In November 2018, the scientific community kicked off one of the most ambitious projects of the moment with the birth of the Earth BioGenome Project (EBP). This project is a coordinated effort by researchers around the world with the ambition of sequencing the genome of the estimated 1.5 million eukaryotic species that inhabit the planet Earth.

Two years later, the Earth BioGenome Project has completed its pilot phase and large-scale production is now beginning; a milestone they hope to achieve thanks to the collaboration of several affiliated projects.

In the Catalan-speaking territory, we have the Catalan Initiative for the BioGenome of the Earth, one of these affiliated projects promoted by the Catalan Society of Biology, which, for the second consecutive year, finances the production of high quality genomes in the territory. And, in this second round, the Catalan Initiative of the EBP has awarded three projects to researchers at the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB).

The Earth BioGenome Project aims to sequence the genome of the estimated 1.5 million eukaryotic species that inhabit the planet.

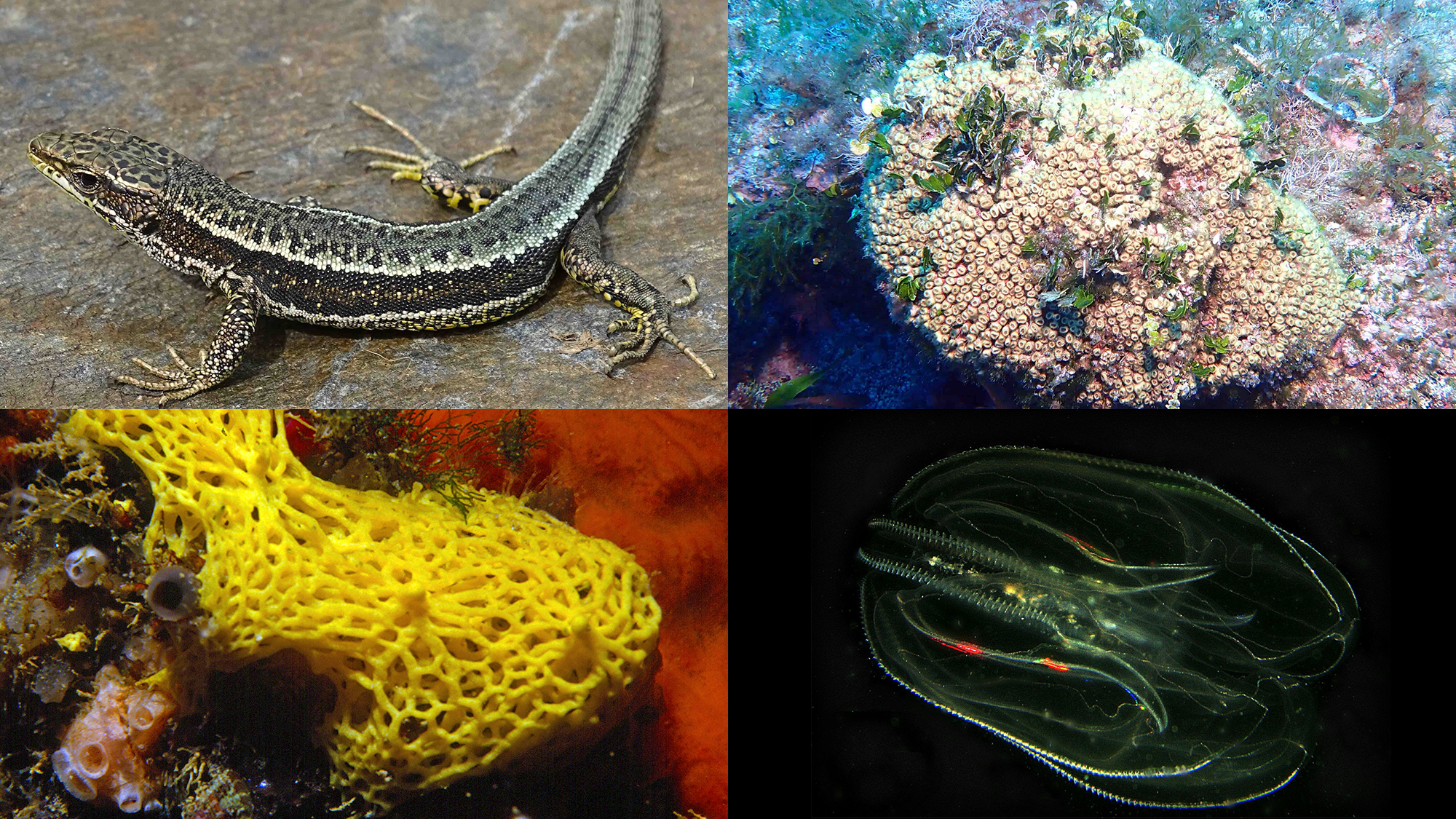

Reptiles at high altitude

The Pallars lizard (Iberolacerta aurelioi) is one of the eight lizards of the genus Iberolacerta that live in the Iberian Peninsula. Specifically, it can be found in high mountain screes, above 2000m, on a small mountain island in the eastern Pyrenees.

In Catalonia, this endangered species lives entirely in the Alt Pirineu Natural Park. And thanks to the conservation efforts of the fauna and flora of the park, this reptile is an emblematic species of the region. This is a robust lizard and has a life cycle marked by a long period of hibernation. Therefore, when May arrives, it eats, fattens, lays eggs and raises its young before hibernating again in late September.

But apart from its peculiar life cycle, the Pallars lizard has many similarities with the Aranese lizard (Iberolacerta aranica) and the Pyrenean lizard (Iberolacerta bonnali), from which it separated a few thousand years ago. And the desire to know the evolutionary relations between these three lizards has led the research group on systematics, biogeography and evolution of reptiles and amphibians of the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF), led by Salvador Carranza, to focus on this iconic reptile.

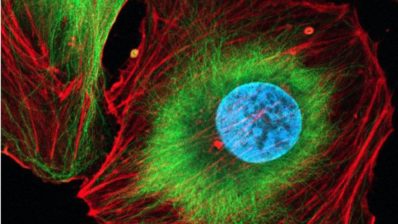

An out of place coral

Marine reefs, physical structures generated by living beings that protect the coastline, are places with a high and rich diversity. Although most marine reefs are made up of corals, in the Mediterranean most of them come from calcareous structures produced by some algae or sponges. However, on the coast of the Valencian Country, in the Columbretes Islands, we have a unique species: Cladocora caespitosa, which is the only coral that forms reefs on our shores.

But Cladocora has other features that make it special. Unlike most corals, it retains its symbiotic species inside. Therefore, when adverse environmental circumstances occur, such as a sudden rise in temperature, the symbionts cannot leave and die with the host.

These particularities catched the eye of the group of microbial ecology and evolution of the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF), led by Javier del Campo. In addition, Cladocora is an endangered species. That is why it is necessary to “have quality genomic information as soon as possible to generate useful tools for its conservation and preservation“, says del Campo.

The team he leads hopes that this genome will help them study the effect of climate change on the expression of this coral’s genes.

