It is estimated that by 2050 antimicrobial resistance will be the leading cause of mortality in the world. How have we reached this point, and what can be done?

Sara Soto is co-leader, along with Jordi Vila and Quique Bassat, of the research group “Bacterial Infections” at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal). Soto is also part of the center’s “Microbial Resistance” initiative.

This initiative recently published a Policy brief on the problem of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. We speak with Sara about it.

Sara, we’ve been hearing about bacterial resistance to antibiotics for a long time… are we reaching a critical point?

We are already at a critical limit! The other day I was talking with a doctor from the NGO Doctors Without Borders who told me she couldn’t treat a patient with anything… his infection was resistant to all known antibiotics. And it is a problem that affects us globally; with globalization, the transmission of these resistances between countries and even continents has increased greatly. But specifically in sub-Saharan Africa, not only are there very high rates of antibiotic resistance, but the antibiotics that reach them are not reliable, the doses are lower… there are even mafias that sell them cheaper but of lower quality. It is terrible.

And what is the cause of this resistance; misuse? the lack of development of new antimicrobials? the evolution of microbes?

The problem is a combination of factors, the main one being the overuse and misuse of antibiotics. People stop taking them too soon. If you need to take it for 8 days and every 8 hours, it’s not a random decision: it is because that is the necessary dose to prevent the antibiotic levels in the blood from dropping until the infection is over. It is the concentration needed to kill the bacteria, and a lower concentration or dose does not kill them, it makes them resistant!

In my opinion, a problem is that in primary care this is not explained enough, and the patient does not understand it. Some people even pressure doctors until they leave the consultation with a prescription for amoxicillin; otherwise, they don’t feel reassured!

But the problem of misuse is not just at the human level. Now it is prohibited, but for a long time in livestock farming, antibiotics have been given for animal growth, and also as prophylaxis, ‘just in case’ they get infected. Instead, sick animals should be isolated, but some people don’t have the space and instead ‘medicate’ all of them.

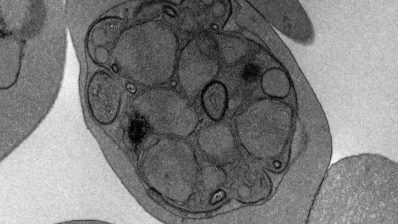

And then it all comes together in wastewater, where all the bacteria and antibiotic residues we use end up. And there, environmental bacteria that were not resistant to antibiotics swap genes; they take parts of the DNA from other bacteria that give them resistance! It is important not to forget this great transmission from humans to animals and the environment. Sometimes we have a very anthropocentric, clinical view, but it is all linked. That is why it is very important not to flush leftover medications down the toilet!

So, if microbes become resistant to the antibiotics we have, can’t we create new antibiotics?

Some new antibiotics are being developed, but few, and most are derivatives of those already available, so they are very similar in structure and quickly generate resistance as well – they are a patch, a band-aid. Not the solution.

And why are there so few, are we running out of sources from which antibiotics usually come?

Not at all; microalgae, for example, which I have worked on, are a great source of antimicrobials. The problem is that it is very difficult to identify and isolate them, it takes a long time. You might have to look at 10,000 molecules for only 1 effective one to come out, which in the end might turn out to be toxic… It takes about 2 billion euros to bring just one antimicrobial to market. And the economic incentives are low because they are short and cheap treatments. So pharmaceutical companies have somewhat left it aside…

It takes about 2 billion euros to bring just one antimicrobial to market, and there are no economic incentives for pharmaceutical companies.

Who should do it then?

It has to be the pharmaceutical industry because public research can’t afford it. Academic laboratories do research and reach preclinical stages, but from there on there is no funding…

But progress is being made with various economic agreements to make creating new antibiotics profitable for these companies. In the Subscription models being carried out in the UK, the government pays, for example, 1 million euros a year in exchange for having a certain number of functional antibiotics in stock; whether they are sold or not. They also have an initiative, the AMR Innovation UK Mission, to bring together medical and research personnel with pharmaceutical companies and other stakeholders to advance together against bacterial resistance.

And can’t synthetic antimicrobials be created?

Yes, that is the way. If you know where you want the antibiotic to go, with computational chemistry you can design it. Or you can create a chemical library, a ‘library’ of molecules, and start testing; from those that work, you study the structure and modify them further, etc. It is faster and more efficient, because with natural molecules you are working “blind”, and also the effective metabolites are mixed with many other things that you don’t know what they do. Also, they are produced in very small quantities – you have to do cloning in another organism or chemical synthesis. But we are in the same situation; funding is needed…

What do you do at the Microbial Resistance Initiative?

At ISGlobal, we have a policy department from where we lobby the government. In this initiative, we have a primary care project to raise awareness among doctors. We also work with children and adolescents through workshops, card games, educational talks, round tables, and even small research projects in schools or high schools.

You recently have published a policy brief. Who is it aimed at? Are you planning to publish more?

Yes, we have published the first one, a general one explaining how bacteria become resistant. We plan to publish one approximately every month; the next one will be on the concept I mentioned to you of One Health – that we are all interconnected (humans, animals, plants, the entire planet). Afterwards, other policy briefs – on low-income countries, new actions, alternatives, etc. – will follow.

The objective is to raise awareness among all audiences, including politicians, about this serious problem of antimicrobial resistance. The policy group plans to have meetings and lobby with governments and the EU.

In addition to greater regulation and monitoring, it is necessary to increase awareness at the medical, political, and general population levels: not to ask for antibiotics for everything, to complete the treatment, and to dispose of antibiotics at pharmacies.

What can be done?

We should have stricter regulations regarding antibiotics – in Spain, quite a lot is already being done at the human level and in their use in animals, for example, with the PRAN (national antibiotic resistance plan).

But we still need to reinforce many aspects such as surveillance and monitoring of resistances at the environmental level. And, above all, public awareness.

And on a personal level… what can the average person do?

For starters, don’t ask for antibiotics for everything! Complete the treatment and dispose of antibiotics at pharmacies: don’t keep leftovers for another occasion, or throw them in the trash or down the toilet.