TuMiCC, standing for Tumour microenvironment-derived factors in localized colon cancer, is a project in which the Hospital del Mar Research Institute (HMRIB) participates, in collaboration with VHIO and INCLIVA. It has been funded by the Spanish Association Against Cancer (AECC) with a million euros and is now in its fourth year of research.

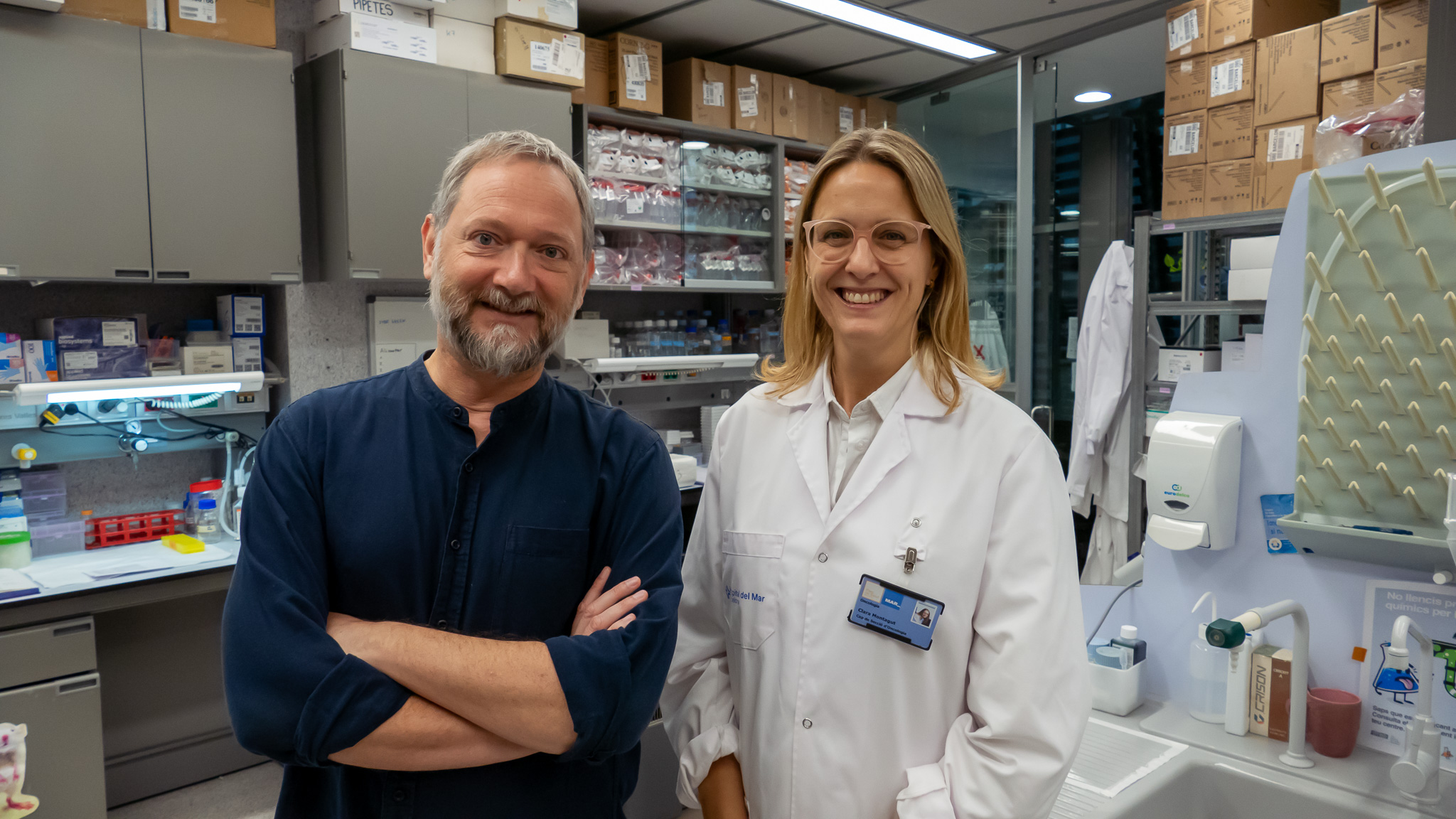

We talk with Alex Calon, head of the Translational Research in Tumor Microenvironment laboratory, and Clara Montagut, Head of the Medical Oncology Section at Hospital del Mar and head of the Colorectal Cancer Precision Medicine group, to learn about their findings and the future of this study.

The project’s goal is to understand how healthy cells in the tumor microenvironment interact with and aid the tumor cells.

Your research has focused on studying tumor microenvironment; what exactly is this?

Until a few years ago, cancer research was focused on the cancer cells, the ones causing the disease. But now we see that tumor cells need the surrounding cells, the ones in the microenvironment. Normal body cells accumulate around the tumor, which in themselves are not aggressive but are essential for cancer cells to sustain the tumor; this is the tumor microenvironment.

Cells in the tumor microenvironment provide structure, nutrients, and energy, and they also communicate with the tumor to make it more aggressive, proliferate, and metastasize—all of the functions of any cancer.

