In the last decade there has been a rapid increase in the publication and study of genomic data from ancient humans, going from 0 (in 2009) to more than 6,000 individuals sequenced today. This growth has been accompanied by debates about how to conduct ancient DNA research ethically.

Now, a diverse group of 64 specialists who are actively involved in ancient DNA research in 24 countries, has published an article in the journal Nature where they commit to following a set of ethical guidelines in these studies. This framework document has been translated into 23 languages.

We spoke with the expert paleogeneticist Carles Lalueza-Fox, principal investigator of the palaeogenomics laboratory at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF), who has participated in the development of this ethical framework for the study of ancient DNA and has been in charge of its translations into Spanish and Catalan.

What does this ethical framework consist of?

Basically we propose a series of points that the signatories commit to follow in our studies and that we believe are of global application, such as:

- complying with local administrative regulations

- preparing a detailed scientific plan prior to sampling

- minimizing the destruction of skeletal remains

- ensuring that the genetic data obtained are public – among other things, to allow a critical re-examination of scientific results

- involving other stakeholders, such as indigenous groups, in the custody of the data and the dissemination of the results

Where did the idea of creating this ethical framework come from?

A group of 64 researchers in ancient DNA, including experts in museum conservation, archeology, anthropology and ethics, met virtually on November 4 and 5, 2020 to discuss the need to establish a series of common ethical standards in the field.

At this meeting we presented case studies from various parts of the world to illustrate the variety of issues that exist related to consultation with indigenous communities and groups, and how they differ depending on the context.

“I explained that in some cases it was necessary to go beyond completing mere administrative formalities, especially in the case of vulnerable groups such as national minorities”

Carles Lalueza-Fox (IBE)

We need to keep in mind that the study of ancient DNA analyzes people who once lived and who should be respected. And it can also have great social and political repercussions on the ancestry of these individuals.

In the text you say that you have to comply with “local administrative regulations”; are these very different in each place?

The regulations are highly variable according to each country; in some countries with a highly developed bureaucracy, like ours, they can be very cumbersome. But as I have said, from our point of view, it is possible that these regulations are not enough and it is necessary to go further in some groups, especially in indigenous communities. Another important observation is that the existing regulations in the case of the “First People” or Native Americans in the United States – the most developed regulations so far – cannot be directly extrapolated to other countries and contexts.

Why was this framework necessary; have studies of the ancient DNA of human populations done so far been unequal or non-inclusive?

There has been criticism of some previous work, especially in the United States, where explicit consent has not been obtained from current communities identifying themselves as descendants of ancient populations, sometimes from thousands of years ago. It is a subject of great complexity, because this type of ancestry can be both cultural and genetic.

The issue of consent regarding ancient DNA is highly complex, because this type of ancestry can be both cultural and genetic.

For example, there is a recent case that is the identification of a descendant (great-grandson) of the Lakota leader Sitting Bull from the analysis of a lock of the hair of his great-grandfather, obtained by a white surgeon at his death – and therefore, without Sitting Bull‘s consent. In this specific case, there is a debate between the descendant individual and the tribe, and although the consent of the great-grandson has been obtained for the genetic analysis, that of the community has not been obtained.

And what are the peculiarities of studies with ancient DNA? Are those done in current populations, often also by European researchers in 3rd countries, also regulated?

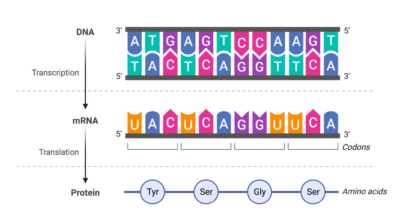

There are indeed regulations for genetic studies in current populations. But in the case of DNA from the past, two factors are added; one, that technologies now make it possible to obtain hundreds of genomes from all types of populations; and two, that the identification between people from thousands of years ago and their possible descendants is much more complex to discern.

Alpaslan-Roodenberg S, et. al. ‘Ethics of DNA research on human remains: five globally applicable guidelines‘, Nature , October 2021. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-04008-x.