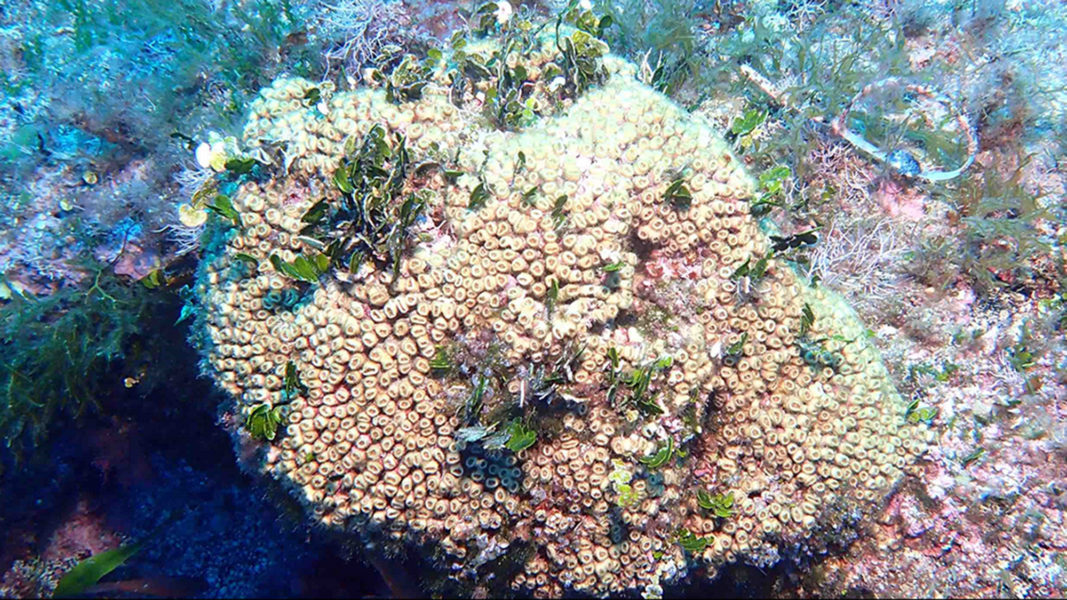

A rare sponge and an invading ctenophore

“Sponges are not very emblematic animals, and we often don’t have much information about them. And even less about limestone sponges!”. This is how Arnau Sebé-Pedrós, head of the single-cell genomics and evolution group at the Center for Genomic Regulation (CRG), presents Clarthrina clathrus, a calcareous sponge that inhabits the waters of the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

“The calcareous sponges and the rest of the sponges are as similar to each other as a Drosophila fly and a human,” explains Sebé-Padrós. Therefore, generating a quality Clarthrina genome will allow us to have a “proximity” reference genome of the lineage to study the cell types they have, such as their cellular and molecular biology and their evolution. To do this, they work with a biologist who specializes in sponges, Ana Riesgo, with whom they have gone to Blanes to collect the sponge.

Studying these unique organisms, which are evolutionarily removed from us, allows us to discover new metabolic pathways or molecules that we can take advantage of, such as the antitumor cytarabine, discovered in a marine sponge.

