Even though embryonic development is very similar across mammalian species – with embryos being almost undistinguishable from each other during embryogenesis– the speed at which different species develop is very varied. For example, a human embryo takes 60 days to get to the same stage as a 20 days old mouse embryo.

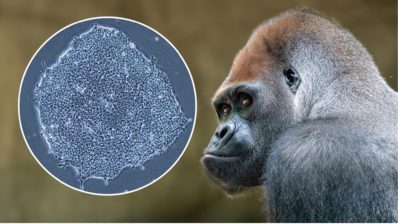

The lab lead by Miki Ebisuya at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory – Barcelona (EMBL Barcelona) has been studying this phenomenon for several years. Now, they have created a ‘stem cell zoo’ representing six different mammalian species to compare their development in the lab.

The team used in vitro models of human, mice, marmoset, rabbit, cow and rhinoceros to try and find a reason for their inter-species differences in development speed. They did that by recapitulating their segmentation clock – the oscillatory gene expression controlling the formation of the body segments that will give rise to the vertebrae that form the spine.

The stem cell zoo consists of six mammalian species, and has been used to study the segmentation clock; the oscillatory gene expression that formes the vertebrae.

“The reason to look at the segmentation clock is that the spine is formed modularly– a new vertebrae is added with every oscillation, one by one”, explains Jorge Lázaro, a PhD student at the lab and first author of the article. The frequency of these gene oscillations is different in each species, with some animals showing faster oscillations than others. Therefore, the segmentation clock serves as a nice system to compare developmental time across species.

The group’s first hypothesis – that development was slower in bigger animals – turned out not to be correct, since the rhino cells oscillated faster than the human ones, and those of the tiny marmoset were slower than humans.

However, they observed that the oscillatory period of the segmentation clock did scale with the speed of the biochemical reactions, suggesting that changes in the biochemical rates might be a general mechanism to control developmental tempo. The Ebisuya group had previously seen something similar in mice and humans, but the current work has expanded it to other species from different taxa.

“To confirm whether these findings could constitute a universal principle of mammalian development, we need to expand the zoo and include a wider range of species and phylogenies”

Miki Ebisuya, head of the group at the EMBL Barcelona

The stem cell zoo might also be useful to investigate other characteristics of animals that are hard to keep in the lab. “Many animals have particular features that make them interesting to study, for example the size of a rhino, or the long neck of giraffes, but due to practical or ethical reasons we don’t have access to them in the lab. Our stem cell zoo could help us learn from different mammalian species outside of the classic human and mouse models”, concludes Lázaro.

Ebisuya M., et al. A stem cell zoo uncovers intracellular scaling of developmental tempo across mammals Cell Stem Cell 20 June 2023. 10.1016/j.stem.2023.05.014