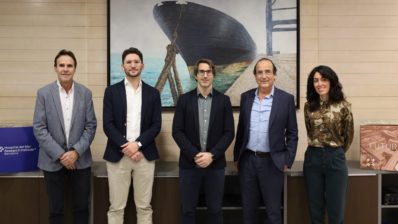

Producing biomaterials and other products from organic matter without creating new waste is the mission of BIOM (Bioinspired Materials). This Catalan start-up—a spin-off of UPF with just three years of activity—has developed two patents and has more projects in the validation phase. We speak with Javier Macía, researcher at the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences at Pompeu Fabra University (MELIS-UPF), co-founder of the company, and current scientific lead at BIOM, to learn more about this emerging company.

How did the idea of creating BIOM come about?

It all started with a personal story. An acquaintance, an architect focused on the construction world, was interested in using biomaterials. One day, while talking about alternatives to cement, we started thinking about polymers and proteins, and it caught my attention.

I told a lab colleague I was working with about it, and he got very excited. So much so that, even though it initially began as a fun exercise without real intention, we started playing with protein blends and achieved some very initial results that seemed quite interesting. That’s when we started to take it more seriously.

What are the company values?

At the beginning, we thought about what we wanted to do with this company and what the objective was. We all easily agreed: we want to improve the world. It might sound a bit nerdy, but at our age, becoming multimillionaires at 30 is not our model. Our idea is to bring solutions to the market that have a positive impact on the environment, a positive impact on the economy, and that are also economically sustainable. We only want enough profit to allow us to do this. You can do things to make money or you can make money to do things; we fit better with the second model.

Was it difficult to transition from the academic to the business world?

It’s not ‘it was’, it still is! It’s difficult because it’s a completely different world. The lab world, the academic one, aims to do research, usually with a paper as your final product. However, when you make the jump to the business side, the requirements are different. There is more pressure; companies need to survive financially, and deadlines are very tight. Time becomes money, and that adds extra weight.

Transfer and industrial scalability also feel quite distant from the lab setting.

“To start a company, you need to change your mindset and step outside of the academic research perspective.”

What’s the hardest part about starting a company?

First, understanding the language of investors; if we spoke in Klingon, the language of the Star Trek aliens, I think we would understand each other better! Just yesterday, I had a meeting with some investors, and I still found it hard to understand them. And what they say can have a huge impact, so you need to change your mindset and step out of the academic perspective.

From a research perspective, you think contributing to scientific development is the most important thing and the rest is secondary. When you enter the business world, you realize that’s not the case: scientific development is part of the story, but there are equally or even more important parts. You may have the best product in the world, but if you don’t have an investor, an industry to produce it, or a solution for industrial scalability, you won’t sell it. Realizing that you are no longer the center around which the sun revolves, but that the sun revolves elsewhere, is a big shift in mindset.

How do you secure funding?

The initial funding came from the acquaintance who had the idea with me. He pulled in some friends, as did we, and we managed to get some initial capital to start. We also spoke with the UPF, which got involved, so we created a spin-off of the UPF.

Then we got public grants, and now we are closing a funding round with a group of venture capital investors that should give us stability for at least the next two years. This is important because we need to complete the entire transfer process to launch the first products in that time.

Returning to your products, can you tell us more about what you do?

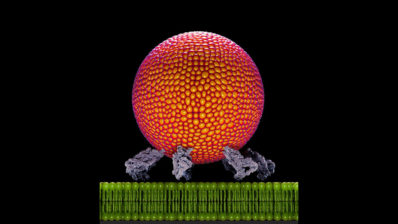

We make products from waste from different industrial sectors, such as manure. And the most important part is that during this process, no extra waste is generated. That is, our production processes mean that 100% of what goes in becomes the product.

The products have different generation processes, but they all have a common denominator: everything is produced using microorganisms, which we feed with organic waste. We do not use chemical additives that aren’t 100% biodegradable and compatible with human consumption. Furthermore, the final products are also biodegradable; if you throw them on the ground, they disappear in six months. It’s fantastic: the soil’s microorganisms eat them up, plants absorb them… there is no waste.

“Our goal is to generate zero waste: 100% of what comes out is the product”

What biomaterials have you created?

One of our current lines is highly focused on food packaging. We have a contract with a multinational that works in cardboard packaging. The problem is that now many packages combine cardboard and plastic, and no one bothers to separate them, making them non-recyclable. One of the current alternatives is bio-based plastic like PLA, which comes from lactic acid generated by microorganisms. However, it’s not biodegradable; it’s compostable in industrial conditions. But if you throw a PLA tray on the ground, it stays there.

We have developed materials with a chemical composition exactly like paper, essentially cellulose, but with properties identical to plastic. They are transparent, flexible, and waterproof; when you look at it, you’d think “this is a piece of plastic.” But it goes to the blue bin, the one for paper, and if you throw it on the ground, it disappears in a few months and leaves zero waste.

What could your products be used for?

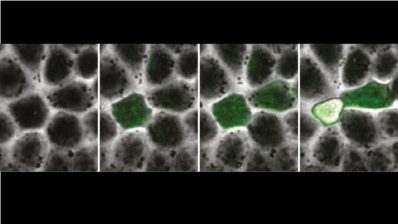

Currently, we are using microorganisms as the active ingredient in different products. In agriculture, we are using them as a replacement for chemical fertilizers. We’ve done tests with wheat, and the results are very good, doubling the yield.

Another product is focused on fish farms. We are currently doing trials in controlled environments, and fish mortality has decreased by over 70%, meaning better welfare for the animals and increased yields.

We also have a third product with unexpectedly good results. It’s very preliminary, but we’ve seen it helps olive trees recover from Xylella fastidiosa, a bacteria that infects them.

What are you focused on now?

It may not be glamorous from a scientific standpoint, but it is absolutely essential from a market perspective: industrial scalability. Production is expensive, and few industries worldwide focus on this, meaning large quantities are needed to meet market demands.

How many people are there in BIOM? Has the team changed much from the beginning?

We’re a small team. We’ve had more people, depending on projects. Currently, we have 3 people in R&D and 3 in business development.

The team hasn’t changed much until now. We’ve had additions, such as an industrial doctorate who then went on to do a postdoc; but the core has remained stable, which is important for stability.

What are the future challenges?

The first challenge is to survive financially. Unlike academic research, in a company, there’s pressure to sustain yourself, especially in the early phases, like the one we’re in. You might have a great technological development, but bringing this to market will consume time, which translates into money. If you can’t support yourself during that time, even if the product is excellent, you’ll die along the way. We’re in that stage now.

The second goal is to complete product validation. Right now it seems everything works well, but we have to be very sure it does. And this takes time, especially in fields involving industrial production or in the case of olive trees with an annual harvest cycle, which adds a layer of difficulty.

“We want to be an idea-generating machine; for the profits of one product to feed the development of others that have a positive impact on society.”

Javier Macías (UPF, BIOM)

How would you like to see BIOM in five years?

I’d like to see BIOM as a company that is profitable and therefore self-sustaining, but above all, we want to be an idea-generating machine. The goal isn’t just to create something and then keep billing and billing; instead, that revenue should be reinvested to develop other products that do something impactful.