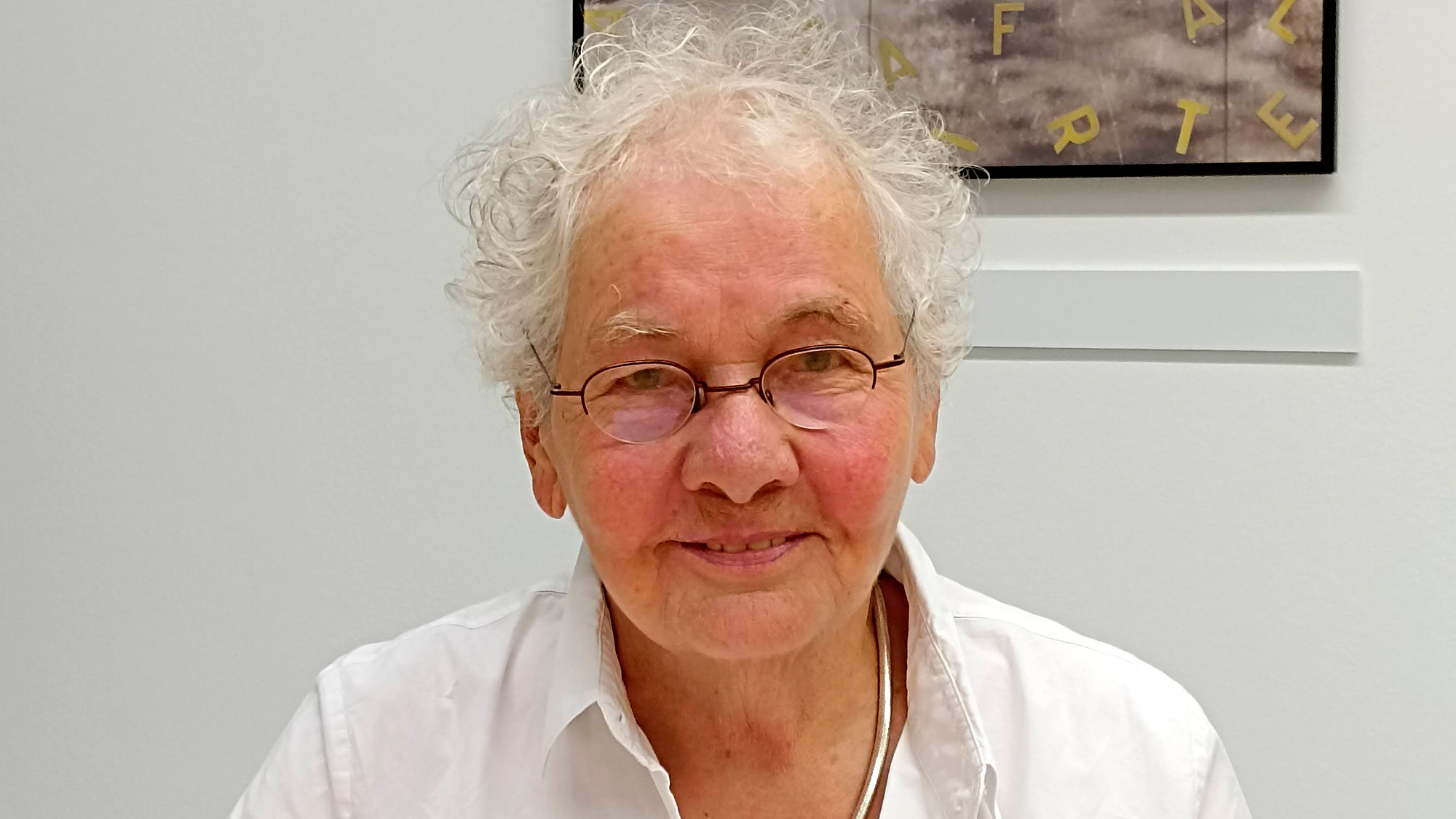

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard is a developmental biologist with a really long record of awards – including, of course, the Nobel Prize. She received this award in 1995, together with her colleagues Eric Wieschaus and Edward B. Lewis, in recognition of their research on the control of embryonic development, which they showed was due to the sequential action of several genes.

This July 12th, 2022, a new recognition was added to her list – her nomination as Doctor Honoris Causa by the “young, modern and internationaly University Pompeu Fabra”, in her own words. She received this honour at the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB) auditorium. Cristina Pujades, a researcher at the UPF, read her laudatio to the German scientists in a ceremony accompanied by piano, flute and song.

