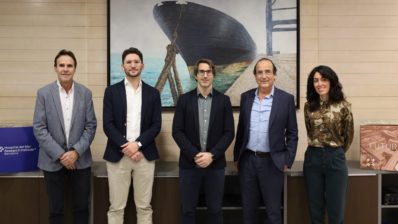

A new study by Arnau Busquets‘ group (Hospital del Mar Research Institute) and conducted mainly by PhD student José Antonio González Parra gives new clues about how the brain makes decisions based on indirect associations between different stimuli.

Indirect incidental association occurs a response is triggered by a link between two or more stimuli, as opposed to direct association, in which a single stimulus triggers a response. While the latter is widely studied, with Pavlov’s experiment being the best-known case, the former is widely accepted but has been little analysed experimentally.

In this study, carried out on mice, the animals were made to associate olfactory and gustatory stimuli. The smell of banana was associated with a sweet taste, while the smell of almond was associated with a salty taste. Then, they were subjected to a negative stimulus that was also associated with banana. From then on, they rejected the sweet taste because they associated it with the negative stimulus.

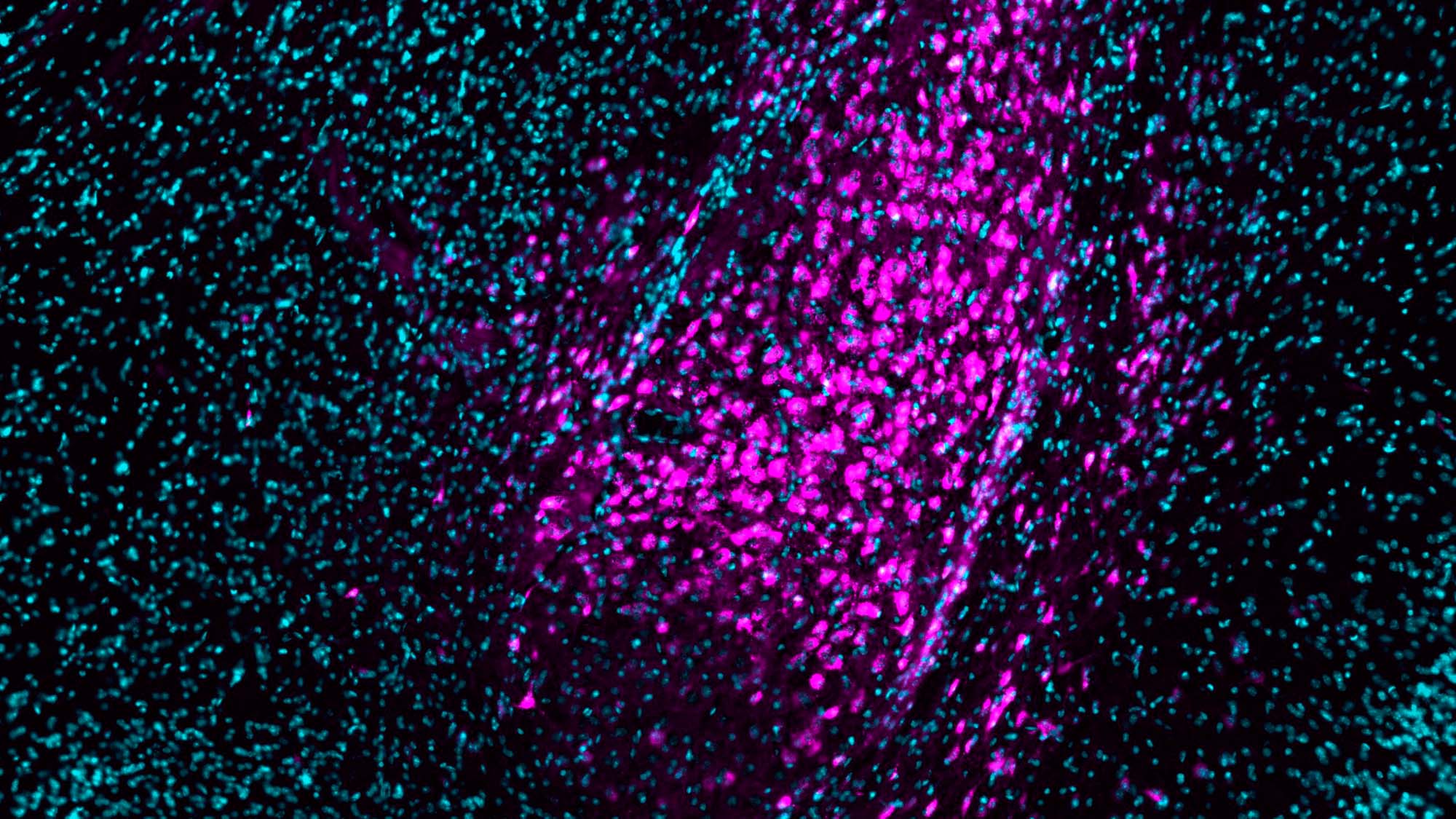

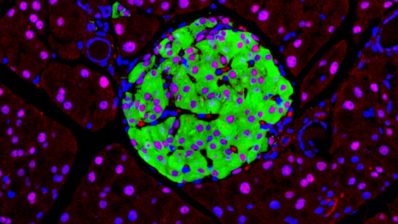

Using imaging techniques, the team identified the amygdala as the main region that is activated when olfactory and taste stimuli are associated, as well as other areas of the cerebral cortex that interact at other stages of the process. In addition, to test the role of the amygdala, its activity was inhibited with viral vectors and it was found that the mice did not create the association between smell and taste.

The amygdala is a brain area involved in the development of some mental disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder and is associated with fear and anxiety, among other things.

“Alterations in these indirect associations are the basis of different mental pathologies,” says Busquets. “Although the study is in mice, understanding the brain circuits of these complex cognitive processes can help us to try to design therapeutic approaches in humans”.

J.A. González-Parra, V. Acciai, L. Vidal-Palencia, M. Canela-Grimau, & A. Busquets-Garcia, Projecting neurons from the lateral entorhinal cortex to the basolateral amygdala mediate the encoding of incidental odor–taste associations, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2025), 122 (23) e2502127122, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2502127122