Amelie Baud has had a clear idea of what she wanted to research since the third year of her PhD at Oxford University. At a conference, she was intrigued by a study in pigs showing that social partners influence the phenotype of each individual, that is, their physiological, morphological and behavioural characteristics. At the time, she had specialised in computational biology and her PhD focused on the genetic basis of phenotype.

Her passion for the idea of social influence, combined with the influence of the microbiome, has led her to work at the European Bioinformatics Institute in Cambridge, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Rome and the University of San Diego in California. In 2021 she joined the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) at the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB), attracted by the concentration of talent and resources at these institutions. She currently heads the CRG’s Social and host-microbiome systems laboratory.

Four PhD students and a research technician form his group. They are interested in how social interactions and the microbiome, especially gut bacteria, influence individual traits and health. “We don’t live in isolation. I think researchers have largely ignored this. We can’t study people in isolation, we have to at least take into account their social environment and their microbiome”, Baud explains.

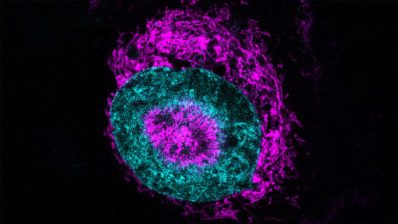

In their lab, they have discovered that the characteristics and behaviour of a rodent, its phenotype, is influenced by both its own gut microbiome and the rodents it lives with. They are currently investigating how this happens, using both computational and experimental studies.

“We don’t live in isolation. I think researchers have largely ignored this. We can’t study people in isolation, we have to at least take into account their social environment and their microbiome.”

Amelie Baud, CRG

It is not easy to analyse how one social partner can influence the characteristics and behaviour of another. You need an objective way of measuring these characteristics and this influence. That is why they use genetic studies, because they provide a good description of the characteristics of individuals and their microbiomes. Characterising their genes and the genes of their gut bacteria also helps to determine the direction of the interaction, that is, who influenced whom. For example, the study of genomes has shown that rodents living together share some of their gut bacteria.

In another recent study, in which they analysed 170 phenotypes related to behaviour and physiological and morphological characteristics in 1,812 mice, they identified 6 candidate genes involved in the indirect social influence, such as one gene involved in sleep patterns.

An interdisciplinary challenge

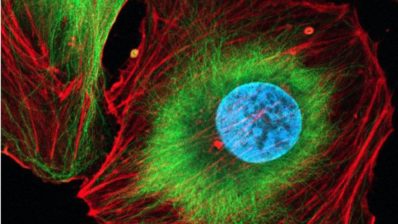

Baud’s laboratory combines computational methods with experimental studies on rodents. The use of animal models, which is very important in health research, makes it possible to validate results obtained thanks to computational studies. Experiments can help to better understand these results but can also raise new questions.

This interdisciplinary approach is challenging, but there is much to be gained by combining these two types of investigations. “I love it. Sometimes it is difficult because you are between two different scientific communities, where it is a challenge to communicate your science to non-experts. But also, by crossing scientific fields, you get to know areas of research where there is more to learn. So, I’m going to keep doing it,” she says.

“By crossing scientific fields, such as computational methods or animal experimentation, you get to know areas of research where there is more to learn.”

Amelie Baud, CRG

Very special rodents

The rodents in Baud’s lab are special because they are all unique individuals. Normally, biomedical research laboratories work with rodents that have the same genetic information – they are clones. But in this case, there is a need of individuals with unique genetic information, from different parents and with their own characteristics. This makes it possible to study how each individual is influenced by its social partner or by the bacteria in its gut.

The lab works with rats, but initially there was little data on the microbiome of these animals. Baud’s group has been cataloguing the bacteria in the gut of rats for years. Their results add to a very large database on the genotype and phenotype of these animals that is being compiled by a US consortium.

The consortium is led by Abraham Palmer from the University of San Diego, California. Baud worked in Palmer’s lab before joining the PRBB and continues to contribute to this database. All this information forms a rich catalogue of information on the physiology and behaviour of thousands of rats. Baud’s team and many other laboratories can use this tool to carry out computational studies.

Collaborations emerge at the PRBB

At the PRBB, Amelie Baud met Mireia Vallès-Colomer, who heads the Microbiome Research Group at the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences (MELIS-UPF), another centre in the park. Both have similar interests in the microbiome and use bioinformatics as a method of study.

“We have started to explore new areas of research together,” explains Baud. They will offer a joint PhD position led by the two researchers and funded by the new Joint Programme in Evolutionary Medical Genomics (EvoMG). The EvoMG programme involves three PRBB centres: CRG, MELIS-UPF and the Institute for Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF).

What the study of the microbiome and the social environment may bring to us

The study of the effects of the microbiome and the social environment on the health of individuals is a novel field in science. It is basic research that will help to understand not only the relationship between health and environment, but also other interactions between genome, phenotype and health.

This type of research uses a large amount of genetic, rodent and microbiome data. It also looks at a wide range of variables, such as weight, cholesterol, bone density, behaviours… It is therefore difficult to predict what discoveries it will bring us in the future, but these discoveries are likely to be applicable to many medical fields.

“By understanding how gut bacteria affect the host, we’ll hopefully be able to manipulate the microbiome for better health.”

Amelie Baud, CRG

Similar studies in humans are much more complex, but there are already some studies in this direction. This kind of basic knowledge may allow us to achieve very important advances in medicine in the future. “By understanding how gut bacteria affect the host, we’ll hopefully be able to manipulate this microbiome for better health”, Baud concludes.