Russ Hodge has a fascinating job: writing stories about science. With no previous scientific background, other than some amateur astronomy and archaeology, he started up the European Molecular Biology Laboratory – Heidelberg (EMBL) press office, created a programme for teachers and obtained funding for the teachers’ magazine Science in School. Now at the Max Delbrück Centre in Berlin and with more than 20 years of experience, Hodge came to the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB) to help scientists develop their communication skills through a course from the park’s ongoing-training programme, Intervals.

How did you get into science writing?

I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was 6 and when I got to university I studied psycholinguistics, to pursue the structure of language and how the brain deals with meaning. Then, when I was in Heidelberg teaching students to write in English, many of them happened to be scientists. Juan Valcarcel and Thomas Graf, currently at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), were my neighbours and when a position came up at the EMBL to write about science they told me about it. I applied and somehow got the job!

What was it like at the beginning?

It was 1997 and the communications department was being created. I had to write an annual report and after looking at other examples, decided to do something new, using “storytelling” because that’s what I knew! But it was clear I needed to understand the science before I could write about it. I was exposed to a wide range of science and I had a knack for uncovering the thought processes behind it. Still, it took me three years to be able to read a scientific paper without asking the author a million questions about it!

What are the challenges of science communication?

Many young scientists in Europe never write anything until their first paper or dissertation. They tend to get lost in the details and not see the big picture; they lack clarity. When they talk to outsiders, their explanation is full of ‘ghosts’ –concepts and models that give everything in science meaning, and which are so obvious to scientists that no one bothers to explain them. Imagine having to learn chess just by watching people playing, without knowing the rules! It’s similar when trying to understand science with no context.

Many scientists tend to get lost in the details and not see the big picture; they lack clarity. When they talk to outsiders, their explanation is full of ‘ghosts’ – concepts that give everything in science meaning, and which are so obvious to scientists that no one bothers to explain them.

How can scientists best explain their research?

First they need to understand the way they think about something themselves, by remembering the way they learned it, or visualising the “molecular world” they imagine. They need to form a clear idea of what their audience knows and be able to recreate a story in a minimal way. It’s often possible to find a pattern in the audience that’s similar to a scientific model or structure. This allows the scientist to see different aspects of the system and ask different questions about their own view.

So science communication can be good for scientists?

Absolutely! Talking to lay people can give scientists new ideas. I’ve been trying to convince researchers for years that they should not just do science communication ‘if they have time.’ They really need to communicate with the public because it forces them to see their own work through new patterns, and this can be extremely helpful.

Any tips?

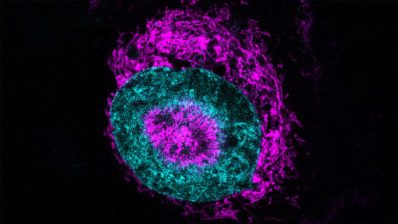

The first thing is to articulate a precise research question. Uncover the visual metaphors required to explain it. Then distance yourself from it, and look at things in an abstract way. Try to put yourself in the position of a molecule within a system and ask what’s there in its environment to interact with and what forces are acting on it.