Elena Hidalgo and José Ayté were in Boston when they saw an ad in Nature about a position at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra’s new faculty of Health and Life Sciences (DCEXS-UPF), in Barcelona. Sixteen years later, they share a 15-strong research group at this university, where they use the same model organism – the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe – to study two topics: oxidative stress and cell cycle control.

The role of ROS in ageing: harmful or beneficial?

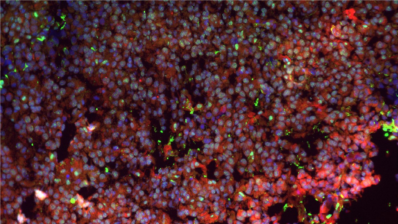

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) are very unstable molecules that contain oxygen and are constantly generated within our cells as a side effect of respiration, the metabolisation of sugar in the presence of oxygen. “Respiration is much more efficient, energetically speaking, than fermentation“, explains Hidalgo, but the flipside is that ROS are produced as side-products. These are toxic because they interact and may harm proteins, lipids or DNA. The group is currently studying how oxidative stress disrupts proteostasis, or the protein maintenance system in the cell. This concept is central to diseases associated with excessive protein misfolding or aggregation, such as Huntington’s, Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s.

“Respiration is much more efficient, energetically speaking, than fermentation, but ROS are produced as toxic side-products and they may harm proteins, lipids or DNA.”

Elena Hidalgo

To deal with ROS, cells display potent antioxidant systems. And it is good to let them fight, states Hidalgo, who is studying how cells sense that stress and how they respond. Calorie restriction and exercise physiologically increase ROS levels. This may seem a bad thing, but it actually forces the cell to activate routes that lead to repair, as well as produce antioxidants to decrease ROS. Her group has shown that when yeast cells are grown with high levels of glucose they die two days after reaching the stationary growth stage. Yeast cells grown with reduced glucose suffer more initially, due to a lack of nutrients, but once at the stationary stage they live until day 10 at least.

“Calorie restriction is beneficial for chronological ageing. Something similar was seen in an important experiment on humans and exercise”, she continues. People were told to exercise, exercise and take antioxidants, or rest. Those that rested had higher levels of ageing markers, but so did those who exercised and took antioxidants! This is because exercising increases ROS, which push the cells out of their comfort zone; that is why endogenous oxidative stress can be good. But taking external antioxidants removes the ROS without the cells doing anything at all; “it robs them of their chance to fight and get fit”, explains Hidalgo.

Calorie restriction and exercise physiologically increase ROS levels. This may seem a bad thing, but it actually forces the cell to activate routes that lead to repair, as well as produce antioxidants to decrease ROS. (…)

START

The other half of the lab, led by Ayté, focuses on cell cycle control. There is a point during the cell cycle called START, when cells have to decide whether they commit to mitosis (cell division), meiosis (the specialised division that gives rise to sporulation in yeast), or quiescence. START is totally conserved in all eukaryotes and is known as a restriction point in mammalian cells. Inactivation of this restriction point leads to unregulated cell cycle progression promoting uncontrolled cell growth, genomic instability and aneuploidy, hallmarks of tumour progression. “To divide, cells must first duplicate their DNA and we have identified a protein, Yox1, which ensures that the DNA has been properly copied before the cell enters mitosis”, explains Ayté.

He, too, uses fission yeast to study the link between oxidative stress and cell cycle progression. When the main pathway controlling oxidative stress, that of the MAP kinase Sty1, is mutated, cells cannot survive in the stationary phase and they display cell cycle defects. Ayté’s research is aimed at determining how oxidative stress impinges on the regulation of cell cycle progression. “Oxidative stress and cell cycle have many connections, and we currently have overlapping projects between the two topics”, conclude the two group co-leaders.