We took the chance to interview Nüsslein-Volhard about her career.

With such an extensive list of recognitions – even an asteroid with your name! – what is the thing that you are most proud of from your career?

I think what I’m most proud of is to have had the courage to choose Drosophila as an experimental system, because that meant having to develop a whole new field. And now, in part thanks to my early work, the fruit fly is one of the most used models in developmental biology!

And what prompted you to study Drosophila?

When I studied biology, molecular biology was a prominent part – but only with bacteria. At the end of my thesis, I was encouraged to look for higher organisms. So I looked around for an organism where I could combine developmental biology and genetics, to unravel the logic and the mechanisms of constructing an embryo. Understanding development is very hard, so I thought going for the genes could help dissect complex pathways.

There had been studies with flies, but mostly with the adult– people thought the embryo was too complicated. That was probably a big breakthrough; looking at the embryo and the effects of mutations in the larvae, which have a rich enough pattern to allow us to screen for mutations. We found 130 genes whose mutation affected this pattern, and these genes provided the bases for the work of the Drosophila community afterwards.

You not only established Drosophila as a model for development but also zebrafish.

At the time of this screen it was not so clear how much of the fly work would apply to vertebrates. Their mode of development is so different that many people thought they could not have common processes; that we could not learn from flies. This was, again, a challenge. There were groups working with mutant fish but they could not grow them efficiently. So, we worked for 3 or 4 years to develop methods to grow zebrafish in large scale.

Looking back, can you speak of any challenges you have overcome?

I guess it was not easy to find jobs at the time… I was lucky to get a position at the EMBL, although in a way it was an act of discrimination, because they only offered me the job when they found Eric Wieschaus to join me; they didn’t trust a woman to run a lab alone! But again, it was lucky, because Eric and I worked very well as a team.

How about any regrets?

I think after the Nobel Prize I made the error of becoming too involved in other activities. One big mistake, for example, was to become co-founder of a company on zebrafish. I really have no sense for these things, and either way it was not successful.

But just in general, I was part of many committees, had to give many talks… Although this was challenging and exciting (I was, for example, part of the National Ethics Council of Germany), they distracted from the lab work. My lab was not at the same standard as it used to be – which happens to many people when they get too busy! Also, when you are too much in the public doing this kind of things, you have no time to get new ideas, because you are just repeating the old ones over and over. So I stopped giving talks; which meant I got a bad reputation! And when I got close to retirement I had a smaller group that I really took care of, cancelled many duties and had more time to spend on research. In the last 10 years we have been very successful with a much smaller group than before. I’m quite proud of that.

Talking about being part of many committees; this is something that tends to happen to senior female researchers…

I always warn women not to take too many of these responsibilities. If you embark in such a duty, you must make sure that it is making a difference that you are there; if you are just a number, to raise the percentage of women, then you shouldn’t do it, because it’s a waste of your time.

“Sometimes it doesn’t really help having women in committees, because they are seen as biased, and not listened to”

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard

What advice would you give to your younger self?

Definitely, after your PhD leave your supervisor, and if possible change fields to choose your own project. Many people don’t change fields because they feel they’ve already invested a lot. But when you start a PhD you often don’t really choose the topic, it’s quite random. So it’s important at some point to step back and ask yourself what it is that you really want. And the choice of topic must really fascinate you; not just something someone else told you, or that you think will lead to many publications.

“Choose your own project; step back and ask yourself what it is that you really want”

Also, don’t spend too much time complaining about discrimination; just do your job. Be careful how many professional duties you take beyond your own work. To be a scientist is a though job. There are many more people wanting to be a scientist than positions. There is so much competition, other people are so good, and you have to push really hard to be successful.

In 2004, you started the Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard to help promising female German scientists with children by paying them to get help with childcare and housework.

Yes, because every woman knows how hard it is to run a house! There is an expectation from society that women are responsible for this. And many women have this expectation themselves, and have a hard time letting others (like their husbands) help. But science is not a part-time job…

What would you have done if you had to choose a different career path?

I’d probably be a musician. I actually play the flute and I’m taking singing lessons; and I’m taking them very seriously!

You have already published several books; will the next thing be a CD?

Actually…. I already have recorded a CD! Singing Brahms. But it’s not very good.