About 100 people joined the zoom round table on “Maternity in science” celebrated last February 15th in the context of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science.

When we think of women in science, everyone agrees there is a problem. According to the Unesco Institute for Statistics data, less than 30% of the world’s researchers are women. In some fields the trouble is already the recruitment, for example in physics or mathematics – and even more in engineering or computer sciences, with less than 20% of female students (data from UCAS; the UK university network).

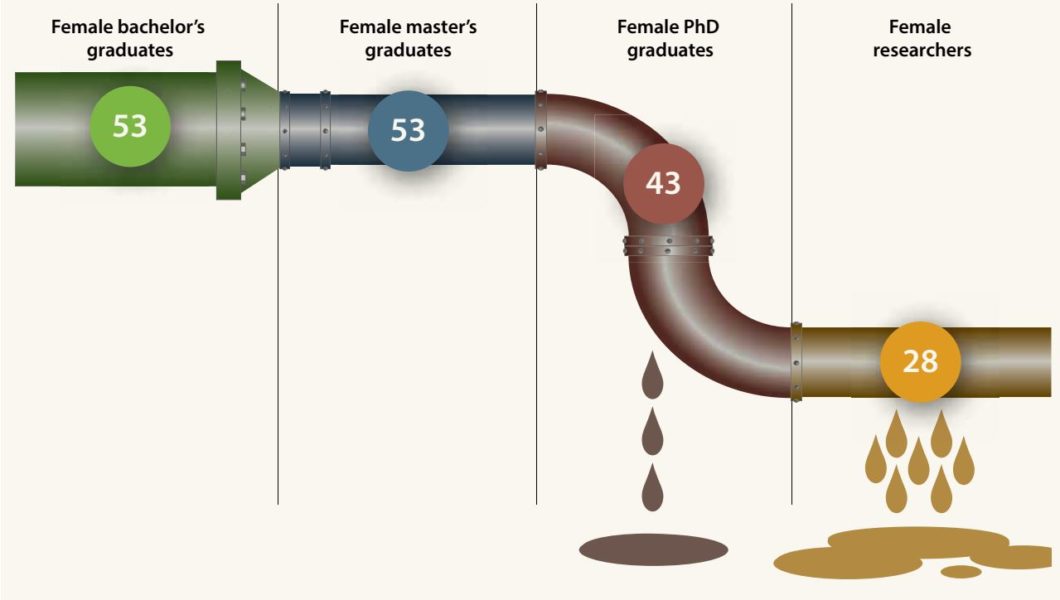

In life sciences, recruitment is not an issue, with more than 50% of women graduates (data from UNESCO). But retention and career advancement are. Hence the famous scissor graph, or the leaky pipeline, in which the number of junior female researchers is higher than men, but the trend is completely reversed as career stages advance.

The reasons for this are multiple, and complex. Women face many “invisible barriers” which partly explain this phenomenon: from gender roles since we are little kids, to gender bias and discrimination or even sexual harassment at work, to last but not least, the so-called maternal wall.

This last barrier is what “Mothers in Science” is trying to break. Isabel Torres is the co-founder and CEO of this nonprofit organisation that seeks to “advocate for mothers in STEMM and to promote equity in the workplace and the inclusion of mothers, fathers and caregivers”. She was the moderator of the round table organised by the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB) and the IDIBAPS.

Women are the majority in junior career stages in life sciences, but their percentage diminish as career stages advance. Many invisible barriers are to blame for this.

What the data show

The researcher-turned-communicator (and solo mum of 4) started the event with some data from a pre-pandemic survey conducted by Mothers in Science and partners to find out how or why parenthood had affected the career of researchers.

From the nearly 9000 respondents from 128 countries all over the globe, 34% of mothers (versus only 12% fathers) had left full-time STEMM careers upon having children, changing to part-time work, taking a more “child friendly” job, moving to another career sector, or leaving the workforce all together. The study also found a publication gap between mothers and fathers, not only in the years after the birth, but during their whole career.

34% of mothers (versus only 12% fathers) had left full-time STEMM careers upon having children, according to a survey by “Mothers in science”

“Because these barriers are mostly invisible, when a mum starts lagging behind in her career, she is blamed for not doing enough – by others and by herself. This leads to more work, self-sacrifice, etc… but it’s never enough – until you reach burn out. You reach the point where it seems you have to choose: family or career”, says Torres.

But is this a personal choice, or is it hiding structural discrimination?

Assumed personal choice hides structural and societal barriers, according to Torres, with some of the structural issues that make up this maternal wall being:

- lack of childcare (expensive, unavailable…)

- unequal parental leaves – it is normalised that mums should have longer leaves; but this creates inequalities and an unbalanced family dynamics that may perpetuate

- motherhood penalty: there is a salary gap between men and women, but this is even more so for mums, with a 5% penalty in the salary for each child, according to studies in the US

- pregnancy/maternity bias and discrimination – widespread according to their study, because mums are assumed to be unavailable, less competent, etc. Indeed, 40% of mums and 10% of dads said they had been offered fewer professional opportunities and 1 in 3 mothers (and 1 in 10 fathers) said their competence had been questioned since having children.

