Genomics has the potential to revolutionize medicine as we currently know it. For this to become a reality, it is essential to share large-scale genomic data among research staff, doctors and, above all, patients and volunteers from around the world. Infrastructure and tools are needed to store this data in the long term and distribute it with the necessary quality, security and confidentiality conditions.

EGA (European Genome-Phenome Archive) is one of these repositories, managed collaboratively by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI), in Hixton, Cambridge, UK, and by the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), in the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB), in Barcelona. EGA is the database with the most studies in the world; it currently contains data from more than 1 million people and more than 2000 studies around the world.

On December 10, an event took place in Madrid aimed at hospitals, doctors and research centres to discuss the impact of genomic data on health, and EGA’s role in this.

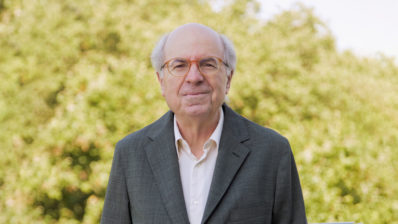

We talked to Arcadi Navarro, ICREA researcher at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) and director of the EGA team in Barcelona.

What is EGA?

We could say that it is a repository of genomic and phenotypic data… But, in reality, it is much more than that. It is a custodian, a distributor but, above all, a promoter and accelerator of research worldwide.

It emerged from a worldwide need to combine two fundamental human rights; the right of sharing genomic data, in order to help improve knowledge and health, and the right of privacy.

Let me explain myself: when you publish a study, you must deposit the data that you have used in a public repository — of which there are many —, and you have to do so while maintaining the anonymity of people who have donated that data. This is usually done by extracting or encoding identifiable information, such as name, age, etc. But, in the case of human genomic data, they cannot be anonymized because each genome is unique! Therefore, at the end of the year 2000, two very special repositories were created, one in the United States — the dbGAP — and one in Europe — the EGA.

“Genomic data cannot be anonymized because the genome is unique.”

And what is especial about them?

They keep data from scientific studies with the highest security, and distribute them worldwide — to legitimate scientists, from recognized institutions, and who accept the same conditions accepted by those who originally collected the data.

We could say EGA is like a global showcase of genomic studies. That is, the specific data of each study can only be obtained if you go through a Data Access Committees where you have to explain what you will use them for, etc. It is very regulated. But on the website you can see the metadata, that is, the description of everything there is; you can see that there are studies of diabetes or breast cancer and know what kind of studies they are (how big it is, where it has been carried out, etc.). Anyone can see everything there is and ask for what interests them.

Private companies as well?

Yes! In fact, private companies also provide data to the repository and they can use any data as long as they accept the original conditions of use, just like everyone else. If these conditions, for example, stipulate that the data cannot be used for profit, they cannot do so. But if it is allowed, they can do it, whether they are a company or a university!

What are the differences between the American and European repositories?

The dbGaP was created by the NIH, and every project funded by the NIH must deposit their data there. Once there, they are managed by the repository itself, so that the scientists who have generated the data ‘lose control’ of what is done with their data.

The EGA works differently, because it is at a European level and depends on many jurisdictions. Depositing the data is, for the moment, voluntary (although highly recommended by funding agencies!). And each institution that participates, that is, that provides data, can set up its own Data Access Committee and, therefore, they know in which part of the world they are using the data, how many times it has been distributed… It is a more cooperative model. And that is why some American studies not funded by the NIH, choose EGA instead of dbGaP to provide their data. That is why EGA is now the database with most studies in the world — although dbGaP probably contains data from more individuals, since the NIH funds very large studies.

“Each institution that provides data to EGA can set up its own Data Access Committee and control how many times and to whom it has been distributed”

Who manages EGA?

Initially, everything was managed from the EBI, in Hixton, Cambridge (UK). Since 2013 it is co-managed from there and from Barcelona. Here, the management of the EGA is carried out between the CRG, where Jordi Rambla and his wonderful team put the know-how and the administrative part, and the Barcelona Supercomputing Center (BSC), which puts the storage, management and distribution capacity.

And who pays for it?

For scientists, depositing and using all these data is free. But it has indeed a high cost. In England it is funded by the EBI itself, which is a unit of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory and, therefore, a European entity. Here, it is funded by Carlos III, La Caixa, the CRG, the BSC and competitive funding that we receive from the European Commission. For me, the EGA is the demonstration that when many different institutions agree to join in a collaborative action, it can have a huge global impact.

“The scientific community can deposite all these data in the EGA for free”

How is the use of data managed in relation to informed consent?

This is an interesting topic… An informed consent is a text that volunteers sign and that explains what can be done with these data. There are many types; from the most ‘restrictive’ one — when data can be used only for a specific study — to the most ‘open’ ones — when data can be used for any research project, and can even be made public. In between, there is all the variation you can imagine.

From my point of view, the most restrictive ones, which were the most used in the past, are a mistake since they mean that a lot of existing and already collected data is wasted… That is why there is an international movement, in which we participate, that aims for informed consents to be more recognizable among jurisdictions and, being totally respectful with the volunteer’s rights, benefit society as much as possible. And in this sense, together with the Broad Institute in the US and other institutions we are creating the first ontology of informed consents worldwide, the DUO (Data Use Ontology). We have taken many templates of different informed consents, and we have analyzed and cataloged them, and translated them into a machine-readable format.

What is the relationship between those who generate the data and those who use it later, at the level of collaborations, co-authorship…?

In the vast majority of cases, the original researchers do not appear in the subsequent study. But, sometimes, they might collaborate. Think about it: if you use very valuable data that has been generated by a highly competitive research group, you may well be interested in collaborating with them, since they are the ones who know the data best. So, using EGA data can bring about collaborations, and in the end it is beneficial both for those who use the data and for those who have deposited it.

In fact, in 2018 there were 18,000 articles that cited data stored in the EGA, and some of them were only possible thanks to the existence of the EGA, which aggregates and distributes the data. Without the EGA, these studies would have taken many more years or they simply could not have been done.

“Some research projects carried out nowadays thanks to the EGA would have never been done without this infrastructure”

What was the purpose of the event held in Madrid?

Main genomic data currently comes from large research studies in which personalized medicine relies. But the world is changing. It is estimated that by 2023, 80% of all genomic data will come from the clinical or healthcare world. And it is very important that these data are shared. Humankind cannot afford these data to be restricted to each research centre or hospital or to stay – once the diagnosis has been made – in a drawer or hard disk drive… Isolated and useless.

“By 2023, 80% of genomic data will come from the clinical or healthcare world. And it is very important that they are shared“

But sharing this data takes time and effort…

Of course, and that is why it is understandable that they often end up forgotten on a hard disk drive. If a doctor has such an important task as to deal with people’s health, the treatment with the patient and their well-being, these are their priorities! That is why EGA’s duty is to facilitate this part of publicizing and sharing the data they have, without having to spend many hours and resources. We want to do it as automatically as possible, so that it can be done in a short time. If we manage to give doctors the tools so that they can share these data effectively, the amount of information we would obtain to improve human health would be amazing.

“We want to give doctors the tools so they can share these data easily”

What is the message you want to send to the doctors collecting genomic data?

We are meeting with hospitals, and we have started with those located in Catalonia and Madrid, to see how we can work together on this. Our message is that we have this infrastructure and the know-how to move forward and make things easier. The aim of EGA is to generate the necessary tools so that all research centres and hospitals, both large and small, can easily share their data. And I believe that with everyone’s good intentions there will be more collaboration, better research and better diagnoses.

You can listen to a short part of the interview (in Catalan) here: