The Covid-19 pandemic has done many things, but one of them has been to revolutionize scientific publication. Not only the number of publications (at least on that topic) rose exponentially, but preprints in particular experienced a sharp increase in the biomedical field, which was still cautious about the approach of posting results freely available before peer review.

But something else that Covid-19 has emphasized is the importance of rigor and integrity in the communication of research findings. This has of course been a long-term aim of the scientific community, and one that has led to lengthy discussions, but it is now as timely (or more) than ever.

So, how to reconcile both things?

How to be sure we communicate thoroughly and fast, but also rigorously?

This year’s ‘Peer Review Week’, celebrated from the 19th to 23rd of September, focused precisely on the relationship between peer review and research integrity. This annual event discusses issues around ‘peer review’, the current quality control mechanism by other scientists that papers published at reputable journals have to undergo. And this year, under the title “Research Integrity: Creating and Supporting Trust in Research”, it aims to discuss how peer review can support open science, reproducibility and research integrity.

Which was precisely the topic of the seminar on publication ethics that took place at the PRBB last September 7, a hybrid event you can see below, organised by the park’s Good Scientific Practice group – formed by members of all centres to share good practices and raise awareness about research integrity.

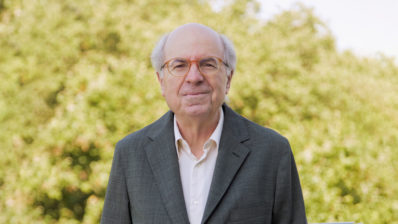

The speaker, Iratxe Puebla, is the Director of Strategic Initiatives & Community at ASAPbio, a small non-profit with a vision to make communication in the life science faster and more transparent, by supporting the productive use of preprints and openness and transparency in peer review.

Major integrity issues in publications

The talk started setting the scene with the so-called reproducibility crisis: number of retractions on the rise (although they are still a small percentage of all published papers) and several attempts to replicate experiments achieving <50% success. Although whether there is really a crisis is debatable, what’s clear is that the current perverse incentives, which focus on evaluation through metrics, may compromise reproducibility by encouraging being “first versus being rigorous”.

Puebla, who is also a Facilitation & Integrity Officer at the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), shared some of the topics most discussed in COPE forums – so, what journals and editors most commonly find – such as authorship conflicts, allegations of misconduct or post-publication discussions and corrections.

“I find it striking that in the XXI century, with all the technology we have, it’s still very tricky for readers to respond to published articles and for journals to provide a streamlined process that allows reanalysis, rebuttals, etc”.

Iratxe Puebla (ASAPbio)

The professionalization of misconduct

But according to the expert editor, more than this small-scale, individual cases, a worrying trend is the large-scale ‘professionalization’ of misconduct in publications.

- This includes predatory journals – open access journals that don’t operate a proper peer review and publish pretty much any paper, as long as the author pays a fee.

- A newer player are Paper mills – companies that create fake papers, send them to several journals, and if and when they are accepted for publication, they offer authorship to interested researchers – for a fee that depends on the ranking of the journal, the position of the author in the authorship byline, etc. According to a COPE and STM (International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers) report, between 2% and 46% of submissions to a range of journals may be from paper mills.

- A third large-scale issue is the manipulation of the peer review process, with authors tricking the system to suggest themselves (or others they collude with) as reviewers of their own paper, through with fake emails. “This is not trivial; I’ve seen it happen hundreds of times”, says Iratxe.

System level solutions

These system level large-scale problems can only be solved with collaboration from all stakeholders. Puebla mentioned some examples:

- Think, Check, Submit: develops resources for scientists to look for reputable journals before submitting and identify signs of low standard journals.

- Greater awareness and resources for editors – COPE gives tools to editors and practical guidance for the handling of publication ethics concerns.

- Collaboration between stakeholders: STM is trying to get all publishers to work together through the STM Integrity Hub to create technology to deal with image manipulations, among others integrity threats. And COPE is now accepting membership of institutions, and not only publishers, to try and bring different stakeholders to work together.

Too little… too late?

But even if all stakeholders get together to solve these breaches of publication ethics, isn’t it too late to wait until the paper is published?

“The most pervasive issues are not intentional, but related to the current publication practices”, says Puebla. For example, there are many reproducibility problems that arise because of the lack of data. “Less than 10 years ago, I was in PLOS when we introduced the policy to include the data in research publications – and there was a lot of push back!”, she adds. So, even if nowadays we expect to see the data underpinning an article, for many of the published papers in history, most of the data is not available.

Journals are on the mend, and most of them currently require authors to provide the raw data and material, including original Western blots or gels. “In my experience, the majority of issues with images are not necessarily with an intention to deceive, but rather that the authors went too far with the beautification process, to try and make it clearer”, says the ex-editor. Journals are also implementing the CRediT taxonomy, which describes 14 types of author contributions, to make more visible different types of contributions – and hopefully prevent some of the authorship conflicts that may arise.

Open Science to the rescue

But the ultimate solution, Puebla offered, is to leverage Open Science: opening up the whole research process, from the design and methodology, through all the data and code, to the peer review (the reports and the names of the reviewers) and the results. After all, open science is about being more transparent, and more transparency means more accountability, which increases society’s trust in science. Also, at the core of open science is being more collaborative with others. A win-win solution that institutions like UNESCO and even the White House Office of Science and Technology and Policy are embracing.

Open science may seem a daunting task, but Puebla, who is also a member of the Board of Directors for the data repository Dryad and co-lead of the FORCE11-COPE Research Data Publishing Ethics Working Group, offered a short checklist for those interested:

- Pre-registration – to post or publish your study plan before you even start, so you hold yourself accountable.

- Data sharing – and recognition of datasets as research outputs in their own right.

- Preprints (copies of research manuscripts uploaded by researchers themselves into a platform, without peer review). “The preprint is available within days – before a probably useful but very lengthy review process – and provides an opportunity to other researchers to comment on the results, to use them for their own research… and to the authors to address errors before journal publication thanks to the open feedback”, mentioned the speaker.

“Open science can give us a lot of tools to address the most pervasive issues of publication ethics”

Iratxe Puebla

Another important characteristic of preprints that Puebla highlighted is that they are free to post and to access, which can help address the potential inequalities we may see within open access and some models that rely on article processing charges. “And many journals now accept manuscripts that have been posted as preprints”, she added.

Open Science may not be the panacea, but it is definitely a promising avenue, and it is here to stay. There are still many issues to be addressed, as pointed out by the audience during question time, like confidentiality when sharing data, or the need to protect young researchers who act as reviewers. But perhaps the Achilles’ heel for Open Science, and what needs to be solved for it to really take of, is the link to evaluation. As concluded by Puebla, “If we value rigor and open science it has to become part of the reward system, and not be something researchers do for the greater good”.