The theory of evolution has always been predominantly gradualist, meaning it maintains that evolutionary changes happen smoothly, not suddenly. However, Darwin himself already noticed that there were unexplained evolutionary ‘jumps’. “He couldn’t find a satisfactory explanation within the theory of natural selection, which is why he didn’t mention this in his books; but this concern does appear in his notes,” says Sergi Valverde, a researcher at the Institute for Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF) and head of the Evolution of Networks Lab.

“The ‘saltationist’ view of evolution has always had a bad reputation. Given its apparent opposition to Darwinian theory, defending jumps has been associated with creationism or supernatural intervention, non-scientific views,” says his colleague Blai Vidiella, who currently works at CNRS, France.

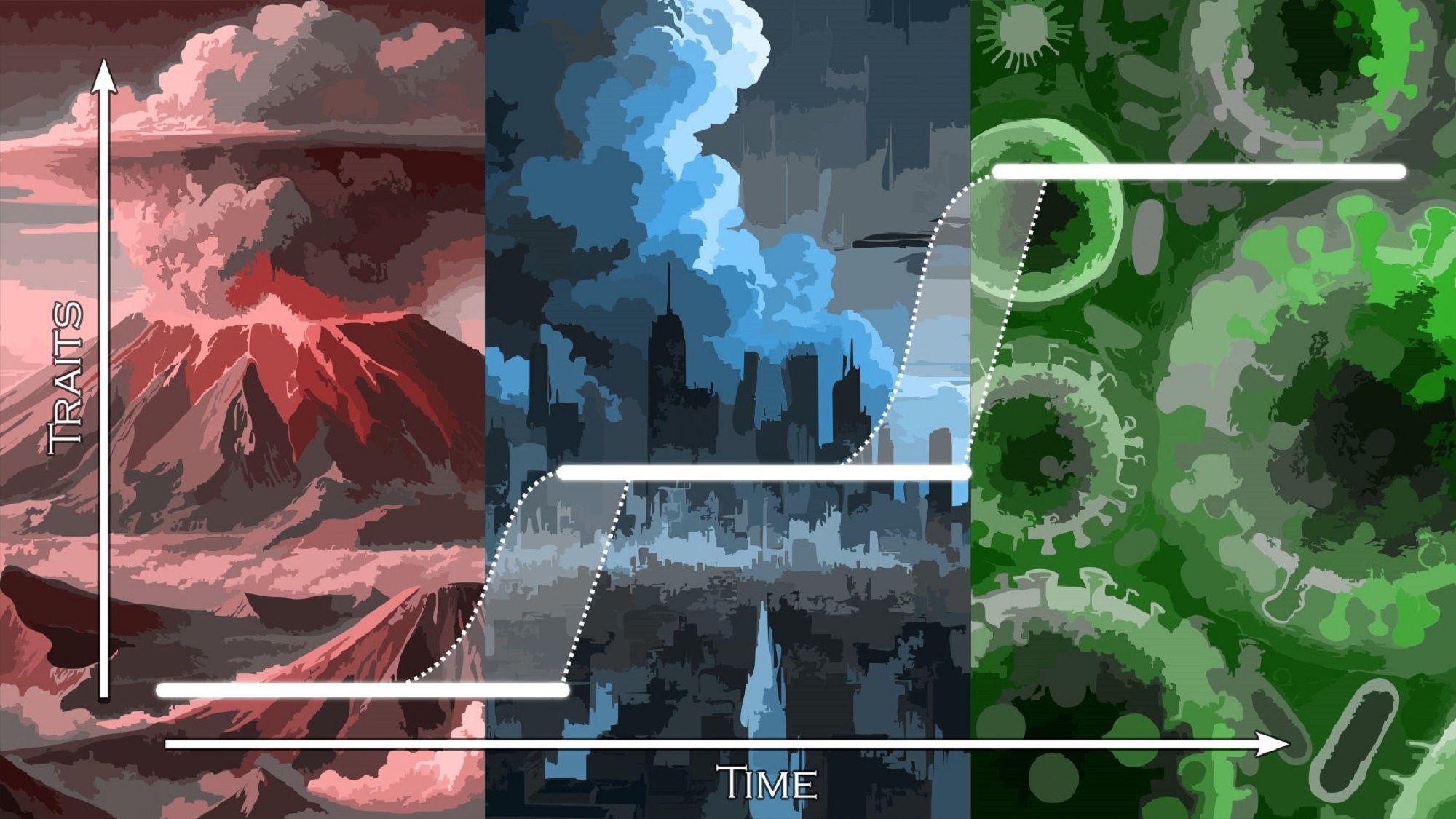

But things aren’t so clear-cut. Back in the 70s, paleobiologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould observed in the fossil record that there were periods where no changes in the morphology of a species were seen, followed by episodes of significant variation. To explain this pattern, they proposed the theory of punctuated equilibrium. This theory holds that in the morphological changes of a species, there are very long stable periods combined with others of very rapid change in a short time. Little did Eldredge and Gould know that 50 years later, the controversy sparked by their theory would still continue.

From punctuated equilibrium to punctuated evolution

Valverde’s group has recently delved into this theory, studying how the concept of punctuated evolution has varied over time and applying it to different fields. “In 2022, together with anthropologists from the United States, we found that cultural evolution can shift from gradual to punctuated due to internal mechanisms. After this discovery, we wanted to explore how this concept could have implications in other areas, such as anthropology or biology,” explains the group leader.

These studies have led them to propose a new term: ‘punctuated evolution’.

“The original term, ‘punctuated equilibrium,’ has historically been linked to sudden changes caused by a drastic external factor that alters the morphological pattern – for example, a meteorite that wipes out some species or a geographical barrier that permanently separates individuals of the same species, eventually making them two different ones,” explains Salva Duran Nebreda, a postdoc in the lab. “But this concept has led to major debates in the field because it is very restrictive.”

