It has been long proven that the microbiome has an impact on human health: on cognitive capacity, prevention of alcohol addiction, response to vaccines, among others. This is why there are many groups within the scientific community dedicated to studying the bacteria that inhabit us. But how do we acquire them?

This is what a recent international collaborative study led by the University of Trento has sought to explain. Mireia Vallès-Colomer is the first author of the study and she will soon join the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB) as principal investigator of the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences of the Pompeu Fabra University (MELIS-UPF), where she will continue working on the microbiome.

Studying the microbiome transmission

Unlike with the COVID-19 virus, when we learned about its transmission in record time, we do not know much about how the bacteria in our microbiome are transmitted. Nevertheless, the importance of the microbiome is such that we humans couldn’t live without it.

To carry out this study, the research team had access to public data that includes more than 9,700 oral and faecal samples from individuals from more than 20 countries on 5 continents. In addition, some of these samples are from family members, which has allowed the scientists to study transmission in this type of relationship. And thanks to new high-resolution metagenomic tools, they have been able to carry out a precise study of microbiota transmission.

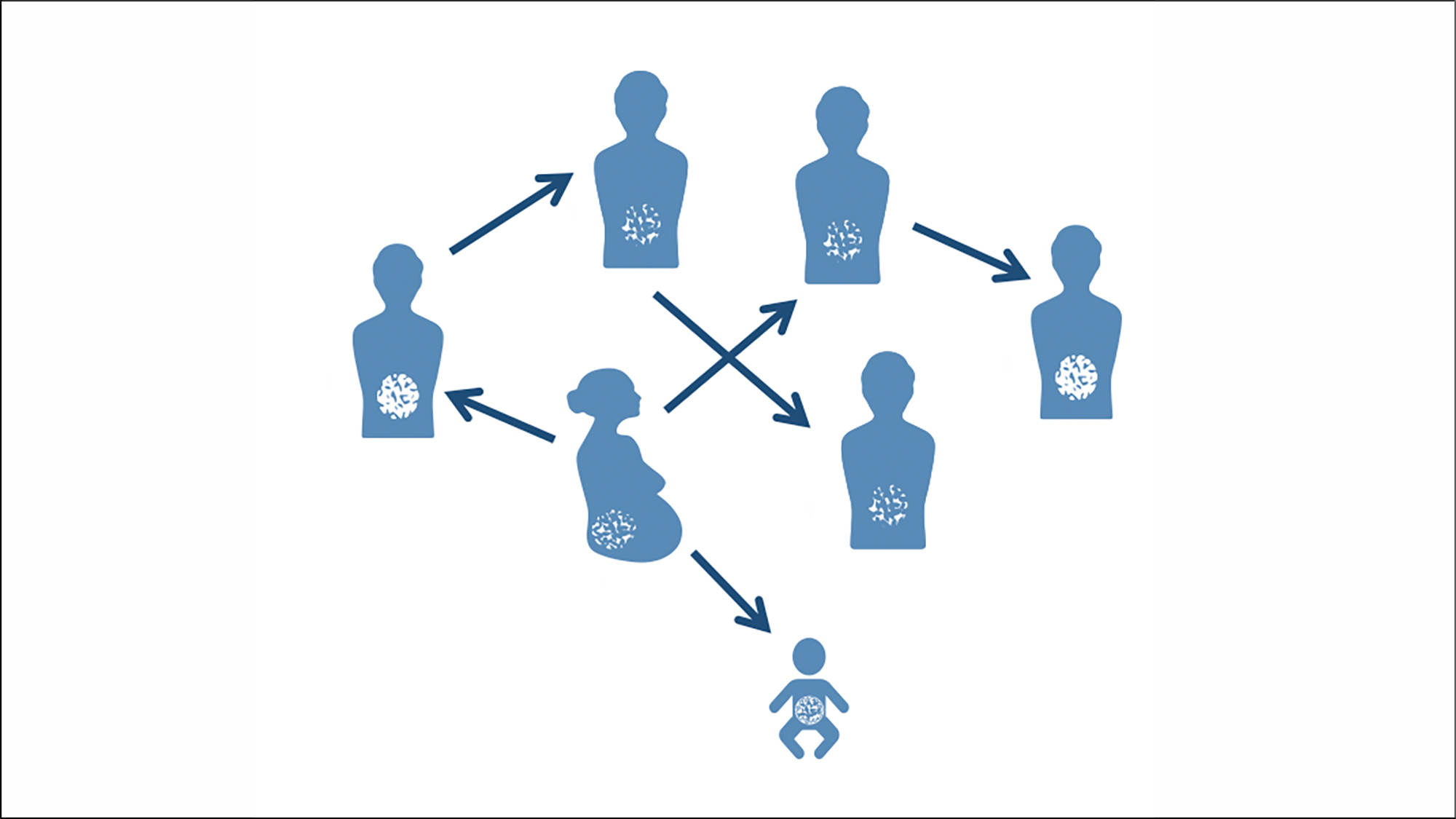

Vertical transmission, the transfer of bacteria between mother and child at birth, had been studied before – and the team was able to see how different types of labour (natural or caesarean section) affect this transmission, with lower transmission resulting from C-section. But babies do not have many of the bacteria typical of adults, which led the researchers to believe that there must be also horizontal transmission later on. With this study they have been able to prove it.

Gut and oral microbiome

The gut microbiome is more complex than the oral microbiome (the one found in our mouths) and its influence on gut diseases and even mental health has long been known. Compared to the oral microbiome, it is more densely populated, with more than 1,000 species already known – and even more yet to be discovered!

This study has shown that, at birth, babies share up to 50% of bacterial strains with their mothers. But from the age of one year, this percentage starts to decrease to 34%, and decreases even further with age.

In adults, it seems that the gut microbiome is influenced by cohabitation (people in the same household share 12% of strains, regardless of their relationship) and by the individual’s social interactions (people in the same village, for example, share 8%). Thus, explains Mireia Vallès-Colomer, “the transmission of intestinal bacterial strains also seems to occur between individuals who live nearby but do not cohabit, representing the social relationships of the host population”.

The species that are part of the oral microbiome are different from those in the gut. As they use saliva as a vehicle of transmission, they are usually more aerotolerant. However, not all oral bacteria are transmitted in the same way, and transmission has not been found to be linked to their prevalence or abundance. They have also observed that mother-baby transmission is not that strong in the case of the oral microbiome. However, it was found that the exchange of strains depends mainly on the duration of contact.

“Our study shows that social interaction promotes the exchange of the microbiome between adults”

The role of social interactions in microbiota transmission

Although much remains to be discovered about the microbiome and its transmission, the scientific community hypothesises that a more diverse microbiome is a good thing, because the more diverse, the more resilient to the perturbations we may suffer.

This research has shown that adult individuals who have close contact with each other share part of their microbiome, reinforcing the hypothesis that “diseases that we nowadays consider non-communicable, such as cancer or heart disease, could have a transmissible microbial component“, explains Vallès-Colomer. It also opens the door to new studies that analyse patients’ social interaction networks to find out the degree of transmissibility of their microbiome and the diseases they suffer from.

Valles-Colomer, M., Blanco-Míguez, A., Manghi, P. et al. The person-to-person transmission landscape of the gut and oral microbiomes. Nature 614, 125–135 (2023). doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05620-1