This week has seen the final conference of ORION (Open Responsible Research and Innovation to further Outstanding KNowledge), a 4-year European project which started in May 2017. Coordinated from the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) and with nine partners – three in Spain, two in Czech republic and one in Italy, England, Germany and Sweden – and a total funding of just over 3 million €, its overall aim was to open up the way life science research is funded, organised and conducted.

Open Science is not a new concept. With Open Access – the free availability of scientific publications by anyone – as its first pillar, back in the early 90s, it has in the last decade moved far and beyond results publication. Open Science refers to opening up (i.e. making it publicly available, free and easy to access) all the steps of the research cycle, from the decision on the research question to the scientific publication of the results and dissemination to broad audiences.

Open Science refers to making all the steps of the research cycle, from the decision on the research question to the publication of the results, publicly available, free and easy to access by both the scientific community and the public.

Opening science: from the scientific community to the general public

We can look at Open Science from two perspectives: the scientific community itself, and the general public.

- The scientific community benefits from it by sharing research data so that it can be used by other researchers from different points of view, and get more out of it; and by having access to other researchers’ results that could inform your own research. This ‘branch’ of Open Science includes Open Access, Open Data, Open Methodology, Open Source or Open Format, among others.

- When talking about Open Science from the general public point of view, we can think of Citizen science, Public dialogues or other forms of public engagement. The public benefits from this by being involved in the scientific process, having a say on how public money is used in research and becoming more scientifically literate.

Both branches of Open Science have gained central stage in recent years.

Within the scientific community, the change has been slow. Science has become, perhaps counterintuitively, more and more closed, due in part to specialization, hypercompetition and the closeness of the publishing empire. The opening up will only be possible if all stakeholders – policy makers, funders, publishers, institutions, researchers – work together for a cultural change. But the movement is unstoppable. Since 2016 the European Commission has given a big push to Open Science, for example with the creation of the European Open Science Cloud (which provides resources on Open Science) and, more recently, the Open Research Europe platform for rapid, free and transparent publication of the projects funded by the EU, which is now compulsory.

The opening up of science will only be possible if all stakeholders – policy makers, funders, publishers, institutions, researchers – work together for a cultural change.

From the public perspective, the involvement in the scientific enterprise is still a bit of a cult matter. But recent developments such as artificial intelligence or genome editing, have created a lot of public debate. Perhaps the Covid-19 pandemic, which has put science in the media spotlight as never before, will be the last push to get the general public more interested in research.

Michela Bertero, head of the CRG’s International and Scientific Affairs Office, was the project coordinator for ORION. According to her, “Open Science is science by definition”, and this opening up is needed to ensure science is “a common value for everyone”. We talk to her about the challenges for the adoption of Open Science and what ORION has achieved in these four years.

“Open science is science by definition”

Michela Bertero (CRG), ORION coordinator

What was the main focus of ORION and how was it organised?

ORION was focused mainly on opening science to society, rather than within the scientific community. It consisted of 6 work packages, each of them led by one of the partners.

During the preparation phase – the first year – we did an internal analysis and a survey with about 6,000 people (1,000 people in each country). The latter was a phone interview to check their attitudes regarding science and medicine, scientific engagement, etc. From this we published a paper reflecting on the different motivations for engagement.

The second and third parts were the core of the project.

The second package included multiple co-creation activities, carried out as “experiments” to understand what works and what does not work in citizen engagement. We also launched a call for new citizen science projects, and we funded two projects:

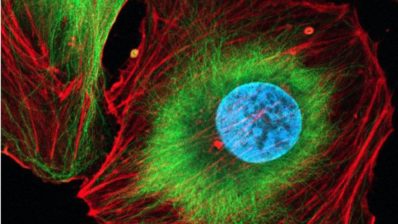

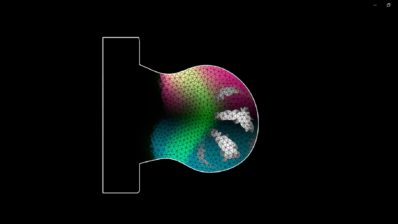

- Genigma, led by the CNAG-CRG, which has co-created an app in which the public can help analyse the differences between cancer and normal cells by playing a game.