So, the goal of the study is to see how these non-cancerous cells help the tumor?

Yes, that’s what we want to understand: how the cells in the microenvironment interact and aid tumor cells. To do this, we use a translational and multidisciplinary approach, where medical staff and experts in biology, biostatistics, nursing, and pathology collaborate to understand the interactions between tumor and microenvironment and find new ways to attack the tumor, predict its development, and decide which treatment is best suited for each patient. Our research always starts with the patients, and we must work to ensure a return of what we do in the lab that can benefit them.

And what are you specifically studying?

We study colon cancer, which Alex has been working on for many years, and we have seen that the microenvironment is very relevant. We’re looking for different types of prognostic markers, markers of drug response and resistance, which can also be therapeutic targets.

“We conduct translational research. […] Our research always starts with patients, and we must work to ensure a return of what we do in the lab that can benefit them.”

Alex Calon (HMRIB)

How do you find these markers? What is your starting material?

We receive different types of samples. The markers are found in the tissue of the tumor and cells in the microenvironment. We also receive fresh tissue biopsies that are used for preclinical models. With the patient’s own tumor, we create 3D models and organoids to study the functionality of the microenvironment and how it interacts with the tumor.

We are also looking for markers in the patient’s blood, known as a liquid biopsy, as it’s a less invasive technique for the patient and can be repeated at different stages: before surgery, at the start of treatment, years later during follow-up… It’s very useful as it provides accurate information from each specific moment when the biopsy is taken, whereas a tissue biopsy only provides information from one point in time.

What have you found so far?

Our first finding was that chemotherapy reprograms the microenvironment. We used geological techniques to detect metals, specifically platinum, since oxaliplatin is a component of chemotherapy treatments for colon cancer. It turns out that some cells in the microenvironment concentrate the chemotherapy components much more than the tumor itself; this provides survival signals to neighboring cancer cells and enables the tumor to acquire resistance to oxaliplatin treatment. Here, we found a marker that can predict whether a patient will respond to chemotherapy.

It’s important to consider that chemotherapy is the foundation of colorectal cancer treatment, which is applied to all patients and only works for some. Some patients have initial resistance (primary resistance), while in others, it stops working long-term (acquired resistance). For years, attempts were made to find markers of response and resistance to chemotherapy in cancer cells. Suddenly, looking at the microenvironment, we found these predictive markers! In some tumors, they are already present at the start of treatment, while in others, the markers begin to be expressed when chemotherapy activates the microenvironment, i.e., an acquired resistance over time. This is a very important discovery, as in colon cancer, the only possible treatment is chemotherapy, and being able to predict its efficacy is highly relevant.

We are also developing an artificial intelligence (AI) model to predict patient relapse. We provide many images of the tumor and the microenvironment, some from patients with relapses and others without. The computer looks for differences that the human eye can’t perceive. So far, we are training it, but in the future, it could be a great tool for closer monitoring of patients who will relapse so we can do more to cure them.

“For years, we tried to find predictive response markers in cancer cells. Now, we’ve found them in the microenvironment cells.”

Clara Montagut (HMRIB)

What does it mean for you to be funded with 1 million euros by AECC?

We are very grateful because this grant is very competitive; very few people receive it. Knowing that the AECC provides this funding is a validation of what we’re doing; it means it’s significant and important. It reassures us because we see that our collaborations attract attention and that our ideas are interesting. It’s an amount of money that allows for relevant work that could benefit patients. It’s a privilege and an honor, but it’s also a huge responsibility to manage these resources in the best possible way to try to improve cancer treatment.

The project involves multiple research centers. What are the challenges and advantages of this collaborative way of working?

For us, it’s the only way to do real science with an impact. Cancer is too complex to provide valid answers if you stay doing your research alone, without stepping out of your comfort zone.

In terms of challenges, there are all kinds! You have to speak different languages, communicate with people from very heterogeneous areas of knowledge… We have worked with experts in medicine, but also in geology, biology, physics, chemistry… It takes a willingness to collaborate with different specialties and to get to speak the same language. But this is also a very beautiful part of research: bringing together such diverse people with the same goal and achieving what you cannot do alone. Plus, we always remember our ultimate goal, what we can offer the patient.

Here at the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB), we have a research center with highly skilled people and a hospital nearby. We have the responsibility to do science applied to the patient because we have the perfect place to do it.

“At the PRBB, we have a research center with very prepared and skilled people and a hospital nearby. We have the responsibility to do science applied to the patient because we have the perfect place to do it”

TuMiCC was a 3-year project, but it’s still active, right? What are you doing now?

The project was initially three years, and if we did well, it was extended to five. We did very well, presenting annual reports in which we fulfilled what we said we would do, met the established deadlines, expenses… We’re on track, and now we have two more years to finish obtaining results.

We are now in the fourth year, in which we will validate resistance markers. Additionally, in parallel, outside of this project, we are working on developing drugs which are very similar to current chemotherapy treatments but to which the microenvironment will not be resistant.