Nowadays, culturing cells in vitro is a routine protocol in most bioscience laboratories in the world. Widespread use of in vitro cultures has reduced animal experimentation and has led to a number of important discoveries in genetics and disease modelling, cancer and stem cells, or production of antibodies and other specific proteins. But this revolutionary technique was established just over a century ago.

Improvements in media, devices, protocols and equipment have given today’s researchers the possibility to culture cells from almost every tissue and species. The more recent 3D culture technologies have allowed to mimic small organs in 3D, co-culturing different cell types in vitro or perfusing cellular structures to resemble their physiologic conditions. But to break frontiers, science needs to go beyond traditional methods and give free rein to creativity.

To enable this step forward in biological applications, the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB) has just opened a micro-Fabrication Laboratory (µFabLab), a place where ideas can be realized thanks to the fabrication of simple prototypes.

A multi-centre initiative

This project was promoted by Kristina Haase, group leader and bioengineer at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory – Barcelona (EMBL Barcelona). When she joined EMBL, she wondered whether there was a place in the building to fabricate new tools. “Our group routinely designs and generates microfluidic devices, but we want to expand to a high-throughput-scale and to integrate complicated circuitry for control and sensing on-chip”, says Kristina. Although this type of place did not exist locally, “EMBL and CRG scientific directors, James Sharpe and Luis Serrano, together with Oliver Blanco, the PRBB infrastructure’s manager, were super excited about the project and pushed it forward”, explains Haase.

The PRBB is a crowded building where each square meter is occupied by laboratories, offices or meeting rooms to enable scientific advancement. That is why “the first challenge was to find some space to build the µFabLab”, says Oliver Blanco. “We had to be creative and we ended up converting an old warehouse in the -2 basement floor into an ISO 8 cleanroom. That’s like having a clean labor room, where children are being born, next to a dirty parking lot!”, he explains. On top of that, they had to fill the room with all the general installations of water, electricity, air conditioning, technical gasses, etc. so that the space could be functional.

