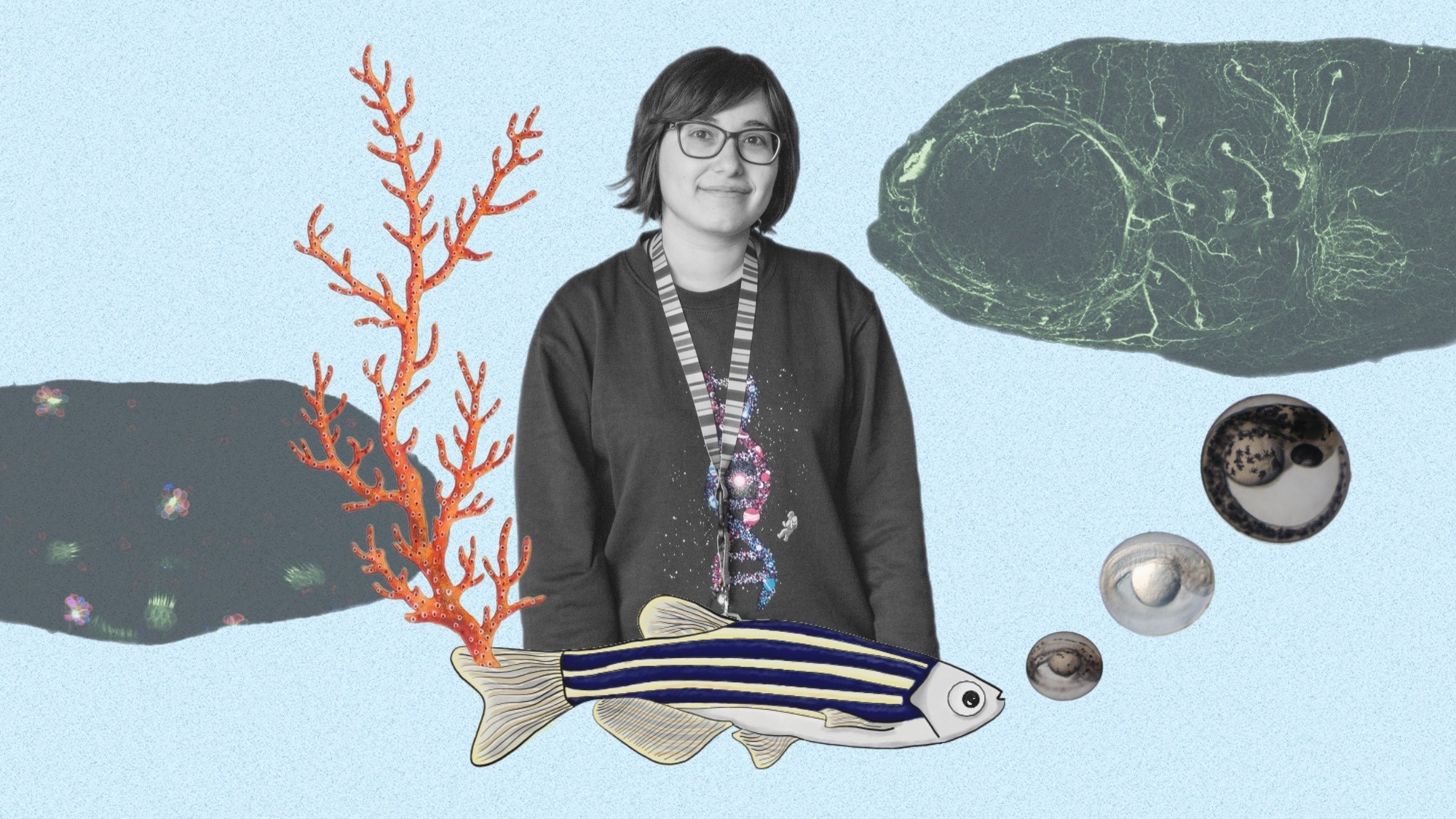

Nerea Montedeoca Vázquez is a doctoral researcher in the Morphogenesis and Signalling in Sensory Systems group led by Berta Alsina in the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences at Pompeu Fabra University (MELIS-UPF). Her first contact with the team was during her master’s internship. She was very interested in developmental biology and when Berta offered Nerea to do a PhD in her lab, she didn’t hesitate. Now, she has just started her third year.

Nerea’s work consists of understanding the development of the inner ear. To do this, they use the zebrafish as a model organism, because both in terms of embryonic morphology and genetics, this fish is very similar to humans. She is currently working on a model of deafness based on the minority disease Townes-Brocks.

Rare disease funding is needed to ensure the welfare of patients suffering them

Graduated in biomedical sciences, her relationship with rare diseases started during her Erasmus in Amsterdam, where she worked with the disease adrenoleukodystrophy and confirmed her interest in research.

