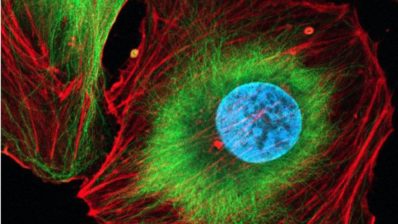

Genigma is a citizen science experiment to explore the human genome in a collaborative way. To involve citizens in the research, an app has been created for mobile devices to analyse the genome data of cancer cells to find the order of sequences and any anomalies.

Elisabetta Broglio, facilitator of citizen science projects at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) and project manager of Genigma, tells us more.

How did the idea of creating this project come about?

The original idea came from two postdocs, Marco di Stefano and Juan Rodríguez, from the CNAG-CRG, who in 2019 were working in the Structural Genomics Group led by Marc Martí-Renom. In their daily work of 3D genome analysis, they always resorted to manual adjustments to fine-tune some parameters that the algorithms were not able to define well.

These arrangements of the computer results turned out to be an essentially visual and logical task, so they came up with the idea of turning it into a game to involve people and speed up the research. They then applied to an open call from the ORION Open Sience project and contacted me for advice on essential aspects of citizen science, a methodology they were completely unfamiliar with.

As soon as the funding was obtained, we started working together on the project. I proposed, among other things, to start by opening the idea up to citizens with 3 co-creation sessions and we involved 120 people with very diverse profiles. That was in 2019!

What do the players bring to the table that the algorithms lack?

Algorithms, when faced with the same problem always give you the same result; so to speak, algorithms all play the same. People, on the other hand, play differently and can come up with more creative answers. It is precisely this human creativity and social intelligence that we seek to exploit with Genigma.

Tell us a bit more about the game; how does one play?

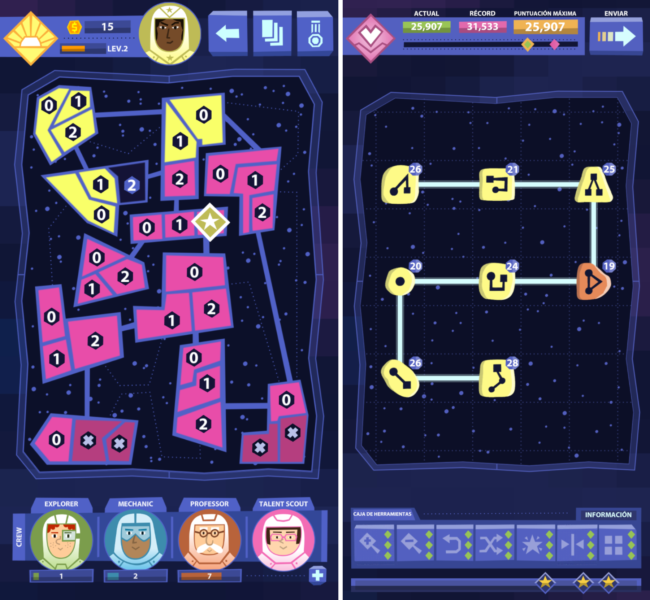

In Genigma there are 4 clans that compete weekly to contribute the most data to science. The objective is to solve different puzzles by arranging the pieces (which are fragments of DNA) to get the highest score and send this data to the scientific team.

In addition, there are a number of virtual tools in the game that can help to achieve this high score and, as a reward, science stickers can be collected.

The aim of the game is to solve different puzzles by arranging the pieces, which are fragments of DNA.

What is the #GenigmaChallenge?

Genigma was launched on 27 January as an experiment. We then set a collective challenge, the #GenigmaChallenge: to obtain in 90 days the necessary data to decipher the reference genomic map of the T47D breast cancer cell line. To do this, 30,000 players are needed to play a minimum of 50 games each.

Each week, the scientific team introduces new puzzles for the players to solve. If we manage to solve the genomic map of this cancer, we could consider including other cell lines from other types of cancer. In other words, if the experiment works, it could be exportable to other types of data.

How present is science in Genigma?

Here we had a big dilemma and there was a lot of discussion about what to do. But in the end we decided to create a game that could reach any kind of audience, whether they were interested in science or not.

For this reason, and as suggested by several people who participated in the co-creations at the beginning, the science part has been introduced in the form of cumulative cards (there are more than 200) that explain some concepts related to the genome, cancer and open science and also provide curious facts. We also provide weekly information on the partial results obtained from the chromosomes being analysed, with a pop-up and a link to a web page.

This week we have also launched a teaching guide with exclusive science material, created to engage high school teachers and students in the #GenigmaChallenge.

What did you expect to achieve with the project?

Beyond obtaining the data that will help us create the breast cancer genome map, another of the objectives was to raise awareness of citizen science as a methodology, also among other scientific teams. To let people know that there are ways to participate in research by dedicating part of their time and knowledge to real projects. And to show scientific teams that it is possible to create collaborative projects, also in disciplines such as basic science.

And you succeeded!

Obviously we had hoped that people would like the game, but we didn’t foresee this response. It’s been incredibly well received. One month after the launch, more than 30,000 people have downloaded the app and are playing in more than 130 countries around the world. In the first few weeks we have already solved 100% of 2 chromosomes and we continue to advance day by day to meet the challenge.

It is very nice to see how the game has managed to attract the attention of so many people and to see that there is a desire to be part of a community that collaborates for the same cause.

Do you think more citizen science projects are needed?

Of course they are! This type of project adds great value to the relationship between science and citizens. Science can work in a more horizontal way, listening to the needs of society and making citizens part of the project. If this relationship is honest, it manages to create this connection with real and current science and expand it.

“Citizen science breaks all the moulds: it allows you to go further, not only at the level of big data, but also mentally. It implies a different way of working, realising the time and value that people contribute is something that cannot be achieved locked up in a laboratory”

Elisabetta Broglio

What advice would you give to someone who wants to start a citizen science project?

To look for a good multidisciplinary team with people who have complementary skills and different visions – and to be very patient because it is a long process! And this is a critical point. You have to get parallel funding to help sustain the project over time.

Projects have a long gestation period and the first funding always runs out at some point. The natural rotation of science also means that postdocs move on: in fact, Marco and Juan are no longer at CNAG and, although they are still very active in the Genigma scientific team, new people have joined and new formulas are needed for the sustainability of the project. It has taken more than 2 years to create the Genigma game, and now that it is out there, it needs to be maintained!

What surprised you the most about Genigma?

I have been very positively surprised by the change that the scientific team has undergone during the whole creative process. It was their first citizen science project and together we have learned a lot and we are collaborating in a transversal way, dissipating the barriers between disciplines. There has also been a very special involvement of the teams of contracted professionals, which has gone far beyond what was stipulated for a project of this style.

I have also been surprised to see how we have overcome geographical borders thanks to the important effort we are making in communicating the project and the preliminary results. And, of course, I am overwhelmed by the response, the complicity and the effort of all the participants in the first phases and those who have now signed up to play. Hopefully by the end of April, we will be able to announce that we have all the data needed to build the genomic reference map of breast cancer and that we have obtained it collectively with people from all over the world!

“Having the breast cancer reference map would give us more information to identify new targets and therapies to help patients in the future”

Roni Wright, breast cancer researcher using the T47D cell line

Thank you very much Elisabetta and congratulations on this collective project!