The IBE team observed that these changes could be caused not only by external effects but by the internal dynamics of normal evolution. Thus, what Valverde and his collaborators – including one of the original authors of the ‘punctuated equilibrium’ concept, Niles Eldredge – propose is to use the term ‘punctuated evolution,’ because the same evolutionary mechanism that leads to subtle changes can also lead to drastic ones, without the need for external effects.

The same evolutionary mechanism that leads to subtle changes can lead to drastic ones. This is what we have called punctuated evolution.

Sergi Valverde

Some examples in the biological realm would be the evolution of the coronavirus that causes Covid, where highly frequent variants seem to appear suddenly – but are actually the result of mutations, just like milder variants; or cancer, where a person may seem perfectly fine and appear to suddenly have advanced metastasis, when this is actually the result of an accumulation of mutations and changes in cells over time that are not visible – until they cross this threshold of metastasis.

Cultural evolution

When we talk about cultural evolution, until now it was assumed, as with punctuated equilibrium, that there is a drastic change (for example, the adoption of the personal computer by thousands of people) because suddenly someone, a genius like Steve Jobs, comes along, invents Apple, and revolutionizes the world. “But this myth of exceptionality is false”, asserts Valverde.

Cultural works or new technologies are the result of the accumulated work of many people over a long period of time. When there is ‘stability,’ it doesn’t mean that nothing is happening; people keep working, and those products that emerge and work well gets copied… We don’t see innovation in a sea of copies, but there is indeed innovation, the researchers say. When enough people adopt something new, when it’s good enough to capture the attention of many, that’s when we see innovation. “We call this point the ‘adoption barrier’, and we can mathematically calculate when it will be reached,” adds Vidiella. Continuing with the example of the personal computer: more than a decade before Steve Jobs began marketing the first prototype, they already had them at Xerox Parc, where many unknown people had worked for years and managed to create them. But they didn’t think they could be marketed.

