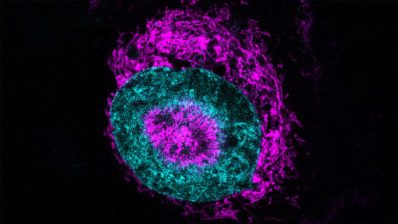

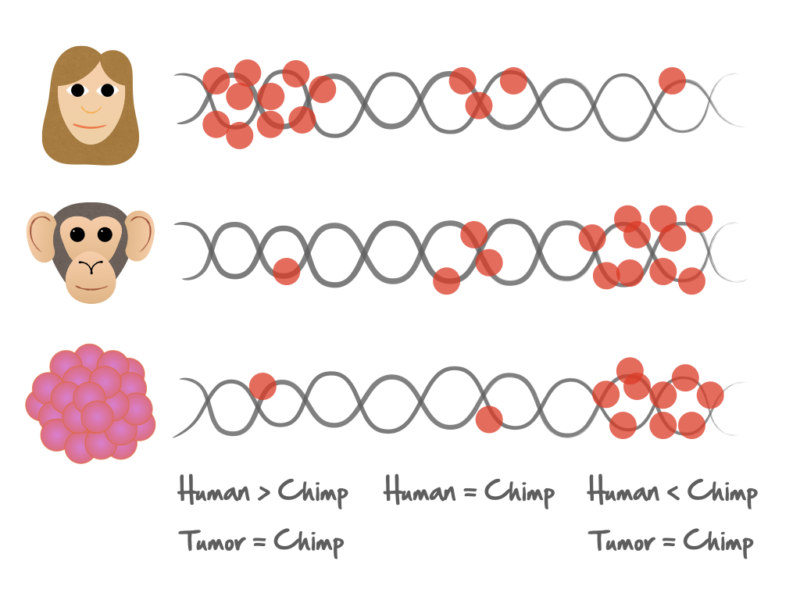

Thanks to the data from the project PanCancer, a research team from the Institute for Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF) has analyzed the regions of the genome that accumulate more mutations, comparing the genome of humans, chimpanzees and gorillas, as well as that of human cancer cells. Surprisingly, researchers have confirmed that the distribution of mutations in human tumours is more similar to that of healthy chimpanzees and gorillas than that of humans.

The reason?

It seems that the complex evolutionary history of humans — with several ‘bottlenecks’ where the human population has dramatically decreased — has “erased” these signs of mutations accumulation that we should have. In other words, in these phases of high human mortality, when a significant part of the population disappears, the general variability decreases. And this affects above all the regions where there was more variability (that is, more mutations). This has not happened in chimpanzees or gorillas, whose populations have not suffered from these bottlenecks.

And what does this imply?

These results, published in open access, would explain why mutations in tumor cells and mutations that normally occur in healthy humans are located in very different areas of the genome. It would not be, as previously believed, because of a special behavior of cancer cells, but due human evolutionary history. Thus, according to the first author of the study (led by Arcadi Navarro), Txema Heredia, to understand how mutations accumulate in human cells and better understand tumors, it would be more useful to look at how they accumulate in great apes rather than in humans.

Heredia-Genestar JM; Marquès-Bonet T; Juan D; Navarro A. Extreme differences between human germline and tumor mutation densities are driven by ancestral human-specific deviations. Nature Communications, May 2020. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-16296-4.