A project led by Arnau Sebé Pedrós at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) has shown the genetic and cellular mechanisms that explain how the stony coral (with a hard skeleton) Oculina patagonica is able to feed both on algae and without them, thus adapting to life in a high range of temperatures.

Native to the Mediterranean, this coral is generally fed by a symbiotic relationship with photosynthetic algae. But when temperatures rise beyond 290C, it expels the algae. However, unlike other corals, for which this is lethal, this coral can survive long enough to recover the algae when the waters cool in autumn.

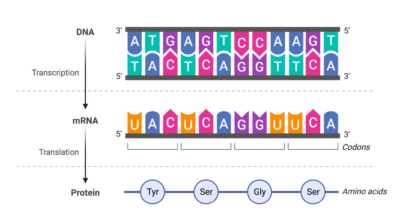

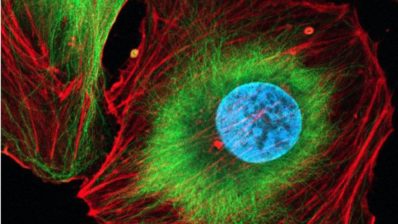

To understand this resilience at the molecular level, the researchers sequenced the genome of Oculina patagonica and analyzed tens of thousands of individual cells to determine which genes are activated when the marine animal does or does not contain symbiotic algae. In addition, they created cell atlases of two other tropical corals that depend entirely on algae, to make a direct comparison between species.

They found that when the algae disappear, Oculina readjusts its cellular programs and, among other things, expands its glandular and digestive cells so that it can capture and digest particles directly from the water.

“This ability to survive without algae is a huge advantage in a Mediterranean transformed by human activity, and one of the reasons why we decided to study this species,” explains Xavier Grau Bové, co-author of the study and postdoctoral researcher at the CRG.

Being a sea rather than an open ocean, the waters of the Mediterranean experience more abrupt variations in temperature, salinity and nutrient inputs. “The corals and other organisms that live here already face extreme fluctuations, so the Mediterranean offers us a kind of preview of how marine life might develop under accelerated climate change,” says Shani Levy, first author of the study.

Levy, S., Grau-Bové, X., Kim, I.V. et al. The evolution of facultative symbiosis in stony corals. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09623-6