Oocytes are the longest surviving cells in the human body. They are the precursors of all the eggs a woman will produce in her lifetime and they develop before birth. They can remain healthy for almost 50 years, which is the average time between birth and menopause in women. A team at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) has discovered a new cell structure that spares oocytes from the cellular degradation characteristic of long-lived cells.

The study was carried out on mouse oocytes, eggs and embryos. The oocytes of these rodents can remain healthy for up to 18 months, which is the fertile period for this species. As the oocytes form the egg, which becomes the first cell of the embryo after fertilisation, it is important that they do not accumulate toxins. Therefore, the research focused on the aggregates of misfolded or damaged proteins, which accumulate in the long-lived cells and degrade them. These aggregates are known to be toxic when they accumulate in neurons and lead to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease.

The rest of the body’s cells eliminate these protein aggregates by two systems: cell division, which allows the toxic substances to accumulate in a single cell and keep the other cell healthy; and their breakdown by specialised enzymes. But oocytes do not divide, nor can they constantly break down the aggregates, because this would require a great deal of energy. Moreover, since their cytoplasm will be the cytoplasm of the embryo, they have a reduced metabolic activity to avoid the generation of by-products that could harm the embryo.

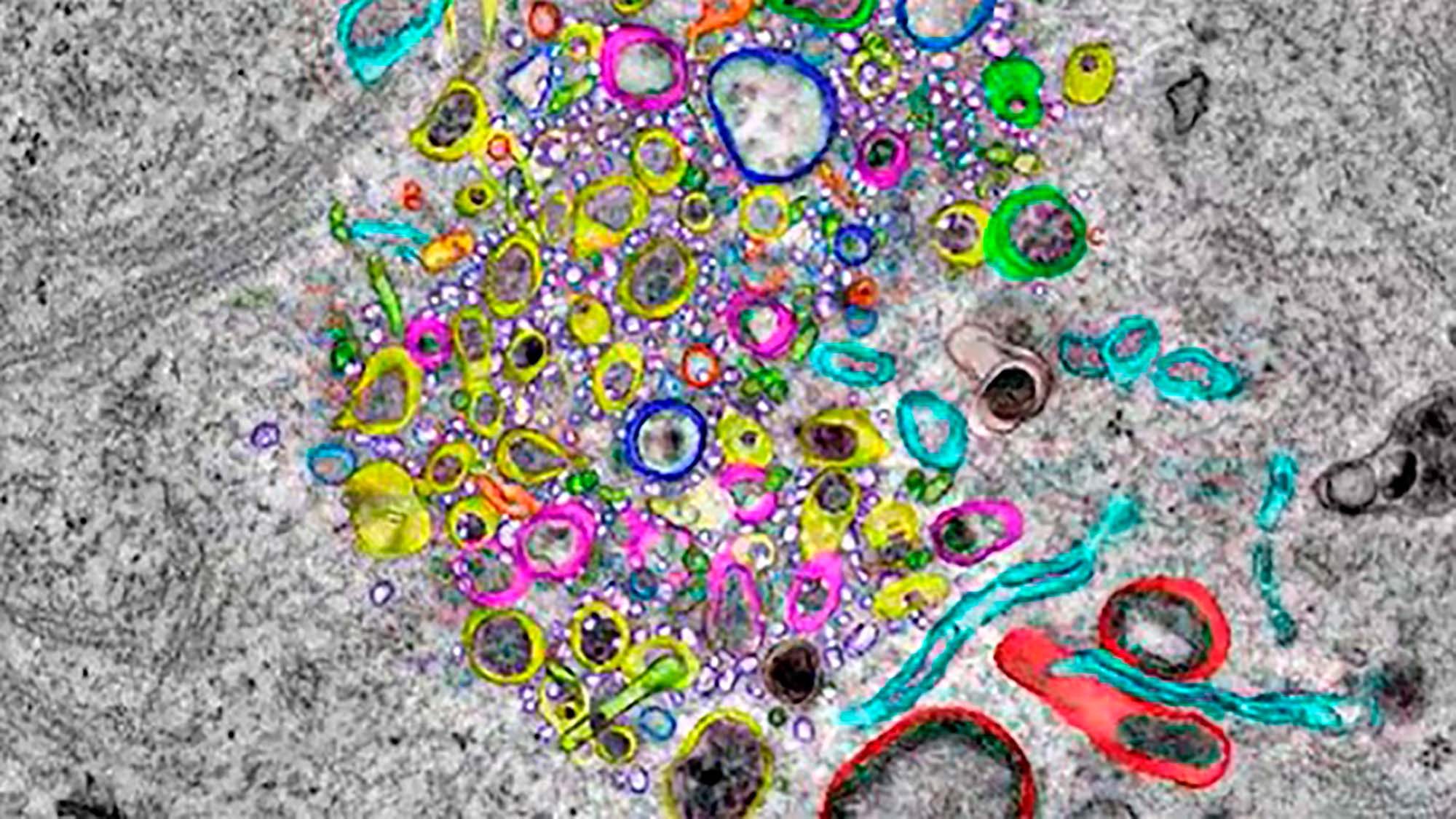

By looking at protein aggregates, the Böke lab identified structures they have named EndoLysosomal Vesicular Assemblies, or ‘ELVAs’ for short. “ELVAs are like a sophisticated waste disposal network or clean-up crew, patrolling the cytoplasm to ensure no aggregates are free-floating. They keep these aggregates in a confined environment until the oocyte is ready to dispose of them all at once. It’s an effective and energy-efficient strategy,” says Gabriele Zaffagnini, co-author of the study and leader of the research team for this project.

Each oocyte has about 50 ELVAs. They are a ‘superorganelle’ made up of many types of cellular components that work together. They hold and accumulate the cell aggregates until the egg matures. Before the egg is released, ELVAs move to the cell surface and degrade the aggregates. In this way, the egg has a debris-free cytoplasm and can give rise to a healthy embryo.

The study took five and a half years to complete. The discovery will advance our understanding of the causes of infertility, an increasingly common condition due to delayed childbearing. It may also open up new avenues of research into the existence of ELVAs in other types of long-lived cells, such as neurons, to better understand neurodegenerative diseases.

Zaffagnini, G.; Cheng, S.; Salzer, M. C.; Pernaute, B.; Duran, J. M.; Irimia, M.; Schuh, M.; Böke, E. Mouse oocytes sequester aggregated proteins in degradative super-organelles. Cell 2024; 187(5); 1109: e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.01.031