- inflexible work culture: with the workplace built for the ‘ideal’ worker, i.e. someone who is always available and 100% devoted to work.

- uneven division of unpaid labor – men are nowadays a lot more involved with children care, but women still spend up to 3 times more hours on house chores/childcare – and the family mental load is also more frequently for women

Personal experiences

After the introduction, the five speakers of the round table – two mums, two dads and a female researcher with no kids – shared their personal experiences.

Although they were not part of the research mums whose careers were somehow truncated by motherhood – they were all established, successful scientists – most of them agreed their careers had been indeed affected by having children.

For Gemma Moncunill, an immunologist, assistant research professor and a PI at Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) with 2 children and married to a researcher, maternity has affected her career at many levels. “It determined where I did a postdoc, to be able to raise my child together with my partner. I declined job offers to be close to my extended family. And on a daily basis it does affect my productivity, because I choose to take quality time with my children”. It has also come with good things, though – maternity has made her more efficient, she’s learned to prioritize, multitask – and has become a better mentor. Other mums – both in the panel and in the audience – agreed, and wondered whether, in that sense, motherhood should actually be a positive asset when considering who to hire, rather than negative. “The problem is structural”, Gemma said. “The system assumes that to succeed in science we need to invest a lot of extra time writing grants, disseminating our research, going to conferences, etc. We need changes in policies and conciliation – starting with simple things like not scheduling meetings after school hours”.

“Maternity determined many aspects of my career, and on a daily basis it affects my productivity. But it has also helped me be more efficient and a better mentor”

Gemma Moncunill (ISGlobal)

José Maestro, a senior researcher at the Institute for Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF), agrees. He has 3 children and is married to a teacher, and he has also declined offers in order to stay close to his family. “As parents we often choose not to use the extra time that other colleagues may be using. And this can be a disadvantage, because we are evaluated very numerically, by the number of papers we publish. Agencies or promotion processes should take into account the personal situation of mothers – and to a degree fathers, too.”

“As parents we often choose not to use the extra time that other colleagues are using. And this is a disadvantage, because we are evaluated by the number of papers”

José Maestro (IBE)

Itziar Salaverria, a junior group leader from August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), whose partner works in IT, shared her different experiences of having three children at 3 different times. “The first one was after a very productive time, so I was quite relaxed, while with the last one I was already a group leader, was preparing grants, had students to supervise… so I could not really disconnect”.

“Maternity has not changed my career; rather my career has changed my maternal experience”

Itziar Salaverria (IDIBAPS)

Giuliana Magri, a Miquel Servent independent researcher from Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (IMIM), who has no children, added: “In my case, precariousness and insecurity are related to my decision to continue delaying having children. We need to change the institutions and policies, but also our culture, this idea that we need to make a choice. That if you have a child, you are choosing family over career, and if you choose career you cannot have a family. I’ve been in New York, where there’s no parental leave at all, and in the Netherlands, where it is much more common to work part-time, there’s more conciliation… but the cultural issue remains the same, everywhere”.

“We need to change our culture, this idea that we need to make a choice between having a career and having a family”

Giuliana Magri (IMIM)

Sergi Aranda’s experience is consistent with this. The staff researcher at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) sayas: “I had two of my three children in Sweden, where we had 480 days of shared parental leave (we took 50-50 with my wife, also a researcher). Different countries have different policies, but somehow the problems remain the same; probably because they are not properly implemented. Maybe we need to find what it is that the mums that leave research find somewhere else, and bring that into academia”. Aranda also stressed the importance of choosing the right partner; someone who will share tasks as equally and fairly as possible and give you the same opportunities – an idea echoed by the rest of the panelists.

“It is crucial to choose the right partner, someone who will share tasks equally and fairly. But also in the lab, colleagues who will support you”

Sergi Aranda (CRG)

Several specific ideas to solve some of the pervasive issues around maternity in science came up during the round table:

- grants / evaluations that take into account motherhood (to a different degree than parenthood, since mums are more greatly affected)

- normalize flexible working, and denormalize working over hours

- respecting family hours – not scheduling meetings in the afternoons

- finding good partners – in your family, but also in the lab

- compulsory parental leave for both mothers and fathers

- having lactation rooms at work

- financial support to hire a technician to continue with the experiments while you are away

- having the possibility to explain your personal situation regarding your productivity; not only mothers and fathers, but in many other instances where it may be affected. We are not robots!

Something everyone agreed on was the importance of raising awareness of the issue: of how maternity – and paternity – affects researchers’ careers advancement. Something we hope to have achieved with this round table, and to continue with daily conversations with our colleagues.

“Both career and motherhood have something in common: they accompany us throughout life. We need not to choose one or the other, but to know how to live with both in balance”

Participant (female postdoc and solo mum of 3 teenagers)

You can see the whole round table video in our Youtube channel.

You can also look at this twitter thread for some highlights.

If you would like to support Mothers in Science, you can become a member and join an amazing community of mothers in STEMM.