A group of researchers from the Institute for Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF), a mixed center of the CSIC and Pompeu Fabra University, in collaboration with Harvard University, has developed a genetic map of the last 8,000 years of the Iberian Peninsula.

The study, published in Science, has analyzed the genomes of 271 inhabitants of the peninsula from different historical periods and has contrasted them with the data collected in previous studies of 1,107 ancient individuals and 2,862 modern ones.

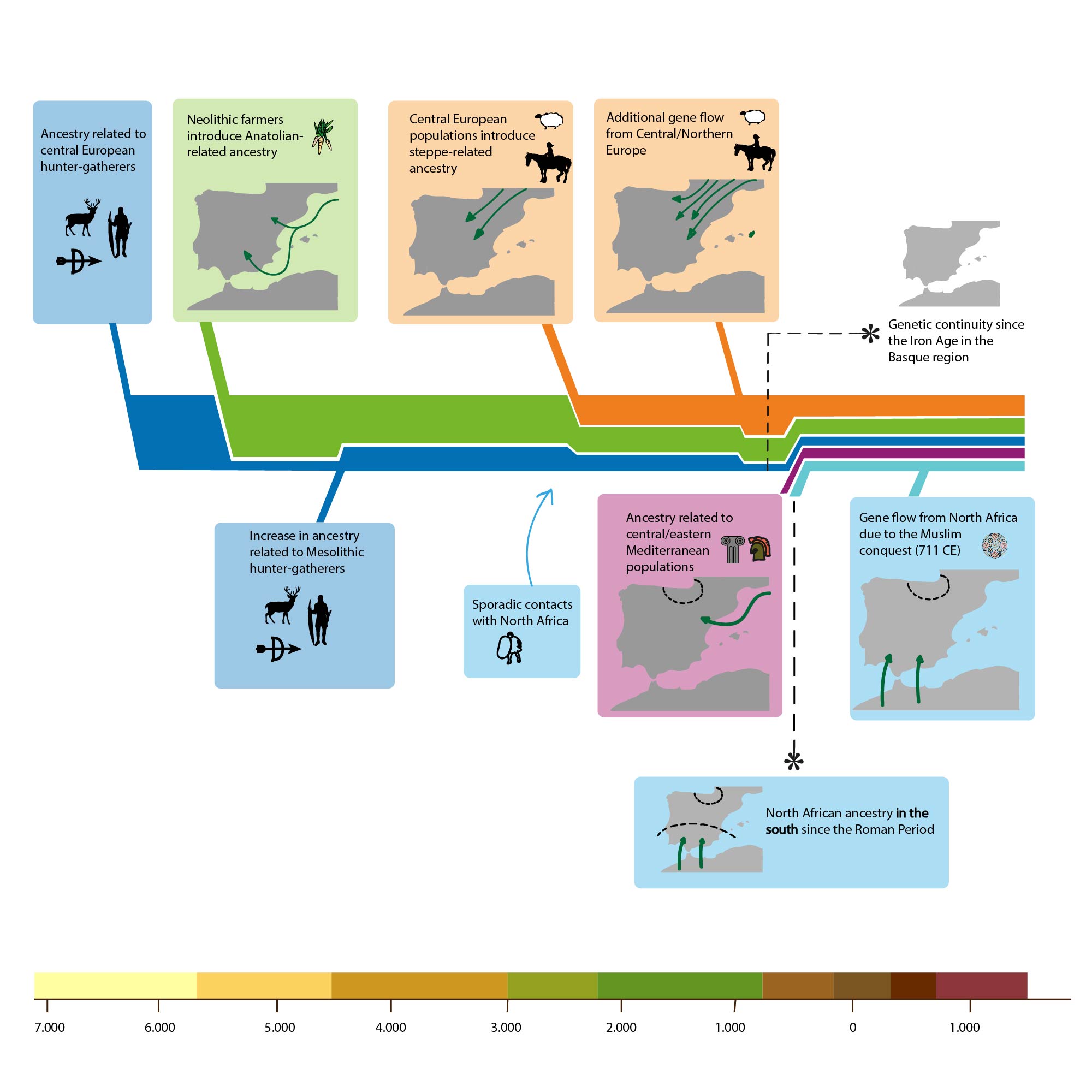

The results show an unprecedented image of the transformation of the Iberian population throughout the different historical and prehistoric stages.

- A total replacement of the male population in the Bronze Age: At about 4,500 BC the descendants of shepherds from the steppes of Eastern Europe arrived on the peninsula. During the next 400 years, the lineages of local Y chromosomes were gradually replaced by a lineage of steppe ancestry. This means that almost 100% of men (as well as 40% of the general population) were replaced by the newcomers, although the causes are unknown. According to the authors, there is no evidence of widespread violence in this period.

- Basque genetics has hardly changed since the Iron Age (about 3,000 years ago). Until now it was believed that the Basques were direct descendants of the first farmers (4500 BC) or even the Mesolithic hunters (6000 BC). This study, however, shows that, like the rest of the Peninsula, the area of the Basque Country also received genetic influence from the steppes until the Iron Age, around 1000 BC. From then on, they were isolated, not being affected by the migrations of the Romans, Greeks or Muslims.

- African contacts are older than previously thought: The study found, at sites in Madrid and Cádiz, a couple of individuals with African descent who lived in the Peninsula about 4,000 years ago. These are sporadic contacts, but show that there was an African presence long before the arrival of Muslims on the Peninsula in the 8th century. The scientists also detected a gene flow from North Africa to the Southeast of the Peninsula in Punic and Roman times.

- Romans, Greeks, Phoenicians, Visigoths and Muslims: Based on the analysis of 24 individuals from the Greek colony of Empúries, founded between the 600s and the late-Roman period in present-day Catalonia, scientists have concluded that at the beginning of The Middle Age of at least a quarter of Iberian ancestry had been replaced by new flows of population from the Eastern Mediterranean (Romans, Greeks and Phoenicians). The researchers also analyzed two individuals of Visigothic origin at a site in Girona and several of Muslim origin in Granada, Valencia, Castellón and Vinaròs. These ‘ancient Iberians’ showed a North African genetic component of almost 50%, while in the current population it is 5%. “This North African ancestry was almost completely eliminated during the Reconquista and the subsequent expulsion of the Moors”, says Carles Lalueza-Fox, one of the directors of the study at the IBE.

An important novelty of the article is that it has analyzed for the first time samples from the last 3,000 years, a period for which no samples were analyzed in the Iberian Peninsula.

Biology and genetics, hand in hand with archeology and anthropology

The authors of the study emphasize that genetic data alone is not enough to understand the whole story. “We need to take into account the evidence from fields such as archeology and anthropology to better understand what led to these genetic patterns,” says David Reich, co-leader of the study at Harvard Medical School.

Indeed, the article has 111 authors, 87 of whom are archaeologists. “In the last 4 years I have been collaborating with archaeologists from all over Spain to get access to the samples they found. Their contribution has been essential for the development of the study”, explains Lalueza-Fox.

You can read more about the study on the IBE website and see a graphical representation of the results in the following video:

Iñigo Olalde et al. The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years. Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.aav1444