the data from the PADRIS and Codi Risc programmes allow us to participate in this project,” says Mortier. One of the major challenges of the project is to standardise all these data, which also come from Norway, Sweden and Ireland, as well as to guarantee their privacy.