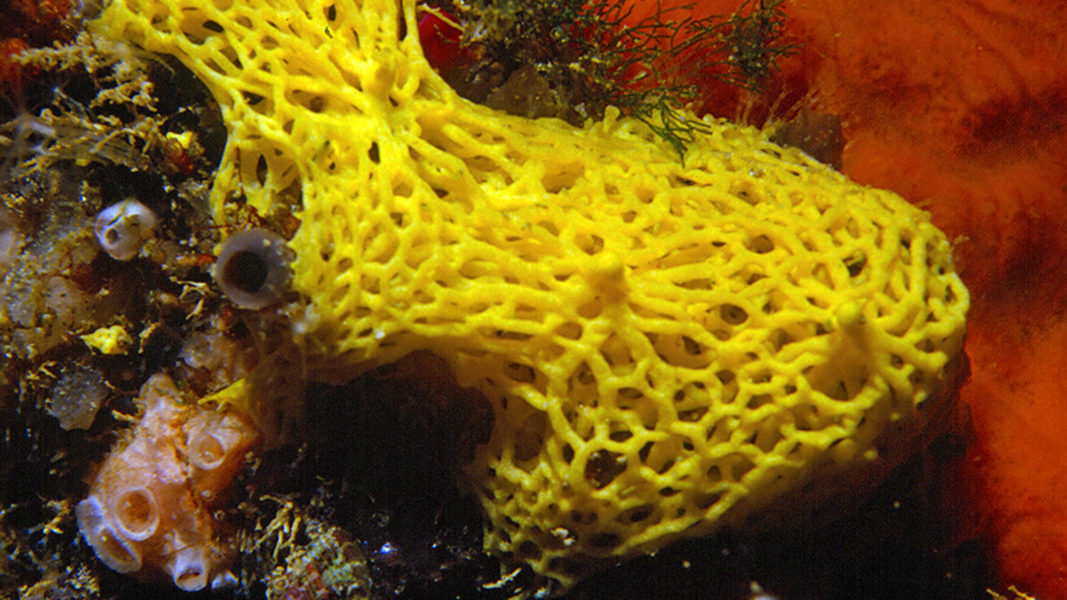

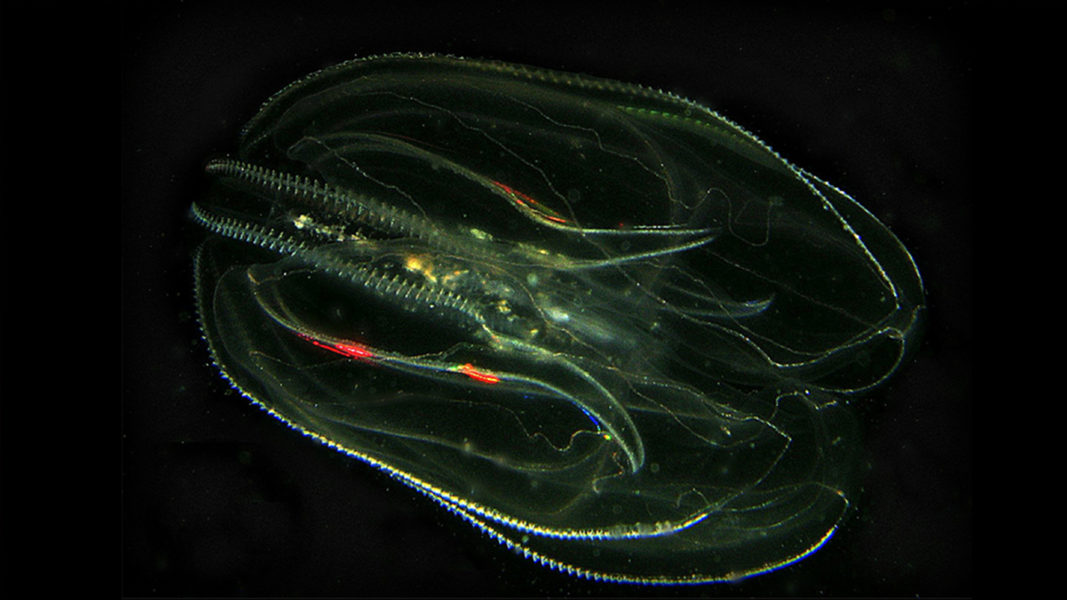

But Arnau also wants to sequence the genome of a very abundant species: the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi, an invasive species in the Mediterranean that grows disproportionately under certain conditions. “In the inland bays of the Ebre delta, when there is a sudden growth of Mnemiopsis leidyi, they say that there is ‘bad water’, because the water becomes dense”, explains Sebé-Padrós.

And the fact is that “ctenophores are like jellyfish, the more degraded the oceans, the better for them”. Studying its genome will explain its growth and help better understand animal development and the origin of neurons. That’s why Arnau wants to sequence its genome. Although it will not be the first time this is done, he hopes to improve the quality of the original genome that was sequenced 10 years ago.

Climate change, the great threat

Although it seems that these four species have nothing in common, the climate crisis is conditioning their presence in the environment. But the only species to benefit from it is Mnemiopsis leidyi.

In general, “climate change compromises the ideal conditions for the development of organisms,” says del Campo. And sessile marine species (which live attached to the seabed and cannot escape by swimming), such as corals and sponges, are more threatened. According to the biologist, “climate change causes a rise in water temperature but also promotes the proliferation of pathogens that cause emerging diseases. All in all, it alters the microbiome of marine organisms, compromises their immune system and ends up threatening species such as the Mediterranean mother-of-pearl, which has been in critical danger of extinction since 2016. “

Climate change is causing water temperatures to rise and the proliferation of emerging disease-causing pathogens.

Javier del Campo, principal investigator at the IBE.

