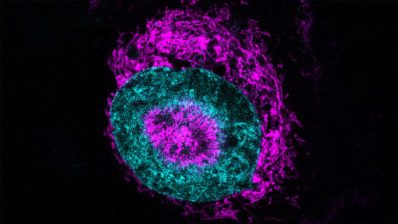

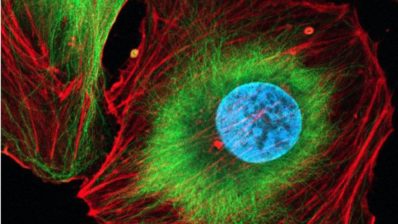

Maria Lluch was one of the firsts graduated from the biotechnology degree at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB). Since, she has dedicated her scientific career to studying one of the smallest bacteria that exist, only 0.2-0.3 µm in diameter: Mycoplasma. We would need to put about 70,000 of these bacteria in a row to make the diameter of a five-cent coin.

From Mycoplasma genitalium to Mycoplasma pneumoniae

After focusing her research on Mycoplasma genitalium as a minimal organism model during her PhD, when she arrived at the laboratory led by Luis Serrano at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), Lluch started to work with Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

“Understanding how a genome as small as that of Mycoplasma works is key for designing models that allow predicting how genomic changes would impact the physiology of any organism”

But why study Mycoplasma? Due to its size, the genome of these bacteria is very small, facilitating their study. If one understands how these organisms work, in the future one could design computational models that allow predicting how a change in the genome would impact the physiology of any organism.

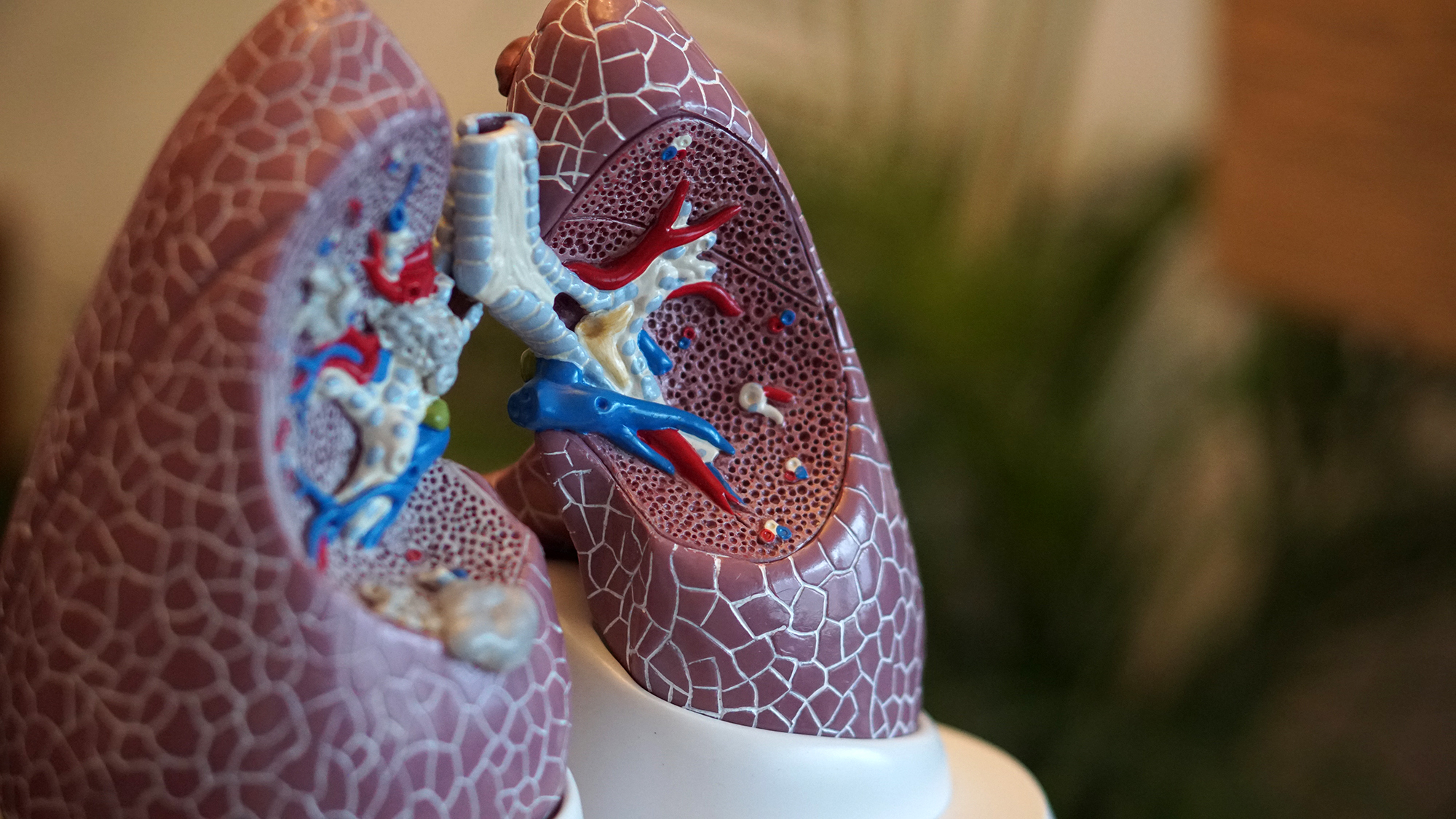

In this direction, Lluch’s postdoc focused on understanding the biology of M. pneumoniae, a mycoplasma that, located in the lungs of the majority of the population, is associated with typical pneumonia. At the end of her postdoc and starting as a Staff Scientist (associate researcher) in the same CRG laboratory, Lluch had the opportunity to follow her own line of research, focused on synthetic biology. The objective: to develop tools that allow modifying the genome of M. pneumoniae thanks to the knowledge obtained studying its cellular biology.

A bacterial chassis to treat diseases

“Imagine a car where you remove the body, and only leave the chassis and the essential parts (engine, wheels …) to keep it running. Well, the idea was to do the same with M. pneumoniae” the CRG researcher explains. “We sought to create a safe and attenuated bacteria strain by removing all the elements that could cause any pathogenic effect, and thus be able to use the bacteria as a therapeutic vehicle. A vehicle that reaches the target tissue and produces and secretes heterologous proteins, that is, proteins obtained from expressing genes not characteristic of M. pneumoniae“, Lluch adds.

“We sought to create a safe and attenuated bacteria strain by removing all the elements that could cause any pathogenic effect, and thus be able to use the bacteria as a therapeutic vehicle.”

Maria Lluch

The first disease that the researcher and her colleagues in the laboratory tried to treat was ventilation-associated pneumonia. It is a pneumonia that affects intubated ICU patients, very vulnerable to infections caused by pseudomonas and staphylococcus, which are pathogenic bacteria that adhere to endotracheal tubes, where they form very thick biofilms and are difficult to eliminate with antibiotics. The idea is that M. pneumoniae, taking advantage of the fact that it can reach the lung because it is its natural habitat, can target these biofilms and produce agents that pierce them continuously and locally.

MycoSynVac, or how to design multivalent vaccines for animals

With this idea of bacteria as chassis, Luis Serrano’s laboratory started the European project MycoSynVac with the aim of protecting animals from infectious diseases caused by viruses and bacteria, at the same time. The way to achieve this was to create multivalent vaccines, which provide protection against various pathogens, in a single molecule. The bacteria used as the chassis in this project is a strain of M. pneumoniae, modified so that it can express surface antigens against certain animal pathogens.

Although the MycoSynVac project ended in April 2020, trials are still ongoing to determine the degree of protection of the vaccine, as well as to study its dose-response and pharmacokinetics. “Thanks to the project we know that, in animals, the vaccine generates an immune response against three different pathogens. We are currently analyzing its degree of protection. That is, if when the animal is infected by the pathogen, there is an immune response good enough to combat the infection” Lluch says.

Proving in animals that the bacterial chassis is safe and that, at the same time, the surface antigens that it expresses generate an immune response, is very useful since, at the same time that this vaccine works in animals, the results obtained from this project are useful as a source of information for the design of future human applications.

From MycoSynVac to Pulmobiotics

With the idea of getting started in human applications, Lluch, together with Luis Serrano, has inaugurated the Pulmobiotics company. Their aim is to develop therapeutic applications to fight lung diseases.

“Pulmobiotics is based on all the knowledge that we have been developing over the years in terms of molecular tools, creation of attenuated strains, production of proteins of continuous secretion to treat lung diseases…”, says the researcher.

“The death of patients intubated in the ICU is not only a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, but secondary infections caused by the fact that they are intubated. At Pulmobiotics we plan to orient our product, in part, to the treatment of COVID-19.”

The beginnings of Pulmobiotics have not been easy, since its launch has coincided with the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, as it is a company that seeks to find solutions to lung diseases, Lluch and her team plan to temporarily reorient the objective of this CRG spin-off.

“The death of patients intubated in the ICU is not only a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, but secondary infections caused by the fact that they are intubated. At Pulmobiotics we plan to orient our product, in part, to the treatment of COVID-19“, Lluch explains. “The expression of nanoantibodies that recognize and block the virus, the exposure of surface antigens against the virus in attenuated bacteria to obtain vaccines… These are different strategies that we are considering to fight against the current pandemic”, the researcher adds.

“When you look at the top 10 causes of death worldwide, lung diseases are among the first. I think we have the opportunity to develop a technological platform that will allow us to treat various diseases. That is, now we will focus on pneumonia associated with ventilation, but thanks to synthetic biology we can obtain, relatively quickly and easily, modified bacterial strains that serve to treat other pulmonary affections. Our idea is to focus now on a specific product and, perhaps, develop treatment alternatives to combat the current pandemic of COVID-19″, the co-founder of Pulmobiotics concludes.