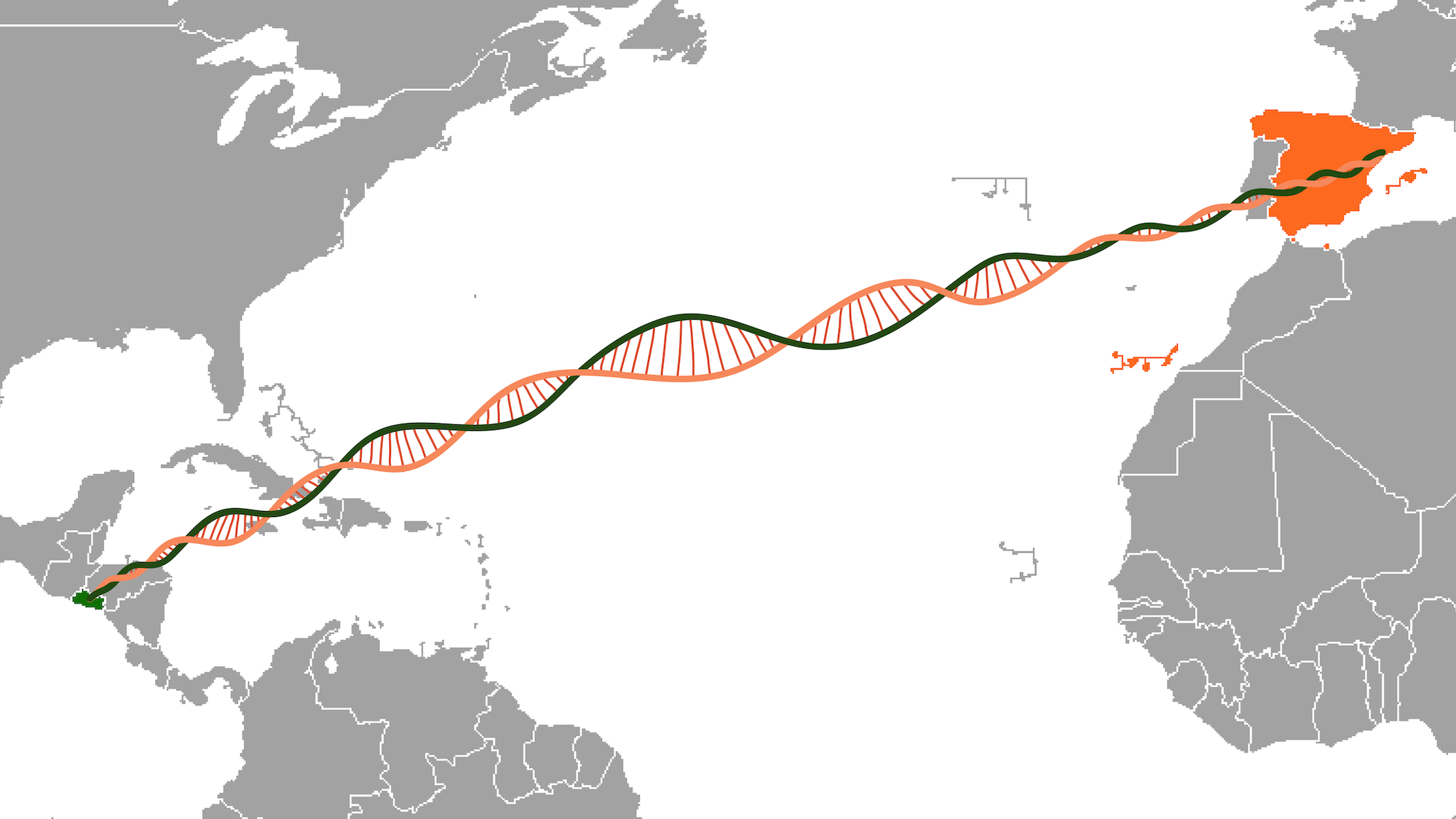

During the civil war in El Salvador from 1980 to 1992, hundreds of children disappeared, many of them presumably stolen and given up for ‘adoption’. Thanks to UPF and IBE researchers, the families of these children will now find it a little easier to identify their lost relatives.

Following a study carried out by the UPF genomics service a few years ago, where they had identified the remains of mass graves from the Spanish Civil War, the Pro-Búsqueda Association contacted them from the other side of the Atlantic with a proposal: to help them create a genetic database of the population of El Salvador using the latest technologies.

Little money can go a long way

The project, one of the first where mass sequencing is applied to forensic genetics, has been carried out thanks to 50,000 euros donated by the Catalan Agency for Development Cooperation (ACCD), plus 3,000 euros from UPFSolidària.

