David Cronenberg was closer to reality than he thought when he directed “The fly” back in 1986. Indeed, as different as we may seem physically, genetically speaking humans and (fruit) flies are very similar. The two species share nearly 70% of their genes. This similarity and its ease of manipulation make Drosophila melanogaster one of the favourite model organisms for researchers in fields as diverse as developmental biology, cell biology, neurobiology, behaviour, and evolution.

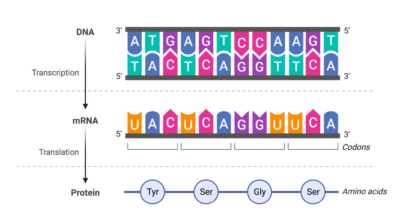

About 75% of the human genes known to be involved in diseases have a fly homologue, that is: a fly gene that has a very similar sequence to a human gene, and shares the same origin. Therefore flies are used to study diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. With this in mind, it’s easy to understand why the fruit fly was chosen to be the first multicellular organism to have its genome fully sequenced back in 2000.

Since then, studies on this 2.5mm insect have multiplied. In 1910 the first Drosophila research paper was published. A hundred years later, this little insect stars in more than 3000 research papers per year.

Some of the fly’s more valued features, that make it good for research, are:

- the low cost of set up, maintenance and experimentation

- their short life cycle

- their high fecundity

- their genome relatively simplicity (they have only 4 pairs of chromosomes, compared to 23 pairs in humans)

- the many tools available for their genetic manipulation

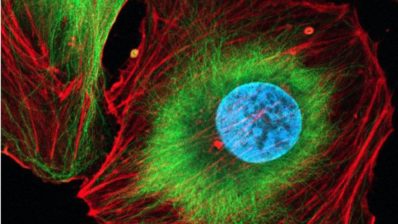

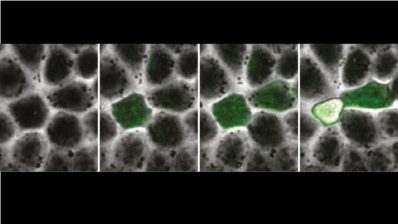

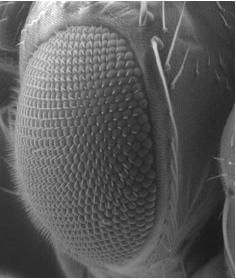

Flies are studied during all their developmental stages. Their eggs are relatively big and are often used for cell division studies. During the larval stages, the flies’ olfactory and chemosensory system is studied. And scientists look at the adult insect’s mating patterns, dissect their brains, and testis, and analyse their very complex eyes.

But fear not: despite the very real genetic similarity between flies and humans, a human-fly conversion is only possible, for now, in Cronenberg’s wild imagination.