In the high mountains, rising temperatures increase competition between species. The rock lizard (Podarcis muralis), which has a longer life cycle than the Pallars lizard and inhabits the lowlands of the Pyrenees, has expanded its distribution. “The last time we took samples, we saw a rock lizard at 2000m – where the Pallars species live – in areas where we had never seen it before,” explains Salvador Carranza. And although the two species do not yet compete, they are separated by just over 100m.

The Catalan BioGenoma project

Whether it’s to deal with the climate crisis or to understand the evolution of species, having new genomes will generate new knowledge. Which, according to del Campo, “has value, of course. Because knowledge that today we may think it’s not useful, might help us get out of a pandemic tomorrow“, he notes. This knowledge will be very valuable for professionals such as Salvador Carranza who, despite knowing the biology, ecology, taxonomy and physiology of some species, continues to have open questions.

In addition, the Catalan initiative has brought together two communities of researchers who did not always work together. “People from the natural history museum and the botanical institute are working together with people doing genomic studies, and new collaboration networks are being generated that are very worthwhile”, explains Arnau Sebé-Padrós.

People from the natural history museum meet with people who do genomic studies and worthwhile collaborations are set up.

Arnau Sebé-Padrós, group leader at the CRG.

This local initiative “focuses on endemic species in southern Europe that would not be studied by any global initiative,” emphasizes Sebé-Padrós. And it “positions southern Europe in world-class research projects“. On a smaller scale, according to the researcher, these studies equate the Catalan BioGenome project with ambitious projects such as the Darwin tree of life in the United Kingdom.