It consisted of two distinct parts:

- Training: El Salvador researchers have spent three stays of 2-3 weeks learning new forensic technologies. In addition, the genomics unit has developed a free, open-access online forensic genetics course so that research staff from other countries can also learn these innovative techniques.

- Sequencing and analysis of more than 100 regions of the genome of 400 volunteers from three areas of El Salvador.

Saliva samples arrived from the Latin American country to Barcelona. On the 7th floor of the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB), in the Genomics unit of the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences, Pompeu Fabra University (MELIS-UPF), DNA was isolated and some 150 markers (different points in the genome) were sequenced in each sample. Later, in the laboratories of the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF), in the same building, they analyzed the frequencies of each variant. “Each of these markers can have between 2 and 30, or sometimes more, different variants in the population,” explains Francesc Calafell, an IBE researcher. “What we are interested in knowing, and until now it was not known, is the frequency of each of these variants in the Salvadoran population. Thus, by comparing two samples we could know whether the probability that they have the same variants of a marker by chance, without sharing any blood relationship, is high or low. By doing this for the 150 markers, it gives us a very precise indication of the probabilities of kinship”.

“We have shown that with a moderate investment you can make very valid research projects, with training and added value”

Ferran Casals, former head of the genomics unit at UPF

Genetic databases

When it comes to forensic genetics studies, there are two main types of databases.

- Those with genetic profiles of specific people, used directly to solve cases. For example, in the UK, everyone who has been in contact with the justice system has a genetic profile, with the minimum points needed to identify the person but not enough to obtain information beyond identification. When there is a criminal case where there is a biological sample, it is confronted against this database to try to identify the person to whom the sample belongs.

- Those with anonymous genetic profiles, which give an idea of genomic variation at the population level. Apart from many other uses in forensic genetics, they are used in cases of historical memory, to understand the probability of a genetic relationship between a current sample and an unknown sample (mass graves, etc.).

The El Salvador database belongs to this second type. However, thanks to the work of the UPF / IBE research team, it has characteristics that allow it to go much further in its investigation of the past than these databases usually do.

More markers and new technologies

In forensic genetics, Calafell explains, there is an established and standard set of markers that are commonly used. But in this study, they used more markers than the standards. This, in addition to using new sequencing technologies, allowed them to go beyond parent-child relationships.

“In most cases of routine forensic genetics, there’s no need for so much precision. But in cases such as wars or disappearances, where the person may be looking not for their parents but perhaps for their uncle-grandfather, etc. more markers are needed, because the more distant the relationship, the more similarity we lose at the genetic level“, says the expert in population genetics. “In addition, over time, DNA is damaged and some markers may no longer work. Having redundancy allows you to keep the information”, he said. To make an analogy, with all these markers and the level of detail with which they can analyze them, it is as if instead of seeing if a person is A+ blood group, they could distinguish between several subgroups of A+ (A+1, A+2, etc.), and thus be more precise.

“In this database that we have created of the population of El Salvador, there are more markers than usual, and from each one we can extract more information”

Francesc Calafell, group leader at the IBE

Research and cooperation

Genomic data has been obtained anonymously from the general population, and the frequencies of the different variants have been made public for use by those who need it.

This new project and the resulting database will help the Pro-Búsqueda Association do its job better. The association, which has already resolved more than 400 cases of children given up for adoption in a context of violence, manages a database of genetic profiles of relatives who continue to search for their missing children. Knowing the genetic frequencies of the Salvadoran population will make the comparison much more informative.

“It will also be useful for the search for other missing Salvadorans, both due to the current violence in the country and for those who disappear on the migratory route to the United States. For these, a forensic work for their identification has already started”, explains Patricia del Carmen Vásquez Marías, from the genetics research unit of Pro-Búsqueda.

“This contribution to our country, through the population genetic study for forensic purposes, demonstrates the importance of the application of science to human rights violations”

Patricia Vásquez Marías (Pro-Búsqueda)

“We want to encourage the study of genetics in our country in order to identify those missing, and thanks to projects like this we are achieving this aim”, adds Eduardo Garcia, Executive Director of the association.

This is not the first time that the scientific team of the UPF genomics unit has taken part in a study with this more social aspect. They had done the same thing before – creating specific databases to find out the variation within each population – with Catalans and gypsies.

“In our environment, where we work mostly with basic research, projects like this where research is a form of cooperation are very rewarding and bring us closer to the people.”

Núria Bonet, current head of the genomics unit at UPF

In short, it has been an innovative project, where the most advanced DNA sequencing technologies have been applied to forensic genetics and where, in addition, “the exchange and collaboration with researchers from El Salvador have been extremely stimulating. and enriching for all”, concludes Casals.

Casals et al. A forensic population database in El Salvador: 58 STRs and 94 SNPs. Forensic Science International: Genetics, December 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2021.102646.