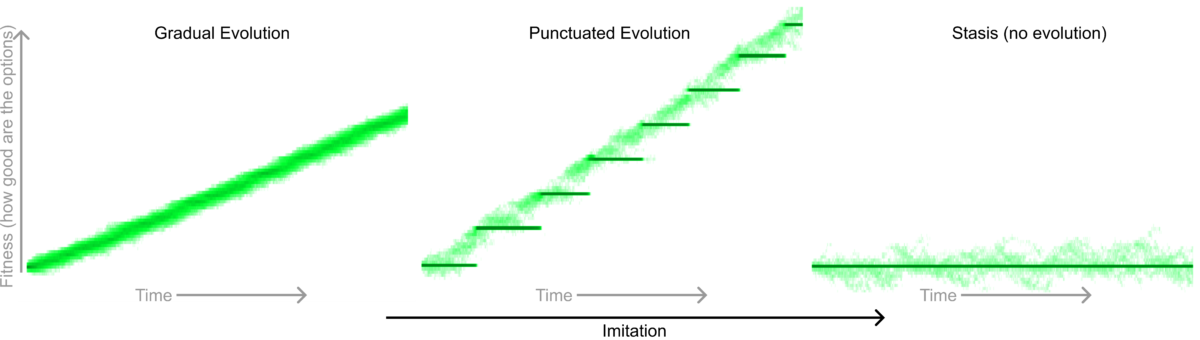

Thus, the mechanism by which cultural evolution can take giant leaps instead of gradual ones is social copying. “It can be very clearly understood in the sociological realm. You can have your own opinion about which party to vote for in an election, for example: you’ve informed yourself from different sources and chosen the option that seems best to you. Or you can go with the majority opinion, choosing what most of your community or the people around you choose,” explains Valverde. “If a lot of people choose this second option, a sudden, radical change in global opinion can be seen. But in reality, it’s a gradual change of some individuals who have managed to ‘pull’ the rest due to their popularity, for example, and standardize the opinion. There is this phenomenon, where it is more likely to choose the most chosen option”, he concludes.

The myth of exceptionality – that a genius comes and revolutionizes the world – is false. Cultural works or new technologies are the result of the accumulated work of many people over a long time. The great leaps in cultural evolution are due to social copying.

In this way, a greater or lesser weight of social choice versus individually thought-out choice is enough to see this shift from continuous evolution to punctuated evolution.

Social copying: danger or opportunity?

If we believe, as the group’s simulations suggest, that punctuated evolution can come from this social copying, what are the implications for the evolution of the decisions we make?

“It’s becoming easier and easier to homogenize opinions, especially in increasingly large communities. Social networks are a platform that allows social copying on an unimaginable scale. And unfortunately, this can slow us down in choosing the best options to face challenges like climate change because you may end up choosing the option that’s not the best, but the one that many others have chosen. Social media exploded as a tool to democratize and enable peace and social justice… but it’s been the opposite”, Valverde laments.

“Moreover, innovative ideas have always come from ‘odd’ people, those who go against social conformity. We have no way to foster innovation if only the opinions of the status quo are reinforced,” points out Vidiella.

“We can’t foster innovation if only the opinions of the status quo are reinforced”

Blai Vidiella, researcher at IBE

So, is social copying bad? “It’s like a yin-yang – it has allowed us to get where we are, it means we don’t have to reinvent the wheel all the time, and in that sense, it plays a key role. But if it is excessive, it can have negative effects if we copy what’s bad; and it can lead to misinformation, when what is recent and popular is prioritized over what is valid. It can also reduce innovation”, says Valverde. A danger that doesn’t seem imminent in science right now, according to a study by the same group that shows that scientific disruption (the abandonment of old ideas and the adoption of new ones) has actually increased over the last 20 years. The same study indicates it could increase even more thanks to artificial intelligence and its ability to retrieve disruptive or innovative studies that have gone unnoticed by the scientific community, for instance, because they’re from authors who aren’t recognized or ‘popular.’

Predicting evolution: learning from the past to improve the future

Returning to punctuated evolution and social copying, the group published a paper some time ago proposing how to predict the pace and mode of cultural evolution based on three parameters: social learning or copying, i.e., the tendency to imitate others; the access each individual has to truthful information; and the size of the population.

Thus, to predict whether a new technology will be adopted or to predict its evolution (as the group did with the invention of scissors), it would be necessary to assess what utility threshold it must overcome to be socially accepted, what level of transparency is required, and how many people would need to adopt it to trigger a global change.

In short, punctuated evolution (long periods of stability interspersed with rapid changes) can help explain the causes behind the sudden rise and fall not only of species but also of cultures and technologies. And perhaps more importantly, it can provide us with a framework to understand the implications of our decisions, better prepare ourselves, and influence the future of the planet and our own history.

Duran-Nebreda, S., Bentley, R. A., Vidiella, B., Spiridonov, A., Eldredge, N., O’Brien, M. J., & Valverde, S. (2024). On the multiscale dynamics of punctuated evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2024.05.003