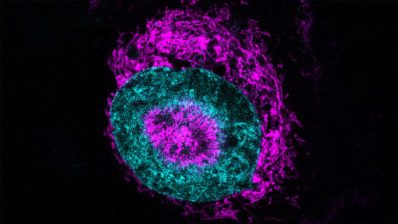

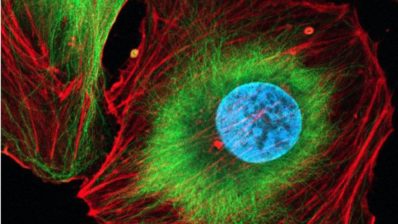

The Human Cell Atlas (HCA) is an initiative that aims to create a map of all the cells of the human body, see how they interact with each other and how they change from birth to old age. The project, which was launched in 2016, involves almost two thousand institutions and four thousand researchers from over 100 countries. The creation of this atlas is a considerable advance for reaching personalised medicine.

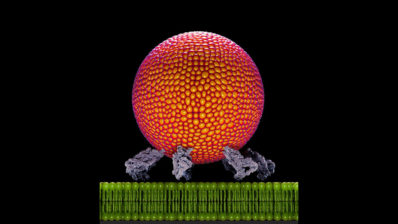

The consortium is formed by eighteen networks that study the different tissues and organs as well as the development stages and the genetic diversity. So far, over 100 million cells from over ten thousand patients have been collected. These have been analysed combining state-of-the-art techniques as genetic single-cell and bioinformatics.

Among other successes, the project has discovered a new cell in the intestine that could be responsible for the inflammation in Crohn’s disease. All the discoveries have been published in over 40 scientific papers in different Nature’s journals during this autumn.

Genomic Data: balancing the maximum benefit with an ethical use

It is not an easy task to coordinate a group so big and so diverse of people. Moreover, the ethical repercussions of working with so much human data are astronomical.

That is why from the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), Roderic Guigó co-chairs the consortium‘s ethics working group along with Bartha Knoppers, director of the Centre of Genomics and Policy at McGuill University and a worldwide authority on ethical topics.

Issues such as privacy of the genetic data, fair access and ethical use of the data are essential in a global project like this. It can get more complicated when dealing with data from minors or postmortem samples that require a special look in ethical terms. Also, there’s the fact that ethical and legal considerations as well as patients’ rights change between countries.

“Considering that they are human samples that produce genomic sequences and, therefore, can be identified, we need to balance the maximisation benefit from the data while guaranteeing its privacy in accordance with the legal frame of each country”

Roderic Guigó (CRG)

That is why the ethics working group has developed a toolkit that scientists of the HCA can use to guarantee the patients’ rights and to comply with the legislations at all times. This includes informed consent forms, tips about sharing data and others, as well as an address for contact in case of ethical questions within the project.

“The aim of the Ethics Working Group of the HCA is to develop general recommendations that could be adjusted to the special features of each country to maximise the benefit of the data; that is, to make them as available as possible while, at the same time, guaranteeing their privacy within the legal framework of a country” says Guigó. This balance between the advancement of science and the protection of the person’s privacy is not easy. “In my opinion, emphasising on the privacy can sometimes be costly and slow down the scientific progress. I believe that intermediate solutions such as EGA (European Genome-Phenome Archive), in which access is controlled, can be good alternatives”, accepts Guigó.

A project that wants to be from and for all humankind

The commitment is that everybody would benefit from the Human Cell Atlas research, helping humankind move forward to a better world. “Having diversity on the samples so they are representative is a priority within the HCA and other genomic projects, taking into account that currently omic data come mostly from samples from individuals with an European origin”, says Guigó.

He adds. “Even so, it is not only important that the data represent all human populations, but that these populations feel they are part of the scientific endeavour. That is, we need to obtain omic data from individuals from India o Peru, but also that Indian/Peruvian scientists carry out (and even lead) the research process, gathering biologic material, sequencing and doing the analysis. It is not correct that the samples’ donors are from diverse origin, but all the rest is done in countries of the global North.”

“Currently, omic data are predominantly of European origin. It is necessary for all human populations to be represented, but also that they participate in the research process and even lead it”

Roderic Guigó (CRG)

Keeping in line with the idea of “being for everybody”, most of the HCA results are either free to access through the HCA or accessible through the controlled access of the EGA or the dbGAP, its American equivalent.

The ethics groups hopes that their work can be a benchmark for future big consortium projects in which the transparency and the patients’ dignity will be at the centre of the initiatives.

This article has been written in collaboration with María Pin Nó, a student of the Master in Scientific, Medical and Environmental Communication from the Barcelona School of Management of Universitat Pompeu Fabra.