- SMOVE (“Science that makes me move”) a project led by the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in which school pupils and scientists worked together on an epidemiological study to record physical activity and sedentary behaviour.

A second, external, call aimed to expand the reach of ORION beyond our team. It was meant for different stakeholders (including researchers, but also schools, local residents, companies, etc) to come together and present new ways to make science more accessible and participatory. From here, two projects were funded:

- VirusFighter, a digital game to explain to students the importance of vaccination, in the UK.

- MELTIC: co-creating and developing ICT health services with stakeholders including local residents of rural areas, in Spain.

The third work package was on training. We created a lot of resources, all of them freely available, either at the project’s website or through open access platforms such as Xenodo:

- a MOOC online course on Open Science in Life Sciences

- a train-the-trainer course on Open Science

- a podcast series on Open Science

- several workshops

- several resources such as case studies, fact sheets, etc.

Finally, an important work package was evaluation, and we have now reviewed all the activities we have done and reflected on all we have learned… We have created a couple of videos about this and in our final conference on September 27th we shared experiences and debated on how to advance at the level of Open Science policies at the institutional, national and European level.

That’s a lot of projects within a project! What has been, for you, the major contribution of ORION?

I think that, beyond all the activities that have been done, the major legacy of the project has been the changes that have taken place at the level of each institution. Two of the partners are funding agencies, and they have done a tremendous change in favour of Open Science practices, creating an action plan on OS and RRI (responsible research and innovation) that they are committed to follow, even after the project is finished. Similar changes have been happening also in the participating research institutes.

“The major legacy of the project has been the changes that have taken place at the level of each institution”

Of course all the material created is open for everyone, so we hope this can also help others who want to do something similar. For example, we have published a ‘co-creation’ menu as an aid to those who want to organise an open, participatory activity.

Another lasting effect of the project is the networking amongst the partners, which we hope will lead to new collaborations.

Finally, we are writing a paper where we present ten general reflections and some of the examples of public engagement activities we have experimented with, at the different levels of involvement in the scientific enterprise: inform, consult, collaborate, empower.

What about at the level of the CRG – what has the centre learned from the ORION experience?

One good output from ORION for the CRG has been the visibility that the centre, and OS in general, has gained. It has also allowed us to gain funding for new projects, such as the citizen science project Genigma, which in turn has brought about a big cultural change on the participating researchers regarding the co-creation process. And internally, we have strengthened the collaboration between the communications department and our scientific affairs office, which were the two departments actively involved in the project.

Also, one of the activities we did at the centre level was a public dialogue about the research taking place at the CRG. Because of the pandemic, it was online, but that also meant we could include people from all over Spain. We invited the general public but also other stakeholders – ethical experts, medical doctors, journalists, industry representatives… We presented several case studies, research projects that are representative of the type of research we do at the centre, and there was a fruitful discussion about the role of basic research, about science funding, about how to communicate science and about ethics. The conclusions of the dialogue will be available shortly on the CRG website.

“We did a public dialogue about the research taking place at the CRG, with different stakeholders, which led to the inclusion in the CRG’s strategic plan of a pillar on open and responsible research”

It was an interesting experience, and it led to the inclusion in the CRG’s strategic plan of a pillar on open and responsible research. We hope to have a second public dialogue soon, this time to discuss the new priorities of the centre such as medical genomics, artificial intelligence… We will need funding, because it’s an expensive activity (all participants are paid for their time and contribution) and now the ORION funding is finished. But we have learned the methodology and also some important lessons. One of them is that the ethical perspective is something we need to reinforce within our scientific community, and that‘s why we have started to organise some seminars on research ethics aimed at our scientists.

Regarding the involvement of the public in research, how far do you think we should go? Should the public be involved in setting the research agenda? Isn’t there a risk that fundamental science projects would suffer compared to more applied ones, which are seen as more ‘useful’ by society?