Nerea tells us that there are days when she stays until really late working in the lab, but other days she limits the time she spends there. However, it is difficult for her to leave science aside and she often finds herself at home thinking about what she can do to improve an experiment the next day.

During her free time, apart from relaxing while reading or listening to music, she practices kendo, a Japanese martial art that uses bamboo swords. She also often goes out with her lab mates and they do activities together such as calçotades or excursions, among others.

Do you want to know more about Nerea? Read on! And remember that you can read more portraits of young female PRBB researchers here.

Is a scientist born or made?

It depends. I believe that, in some way, everyone at a very early age is a scientist at heart. Children have this innate curiosity that makes them try things out to test hypotheses. Imagine a baby when they get a toy. They will observe, touch, smell and even taste and bite it. After this, they will probably throw it again and again. Even if it isn’t a conscious thought or process, they begin acquiring knowledge about what’s around them in this way – in the same way we scientists do it, in essence! However, scientists are also made by working hard and learning new things daily. I think both innate and acquired capabilities are essential for a good scientist.

What is your field of study?

My field of study is developmental biology. It’s not easy to come up with a metaphor for describing the complexity of the field but it reminds me a lot of a particular scene from the movie ‘The curious case of Benjamin Button’. The scene I’m referring to is the so-called ‘taxi scene’. Without making any spoilers, the scene tells us how a series of small and seemingly unimportant concatenated events ends up causing a major incident: “If A had woken up 5 minutes before, if B hadn’t forgotten her coat… the outcome would have been completely different”.

That is exactly what developmental biology is about, since both where and when certain events occur affect the formation of an eye, an ear, the brain or the whole embryo. A simple deviation from the standard cascade of events taking place during development can lead to a significant consequence, usually a negative one.

What sparked your interest in science, and in your specific field?

I’ve always been a curious child who had tons of questions about nearly anything. When I was young, I had many science-related careers on my mind: astronaut, astronomer, speleologist, marine biologist… I have ended up working in the developmental biology field. Still, I didn’t realise its true beauty until I came to my current laboratory to work on my master’s thesis.

What kind of student were you as a child?

I’d say I was the typical ‘straight-A’ student everyone knew for being a nerd and a bookworm, although, to be honest, I have always been the kind of person who always starts studying the day before a test, even at university. I have never failed an exam using this strategy, but it is something I do not recommend at all!

What would you be if you were not a scientist?

Probably a graphic designer, a chef or a teacher.

If you could travel in time and work on past or future science, what would you choose?

Although it would be fantastic to meet and work with some of the most outstanding scientists in the past, I would choose the future for many reasons. First, I’d love to know how far science has advanced from today, and I’d be looking forward to contributing. And secondly, I’d like to think that in the future, science will have been freed from all the biases we have sadly been dragging until today: gender, ethnicity, wealth and so on. I wish everyone who wanted to be a scientist could have enough opportunities, regardless of their background.

How would your colleagues describe you?

I think they would describe me as a reserved and quiet person. A bit eccentric sometimes, too, but friendly and always willing to help!

What would you like to add to the phrase “finally solved”?

Until we pose the next question.

What preconceived idea about scientists you think has some truth in it? And which one is totally wrong?

I think that the idea of scientists being a bit crazy might have some truth in it. Many discoveries that have been made until today wouldn’t have been possible if someone hadn’t put their crazy ideas and theories to the test. On the other hand, I believe that the concept of all scientists being serious and boring is entirely wrong. I think I have more than enough sample size to prove it!

What has been your best failure?

Not learning how to say no to others out of fear of disappointing them.

The best advice you have been given.

Don’t let others decide what’s best for you. You should write your own destiny.

Tell us your favourite scientific quote or scientific joke.

I really like a quote from Lewis Wolpert, which is pretty well-known within the developmental biology field: “It is not birth, marriage, or death, but gastrulation which is truly the most important time in your life“.

Who is your favourite scientist and why?

Lynn Margulis. She proposed the theory of endosymbiosis, which at the time was a very radical idea that many scientists refused to give validity to and even ridiculed in some cases. I admire her for her perseverance, strong willpower and for fighting for her ideas despite all the voices telling her how wrong and crazy they were. I believe the world needs more people like her who aren’t afraid of coming up with ‘crazy’ ideas, in science and every other discipline.

Can you please recommend…

a book:

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle from Haruki Murakami.

Music:

Anything from Blaumut.

An artist:

Frida Kahlo and Buster Keaton.

A film or documentary:

Millennium actress from Satoshi Kon.

An interesting YouTube channel:

A digital communication medium on any subject:

‘El descampao‘ podcast.

Thank you so much Nerea and good luck with your thesis!