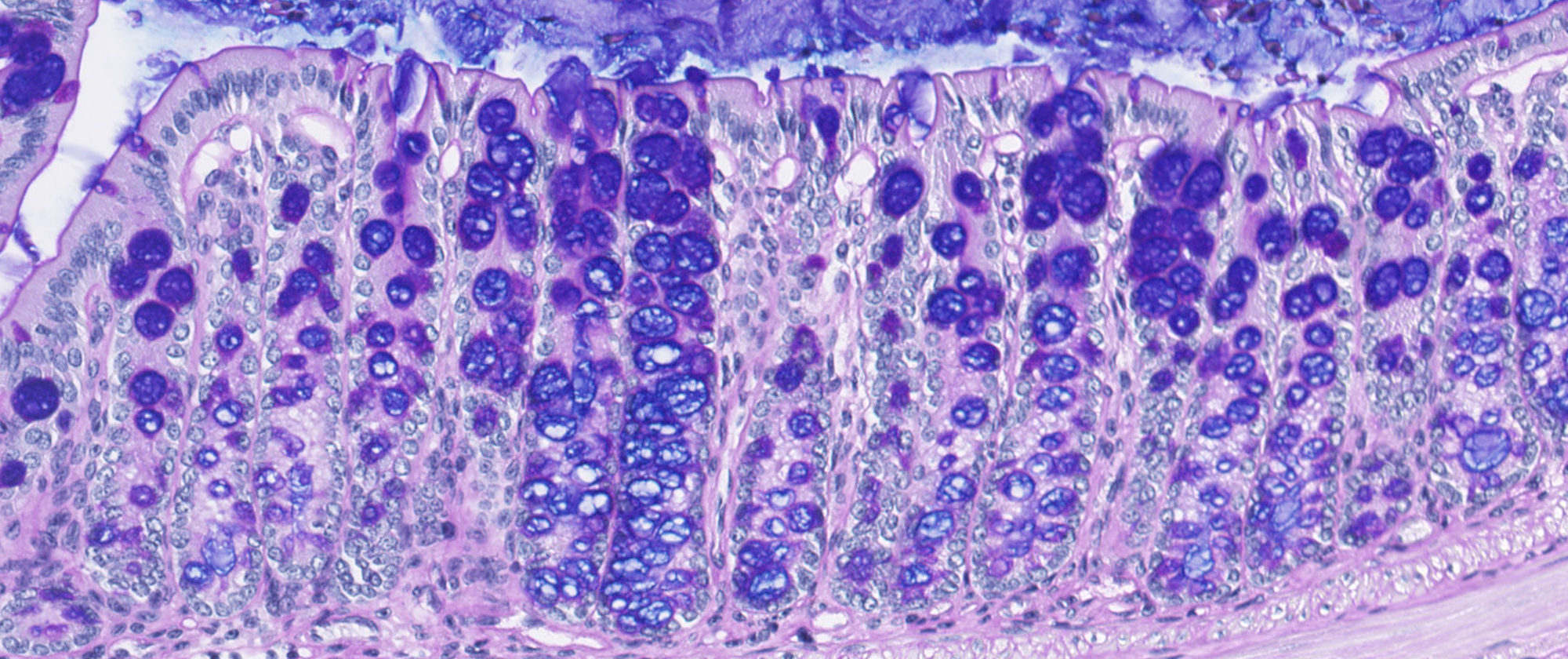

When we have a cold, our body seems capable of producing an endless quantity of mucus. Researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), in collaboration with scientists from the Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Pompeu Fabra University (DCEXS-UPF), have discovered the mechanism by which cells control how much mucin – the main macrocomponent of mucus – to produce according to their needs. Thus, caliciform cells, the mucus-secreting cells found in the mucous epithelium of the digestive system and respiratory tract, can produce large amounts of mucus in the presence of allergens or pathogens or release just the necessary amount constantly so as to preserve the mucous layer.

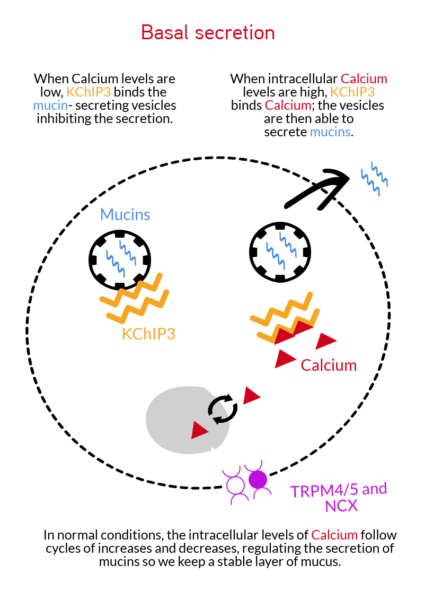

“There are two types of mucin secretion; the basal, to maintain the stable mucus layer, and the stimulated – via allergens or pathogens – where a great secretion is suddenly needed to protect the epithelium. It was known that this secretion is controlled by Calcium, but it was not known where that Calcium came from”, explains Gerard Cantero-Recasens, a post-doctoral researcher at the Vivek Malhotra laboratory at the CRG and the first author of the two articles that came out of this study.