I believe it really depends on the type of research. With very basic research, such as the one we do at the CRG, one of the most important inputs from society is the reflection on the ethical and social implications of the research. But at the end of the day, with such technically or scientifically complex issues, the priorities have to be defined by the scientists themselves. When the research is more applied, more translational, then it does make much more sense to have a wider influence of the public – for example, patients deciding some aspects of the disease that are important to study that the researchers might not be fully aware of.

Although this was not a main part of ORION, you are very much involved in Open Science at the level of the scientific community. What is in your experience the scientists’ take on Open Science – what are the obstacles for scientists to embrace these practices?

I think that scientists in general are in favour of the Open Science values; sharing is something all scientists agree with, especially younger ones. A few years ago nobody even knew what OS was, and now everyone has at least some idea and they are mostly in favour, although it depends a lot on the discipline. Some fields are more advanced – for example in genomics there are plenty of repositories and resources to make results open – but others are a bit behind, because it’s more complicated or there’s less history.

“I think that scientists in general are in favour of the Open Science values, but some fields – such as genomics – are more advanced and have more resources to make results open, while in others it’s more complicated”

If we look at Open Access, it is increasingly present everywhere. There’s Plan S, and the European Commission is giving it a big push, with Horizon Europe (the new EU research & innovation framework programme for 2021-2027) asking for immediate free access to all results of the projects it will fund. At the CRG more than 80% of the articles published are now open access – but it’s worth noting that this also comes with an increase of the cost, and funding agencies should take note of that! Agreements are being signed to facilitate this OA publishing (for example, Spain signed a transformative agreement with Springer and Elsevier, two of the main scientific publishers), but there’s still issues to solve.

And if we look at data, it’s even more complicated. Funding agencies are starting to expect everyone to create Data Management Plans (DMP), to make their data FAIR. This is great, but it needs a lot of resources, expertise (data managers), etc. which are still not widely available. At the CRG we have a policy for data management and at the moment we are developing guidelines to bring that policy to reality with a research data management board formed by people with different expertise – technological, legal, IT, policy, training, core facilities… It’s not easy, but it’s the way to go.

Regarding the scientists at the individual level, the reasons to not embrace OS practices might be varied. For one, as I mentioned it requires time, money, infraestructures and knowledge. But there’s also, potentially, fear – of being scooped, of someone else using your data and publishing before you. With preprints this can be partly solved, because many journals now accept them as a record of priority, so scientists are starting to make their data available in parallel to their publication as a preprint, prior to its publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Another important point that makes scientists reluctant regarding OS are the incentives. We are currently incentivising (via evaluation for funding) the competition to publish in high Impact Factor journals, rather than the sharing of data. We can’t expect scientists to embrace Open Science while the evaluation system doesn’t change.

“We are currently incentivising competition to publish in high Impact Factor journals, rather than the sharing of data. We can’t expect scientists to embrace Open Science while the evaluation system doesn’t change”

Then at the level of the institutions, there’s the challenge of technology transfer and creating commercial value in an Open Science environment where these results are open and free for everyone. This challenge means some people that have a potential product are less likely to share their data. But there are examples where this conflict between sharing and commercialising has been solved, like Nextflow, an open source software developed at the CRG and available for free, where two spin offs have been created that offer specific services to companies. One of these spin-offs, Seqera, has actually just raised 5.5 million euros – which shows that sharing data or information doesn’t need to have a negative impact on your success!

So now that the project is finished, what next? How do you see the future of Open Science?

I believe the area that needs more development will be data science – how to share and find the data, how to integrate different types of data… That’s going to be a big challenge.

For the mid-term future, as a colleague of mine says, in 5-10 years we won’t talk more about Open Science, because the ‘open’ part will be obvious. It will be the ‘normal’ science, in the same sense we should not talk about ‘ethical science’ because all science should be ethical.

You can find all the ORION resources in this website.