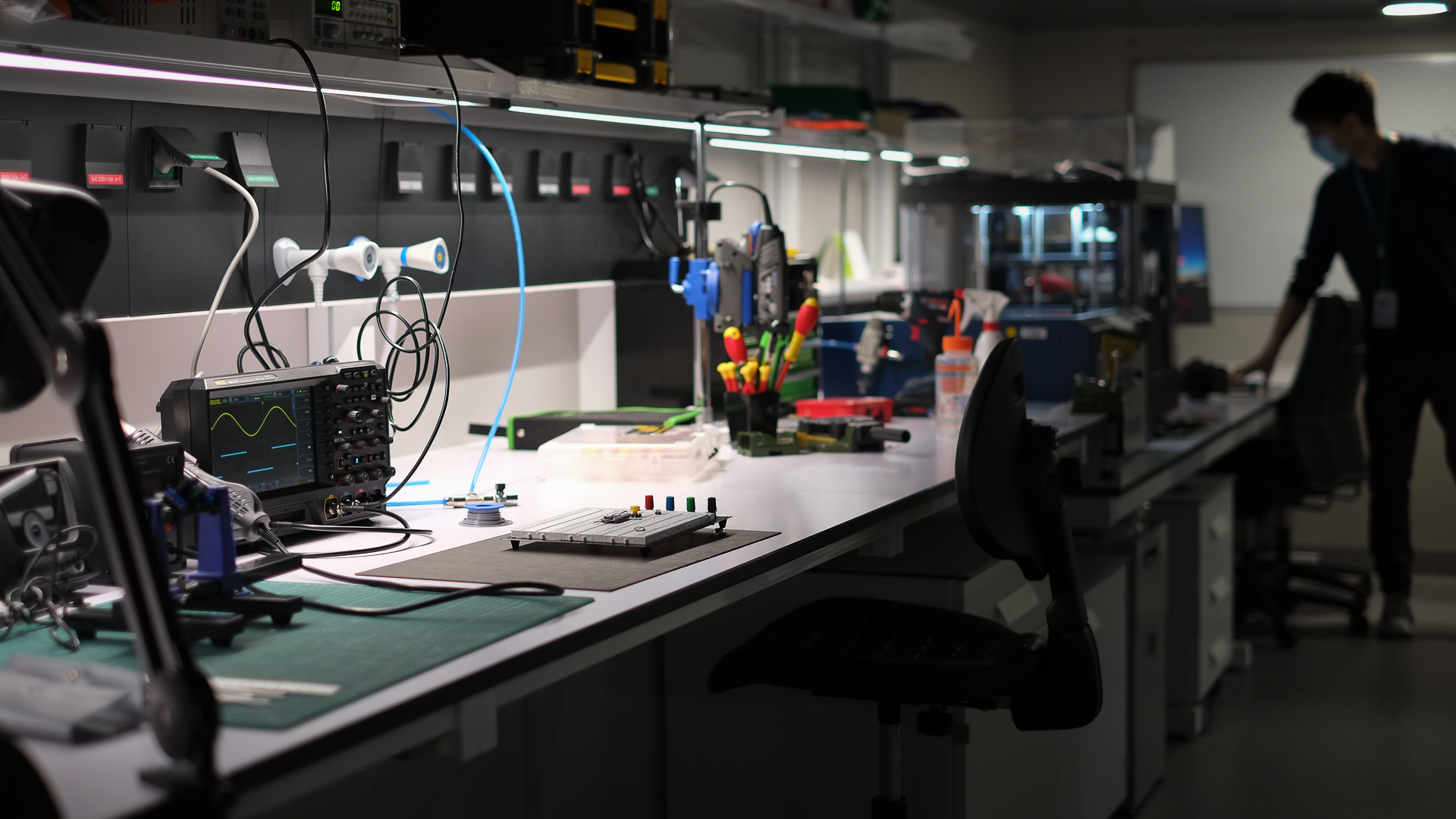

Now that the lab is built, the different centres at the park, including EMBL, CRG and UPF have filled the space with equipment to fabricate small prototypes. Among them several stand out:

- two 3D printers, one for multi-material printing of thermoplastic filaments and another for printing of bio-compatible resins;

- a small CNC machine that works by milling of plastic or soft metal blocks to produce the desired prototype by removing material in a precise manner from a workpiece

- an electronics bench to generate small controllable or automated prototypes.

Besides, scientists working at the lab will have the capacity to build PDMS-based microfluidic devices using spin coaters, a plasma machine and other related equipment.

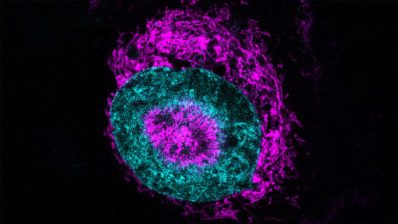

This range of equipment will allow scientists to “recreate complex 3D physiologic-like microenvironments to study tissues, or to make entirely new environments in order to investigate biological questions in a controlled manner”, explains Haase.

A matter of trial and error

The key for ensuring the success of the µFabLab is having Roberto Paoli, a technical specialist from EMBL Barcelona, as a manager of the lab. This engineer by training, who has been combining fabrication with biomedicine for years, is convinced of the match of these two disciplines. “When you explain to biologists how a technology can help them, they start coming up with new, great ideas that they didn’t even imagine were possible”. That is why, Paoli will be in charge of training local personnel in use of the technology and will also hold demos to introduce rookies to the microfabrication world.

“This facility will enable us to prepare microfluidic devices for the study of an in vitro reconstituted microtubule cytoskeleton in micron-scale environments, mimicking the situation in the cell”

Thomas Surrey, PI at CRG

Besides, “a good thing about rapid prototyping is that it enables you to rapidly design, fabricate, and iterate on your model. So you can quickly test your first prototype to see what is working, what is wrong, and where to improve it”, says Paoli. That is why the PRBB community is excited to integrate microfabrication in their current research projects.

“The microFabLab will be relevant for UPF researchers working at the interface of tissue engineering, synthetic biology, nanotechnology or genomics. We expect to develop highly innovative projects now that we will have this infrastructure in the building”

Berta Alsina, PI at UPF-MELIS

Beyond prototype fabrication

According to Nicholas Stroustrup, PI at the CRG, “the new fab lab will not be merely a space to store valuable fabrication equipment or even develop prototypes. Rather, it will be a hub through which members from diverse institutes and scientific backgrounds interact to share practical advice and build a community of expertise”. That is why facility managers from the PRBB and the institutes are devoted to “provide scientists the needed infrastructure and a correct service of maintenance so that they can develop their research activities”, adds Eugenia Silva, head of Facility Management at CRG.

We hope in the coming months the first prototypes of microfluidic devices, small tools for 3D culture, cell holders or complex chips with integrated sensors will come out of the PRBB’s brand new microfabrication lab.