The control mechanism that scientists have discovered is based on a double system of Calcium control:

- Two proteins, the TRPM4 ion channel and the NCX, located on the cells membrane, work together to control the Calcium intake into the cell.

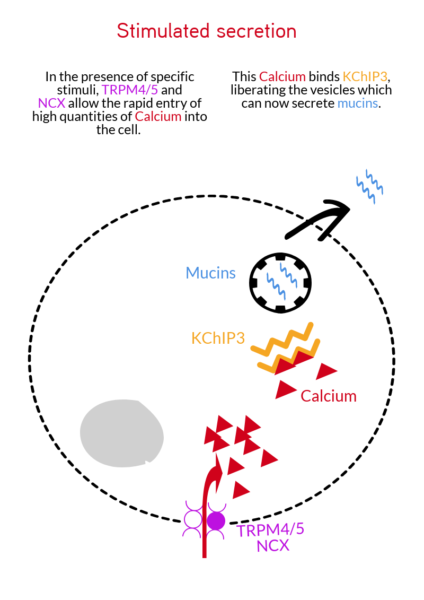

- A calcium sensor inside the cell, the KChIP3 protein, which controls the basal secretion of mucins to maintain an optimum layer of mucous to protect the epithelia. This sensor acts by inhibiting the excessive release of mucins, because in normal conditions it joins mucin-secreting vesicles, preventing the secretion. In response to regular Calcium internal peaks, KChIP3 releases secretory vesicles one-by-one, allowing a limited level of mucin secretion. But when TRPM4 and NCX let great quantities of Calcium into the cell, many of the internal sensors KChIP3 bind to Calcium, leaving many of the vesicles free at once, which can then secret the mucus. In fact, in an experiment with mice without the KChIP3 sensor, they had a more dense layer of mucous in the colon epithelium.

There are two types of mucin secretion; basal, to maintain the mucus layer that covers our epithelia, and the stimulated secrection, due to the presence of allergens or pathogens, which causes a lot of mucin to be secreted suddenly to protect the epithelium.

A long-lasting collaborative study

“The study began around 2013 with a genome screening where we identified 25 proteins involved in the secretion of mucin in colon cancer cells,” explains Cantero-Recasens.

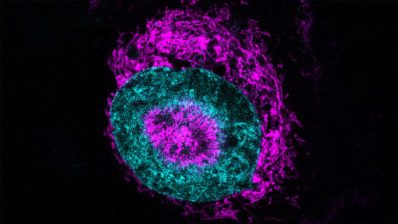

After selecting three of these proteins, they have studied them in cell cultures derived from healthy respiratory tracts, healthy colon, and colon with cystic fibrosis. “We have worked hard with the laboratory of Miguel Valverde here at the DCXES-UPF; we have used their microscopes as they have a system to measure intracellular calcium concentration”, says Cantero-Recasens.

Studying the different cell lines, the team discovered that the process of controlling the secretion of mucins – through TRPM4 and NCX – is the same in the respiratory tract and the colon.

The group is now collaborating with researchers from the Hospital Del Mar and the Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (IMIM) to identify if patients with respiratory and colon disorders have some genetic mutation in the mucins or in the proteins involved in their secretion.

They are also working to find chemical molecules that can control these pathways of mucin secretion.

Both approaches, genetics and chemistry, can become new ways of detecting and controlling the progression of illnesses where it there is too much or too little mucus, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Crohn’s disease or colorectal cancer.

In this video, the first author of articles, Gerard Cantero-Recasens, tells us first hand how they did this study.

Cantero-Recasens, G., Butnaru, C. M., Valverde, M. A., Naranjo, J. R., Brouwers, N., and Malhotra, V. (2018) KChIP3 coupled to Ca2+ oscillations exerts a tonic brake on baseline mucin release in the colon. Elife. 10.7554/eLife.39729

Cantero-Recasens, G., Butnaru, C. M., Brouwers, N., Mitrovic, S., Valverde, M. A., and Malhotra, V. (2018) Sodium channel TRPM4 and sodium/calcium exchangers (NCX) cooperate in the control of Ca2+-induced mucin secretion from goblet cells. J. Biol. Chem.10.1074/jbc.RA117.000848