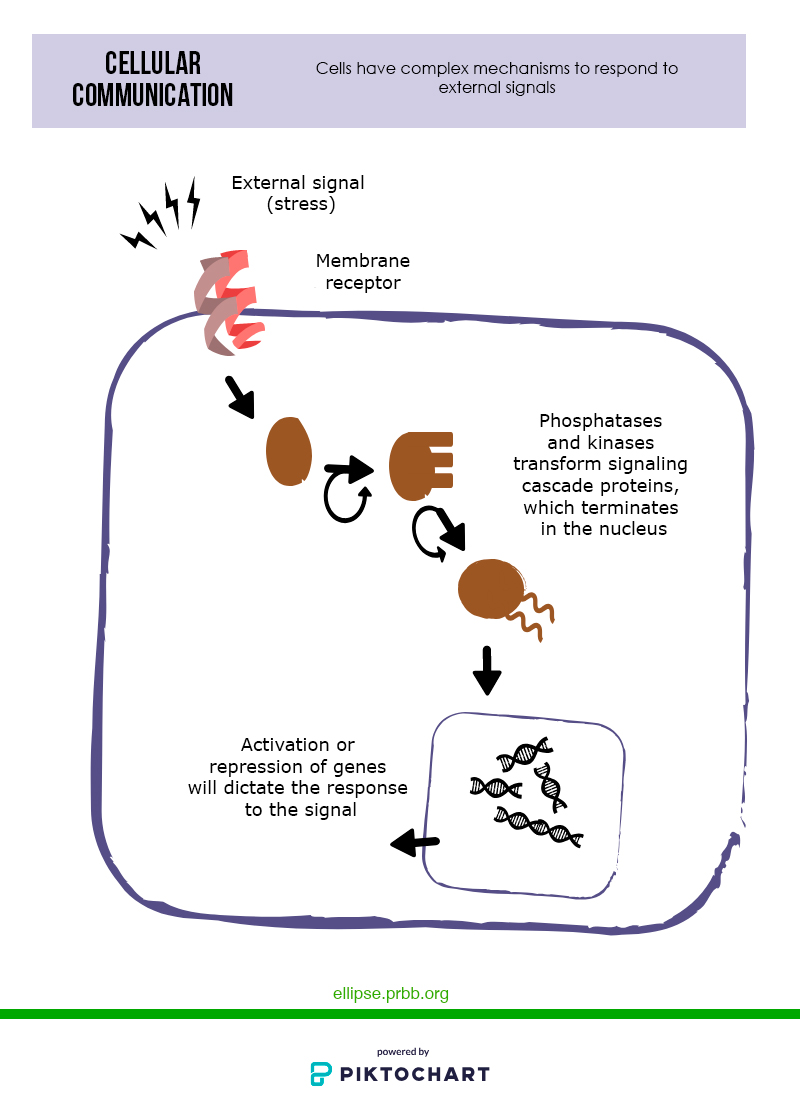

Communicate or die – that’s the law for cells. Cells need to know what is happening in their environment in order to react appropriately at any given moment. That is why they have very complex signalling mechanisms.

Except when the signal is diffusible, signalling usually starts with a receptor located in the cell membrane (the membrane that covers the cell and separates it from the outside). This receptor detects a signal from the environment and consequently it activates a protein, which will activate another protein, and so on. This is called a signalling cascade. In eukaryotic cells, such as human cells, the components of these cascades are usually kinases and phosphatases – two types of proteins that add or remove a chemical group from other proteins, thereby modifying their activity. The signalling cascade ends in the nucleus, the part of the cell where the DNA is located, and will end up activating or repressing specific genes. The action of these genes will dictate the response to the initial signal.

Signals that trigger a reaction in the cell include various types of external stress, such as food deprivation, heat shock, or osmotic stress. The stress signal can also be internal, such as oxidative stress: the use of oxygen during respiration can generate reactive molecules as a by-product, and these can damage other types of biomolecules, including DNA.

In addition, cells also need to talk to each other in order to behave as a whole within the organism. This intercellular (‘cell-to-cell’) communication can be through physical contact or through molecules released by one cell and taken up by another.